This article has been updated with more recent news on mask mandates.

Mask mandates have almost entirely vanished across the United States, after a Florida judge voided a federal requirement to cover faces while in transit. Major airlines and Amtrak swiftly discarded their mask rules. States, meanwhile, had been shedding their mask regulations all spring. Now, no state has a public mask rule. Guam, the final US territory to require masking indoors in public, may lift that requirement in early May.

Although cases have declined substantially, COVID transmission remains high in some areas of the country. Cases rose so sharply in Philadelphia that the city recently reinstituted an indoor mask requirement. Many epidemiologists have criticized the removal of mask precautions as premature, even if they agree that masking can be relaxed in the future.

You may be asking a now-familiar question: What’s your personal responsibility in the face of a societal problem? This is a story that has played out with booster shots, COVID testing, and relaxed isolation policies. The answers aren’t always satisfying: You can’t end the pandemic on your own, but you can make yourself safer.

No one around me is wearing a mask. Will wearing one protect me?

Short answer, yes.

Masks of all kinds appear to reduce someone’s chances of contracting COVID. Real-world experimental data has been hard to gather (it’s unethical to prevent people from wearing a mask for the sake of an experiment). But a study published recently by the CDC examined the habits of more than 1,800 Californians, and found that those who always wore at least a cloth mask indoors were 50 percent less likely to test positive for COVID than those who didn’t wear face coverings. That lines up with lab studies on mask efficacy, which find that most masks reduce the movement of particles both in and out. And the argument that masks are largely ineffective at slowing COVID transmission is the result of cherry-picked data, as Gothamist wrote in February.

That doesn’t mean all masks provide equal protection. The California study found that those who wore an N95 in all public indoor settings were 83 percent less likely to test positive—a massive improvement over cloth masks. Surgical masks sat in the middle.

“If you want to participate in daily life, and you feel you need to protect yourself more, you really need to upgrade your game and go to an N95 mask,” says Marcus Schabacker, president of ECRI, a nonprofit that independently evaluates medical equipment.

Part of the confusion over the benefits of masking comes from the fact that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention used to recommend any kind of mask, before emphasizing the benefits of N95s in January. Does that mean that cloth masks weren’t effective in the first place?

Not at all: The key thing to keep in mind is that cloth and surgical masks provide a societal benefit, even if they do less to reduce your personal risk. A surgical mask is fairly good at preventing you from spreading viral particles, even though it’s less effective than an N95 at keeping them out. A cloth mask is less effective than a surgical mask or respirator, but still contains some of the aerosols you exhale.

And that means that any kind of mask can be a useful public health tool, even if it doesn’t provide the absolute best protection for its wearer.

Think about it this way. Say a cloth mask reduces the chances of contracting COVID by 50 percent, as in the Californian study. COVID transmission will be slower, softening the blow to hospitals, and preventing many infections across a society. That’s a worthwhile goal. But there might still be some personal risk to you.

That’s why the CDC now recommends N95s or similar respirators for protecting yourself against infection. As long as these masks fit well, they filter out around 95 percent of incoming particles.

A person wearing a respirator can expect to be protected for about seven times as long as someone wearing a cloth mask, all other things being equal, according to an estimate published by ECRI. Another study from December 2021 found, based on particle modeling, that if a healthy person in an N95 spends 20 minutes right next to an infected person wearing a surgical mask, they have less than a 1 percent chance of catching COVID. If neither were masked, the healthy person would have a 90 percent chance of catching the virus.

N95 masks protect the wearer “even if the people you’re interacting with are wearing nothing and are infected,” says Schabacker. “That in combination with a certain amount of effectiveness of your antibodies, either from vaccination or from a natural infection, should help protect you in most situations, like mass transportation, a school room, shopping, at a Super Bowl game.”

Should I wear a mask around vulnerable people?

Masks are even better at preventing you from spreading COVID to others. If you have a loved one who is at high risk for severe disease, or a child who isn’t vaccinated yet, wearing a mask will absolutely make them safer.

The same rules of thumb from above hold true: While cloth masks reduce your risk of transmitting COVID, respirators come close to eliminating it.

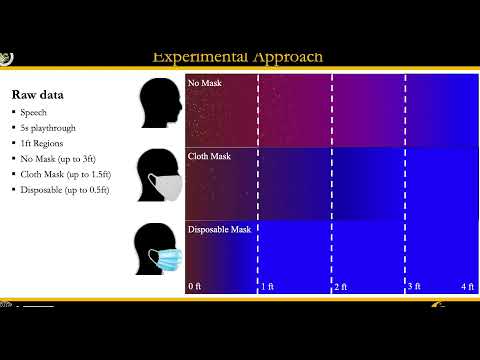

The clearest demonstration of that efficacy comes from a study published in January. Researchers brought test subjects into a lab, gave them a variety of face masks, and recorded them speaking and coughing in front of a camera normally used to study the movement of jet fuel.

(You can watch the results below.)

“What we found is that the propagation of aerosols and droplets in a cloth mask was on the order of like two feet for speech and 2.2 feet for a cough,” says Kareem Ahmed, senior author on the study, and an aerospace researcher at the University of Central Florida. “That’s still relatively large. If we’re speaking to each other, you’re most likely going to be within one to two feet.”

Surgical masks cut that down to about half a foot. The study didn’t even illustrate the effect of N95 respirators, Ahmed says, because there was nothing to see. Effectively no particles escaped.

What are the limitations of masking?

A mask works only if you actually wear it. Make sure it’s comfortable and fits well. You might have to try on a few different versions, though Schabacker notes that many drug stores now offer free N95s from the federal government.

Ahmed says that an easy way to test the mask’s fit is to see if your glasses fog up while wearing it—if so, you need to adjust the nose to form a seal. (We have more details on buying masks here.)

And make a point of wearing a mask in situations where it matters most. In a paper titled “COVID-19 false dichotomies,” published last summer, a team of public health researchers, virologists, and epidemiologists argued that policymakers should seek a middle ground between universal masking and no mask requirements at all. “Not all settings and activities allow mask wearing or confer the same risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection,” the team wrote.

The same principles hold true for individuals. When there’s a high risk of being close to infected people, wear a mask. In general, that means public indoor spaces, or tightly packed crowds outside. In a home, masks are most useful when there are visitors. That still holds true when everyone is vaccinated, because for the moment, the CDC lists the entire United States as an area of high transmission.

A mask is just one tool for reducing your chances of infection. It’s not a magic shield. The less time you spend in tight quarters with people outside your immediate family, the less work the mask needs to do.