We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

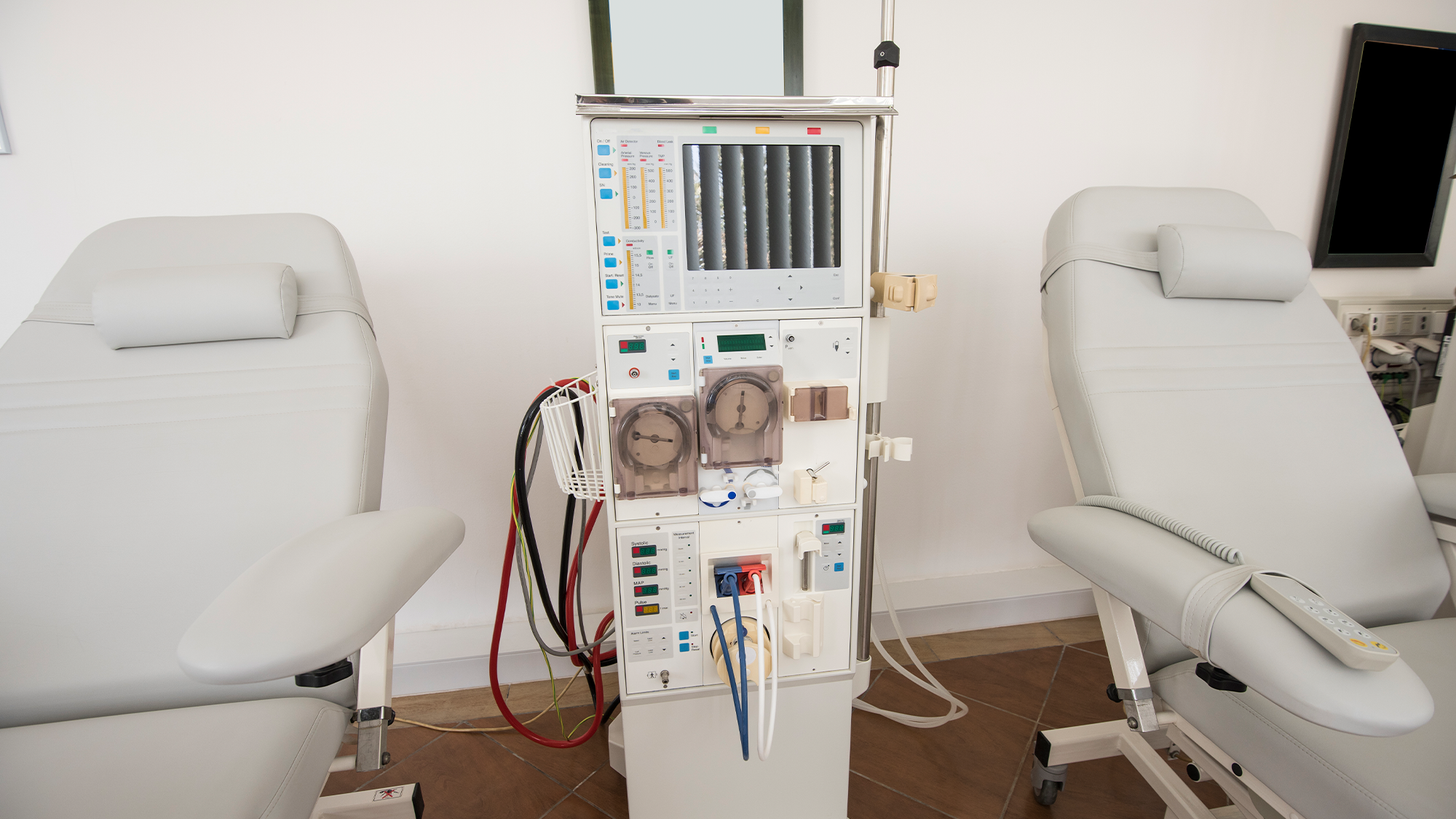

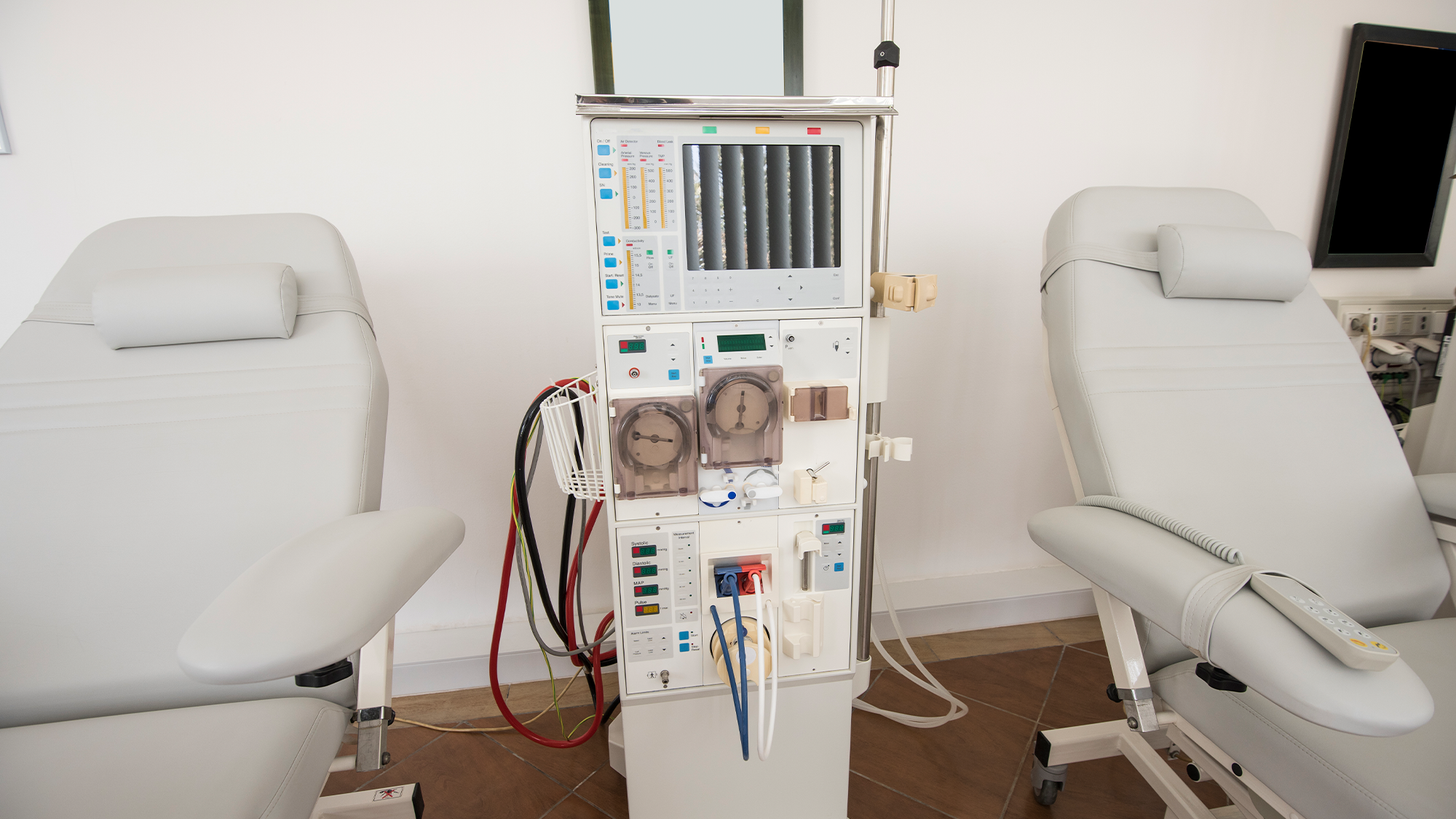

For patients experiencing conditions like kidney failure, treatments such as hemodialysis or dialysis can filter toxins from the blood when the kidneys can no longer keep a person healthy. It’s life saving, but it comes with the risk of dangerous staph infections in their blood, which can cause blood, skin, joint, and bone infections and pneumonia.

There are also some serious racial and economic discrepancies in the level of risk during dialysis treatments, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Vital Signs Report released on February 6. Hispanic, Latino, and non-Hispanic Black Americans, as well as patients with a low socioeconomic status experience a higher rate of infection.

The findings highlight well-documented healthcare inequities in the United States where race and socioeconomic status directly impacts health.

The report used data from 2017 to 2020 to pinpoint common patterns among patients who contracted bloodstream infections. It found that in 2020, roughly 14,800 bloodstream infections were reported and 34 percent of them were caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus)—the bacterium that causes staph infections. The procedure relies on needles and catheters to circulate a patient’s blood through a machine that cleans it.

[Related: These doctors are fighting to make the kidney-donor system less racist.]

“Germs like staph can get into the patient’s bloodstream via these access points,” said acting principal deputy director of the CDC Debra Houry, in a briefing on February 6. “These infections can be serious or deadly, and some are resistant to some of the most common antibiotics used to treat them.”

Patients undergoing dialysis had an annual rate of staph infections that was 100 times higher than adults who are not on dialysis.

While the study found that staph infections dropped 40 percent between 2014 and 2019, it still shows that there’s a lot of work left to make dialysis treatments safe for all patients in the United States.

Hispanic, Latino, non-Hispanic Black Americans were disproportionately affected by dialysis-linked bloodstream infections, since there are race, ethnicity, and social determinants of health affect the development of end stage kidney disease. These populations are at a higher risk for kidney disease partially due to higher rates of diabetes and hypertension.

“Overall for Hispanic patients after adjusting for other factors, we found a 40 percent higher risk of bloodstream infection for that group,” said study author Shannon Novosad, dialysis safety team lead in the CDC’s Division of Healthcare Quality and Promotion, during the briefing.

[Related: The US’s healthcare system discourages people from getting care, new study says.]

The type of access used in dialysis treatment was also important, as patients who were connected to a machine with a central venous catheter had a higher risk of infection. Using this method, a thin tube is directly inserted into a vein, typically in the neck or chest. The other end of the tube is outside of the body, where it can be exposed to germs.

“Our data confirm this use of a central venous catheter as a vascular access type has six times higher risk for staph bloodstream infections, compared with the lower risk, lowest risk fistula access,” said Novosad.

Using grafts (small, plastic tubes that are connected to an artery and a vein) and fistulas (which join an artery and a vein directly) were deemed to be safer methods by the report.

“Removing barriers to lower risk vascular access types for dialysis treatment is a critical step for preventing infection,” said Novosad. “It is vital to coordinate efforts among patients nephrologists, vascular access, surgeons, radiologists, nurses, nurse practitioners and social workers to reduce the use of central venous catheters for dialysis treatment. It’s also critical to educate patients on potential treatment options and vascular access types before they develop end-stage kidney disease.”