Hurricane Lane fell apart in spectacular fashion as it meandered south of the Hawaiian Islands on Friday. The storm rapidly weakened in the face of wind shear to become a disorganized tropical storm mainly producing heavy rain.

But while the storm isn’t nearly the wind threat it was just a couple of days ago, as we’ve found out too many times in recent years, it doesn’t take a strong storm to leave behind major flooding. Flooding will remain a serious concern through the weekend. The National Weather Service issued flash flood warnings across most of Maui and Big Island on Friday.

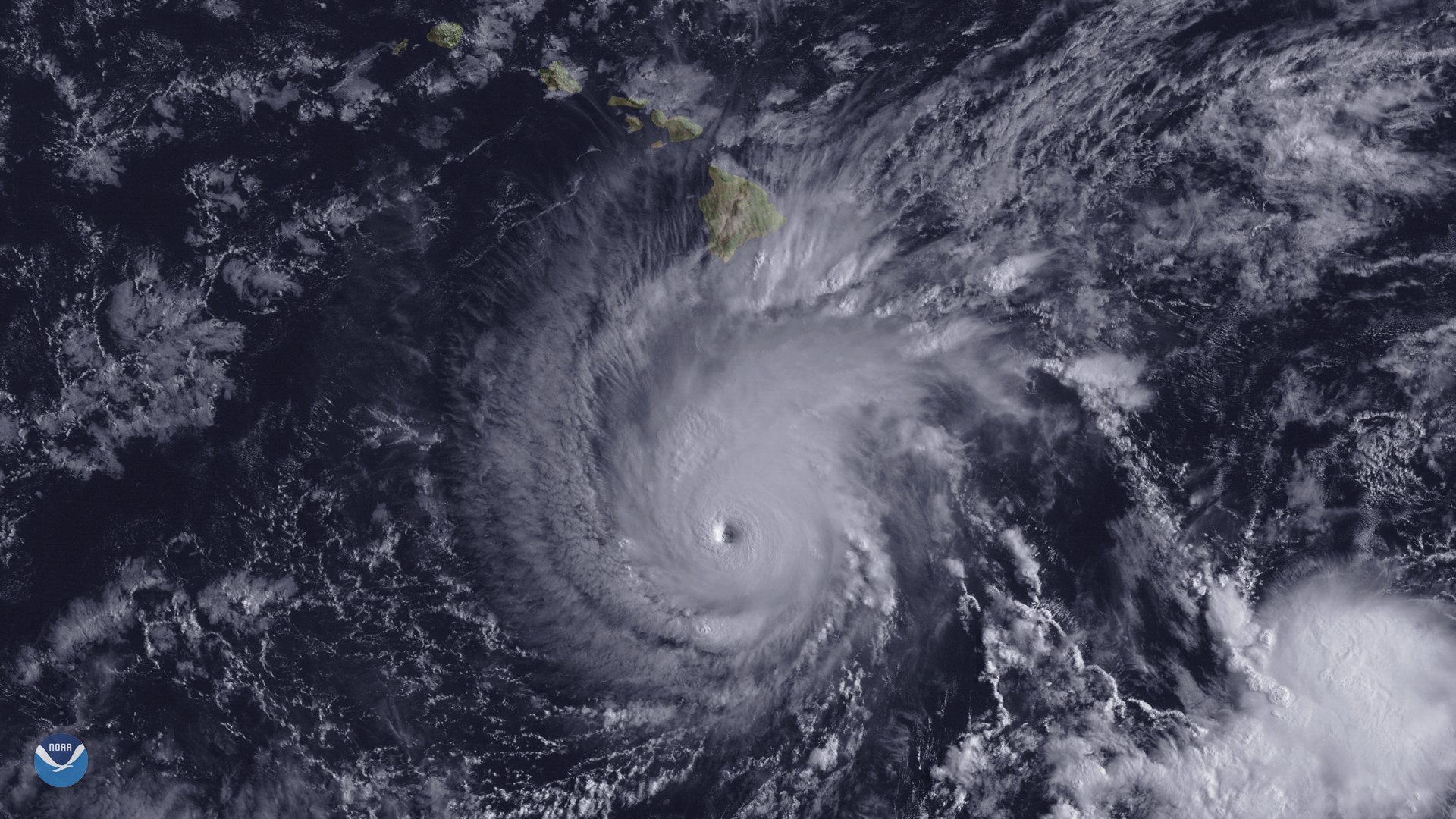

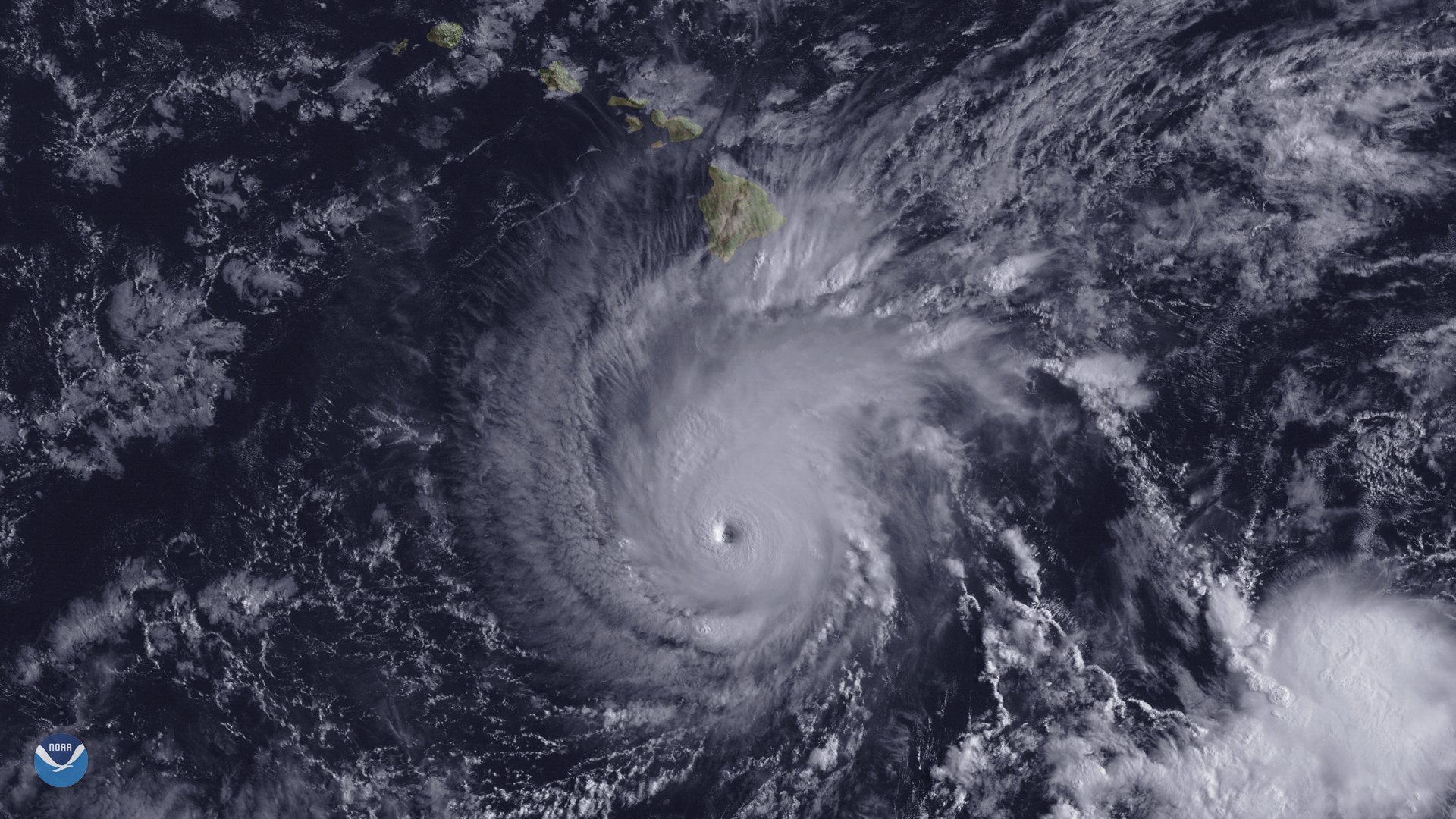

Lane is quickly weakening as it encounters less-favorable environmental conditions just south of Hawaii. Wind shear ate away at the storm on Friday, decoupling its thunderstorms from the center of circulation. This caused the storm to rapidly collapse in just a couple of hours, leaving it ragged and disorganized—a far cry from the monstrous category five hurricane it was just a couple of days ago (for a reminder on how storm categories work and why we use them, click here). Thankfully, the threat from the storm’s winds will diminish as the storm loses organization. However, even modest gusty winds can easily topple trees and power lines when the ground is soft and wet.

Although Lane’s winds are less of a concern, appearance isn’t everything when it comes to tropical cyclones, a lesson we learned from storms like Hurricane Harvey in 2017 and Tropical Storm Allison in 2001. Even a disheveled tropical cyclone can still produce torrential rainfall. Lane’s precipitation is displaced to the right of the center of circulation, exposing the islands to heavy rain even as the storm weakens.

Hurricane Lane’s lasting legacy will be the historic flooding it’s unleashed on the 50th state. The mountainous terrain of the Hawaiian Islands can make intense heavy rainfall events a dire situation. Flash flooding is a significant hazard near waterways and valleys and mudslides are likely in mountainous areas. The combined power of floods and mudslides will likely damage buildings, wash out roadways, and damage power and water infrastructure on the islands.

The heaviest rain has fallen on the Big Island, where the rain rate is exacerbated by the enhanced lift of winds flowing over the island’s tall volcanoes. An observing station in Hilo reported 16.99 inches of rain on August 23 alone. Many locations on the Big Island will wind up with more than 30 inches of rain by the end of the storm, especially on the windward sides of the island. Because the storm is moving so slowly, it’s hard to know how long it will hover close enough to the archipelago to continue dumping precipitation.

Rainfall totals in the double-digits are also possible on the most populated island of Oahu by the end of the storm. A small storm surge is also possible near Honolulu, which, combined with high surf, could lead to coastal flooding and beach erosion.

The rain on Maui will be a double-edged sword. A wildfire that broke out on the island on Thursday rapidly spread through the day on Friday as a result of the storm’s gusts. Heavy rain should help firefighters contain and extinguish the flames this weekend.

“We were expecting flooding, high winds, big surf—we weren’t expecting very little rain, heavy winds and a big fire,” the mayor of Maui, Alan Arakawa, told the New York Times. “We’re hoping for just enough rain to put out the fires, not enough rain to have mudslides after that.”

Hurricane Lane is a rare event in Hawaii. The state experiences fewer hurricanes than you’d think for its location in the tropical Pacific Ocean. The most common tropical threat Hawaii faces is storms passing the island chain to the north and south or weak tropical waves bringing flooding rains as they pass through the region. No hurricanes on record since 1950 have approached all seven populated islands along Lane’s path—previous storms only struck one or two islands, like Hurricane Iniki in 1992, which devastated Kauai while leaving the other islands relatively untouched.