Though they may come as a surprise, heart attacks don’t just happen at random—chances are, years of poor diet and not enough exercise set the stage for a heart attack to occur. Over the past few years, researchers have learned that genetics also play a role, discovering variations that increase a person’s chances of having a heart attack. Now scientists have discovered another mutation that does the opposite: people who have it run a 50 percent lower risk of having a heart attack. They also had lower levels of triglycerides in the blood, both of which might provide a new target for medications intended to prevent heart attacks. The research was published last week in the New England Journal of Medicine.

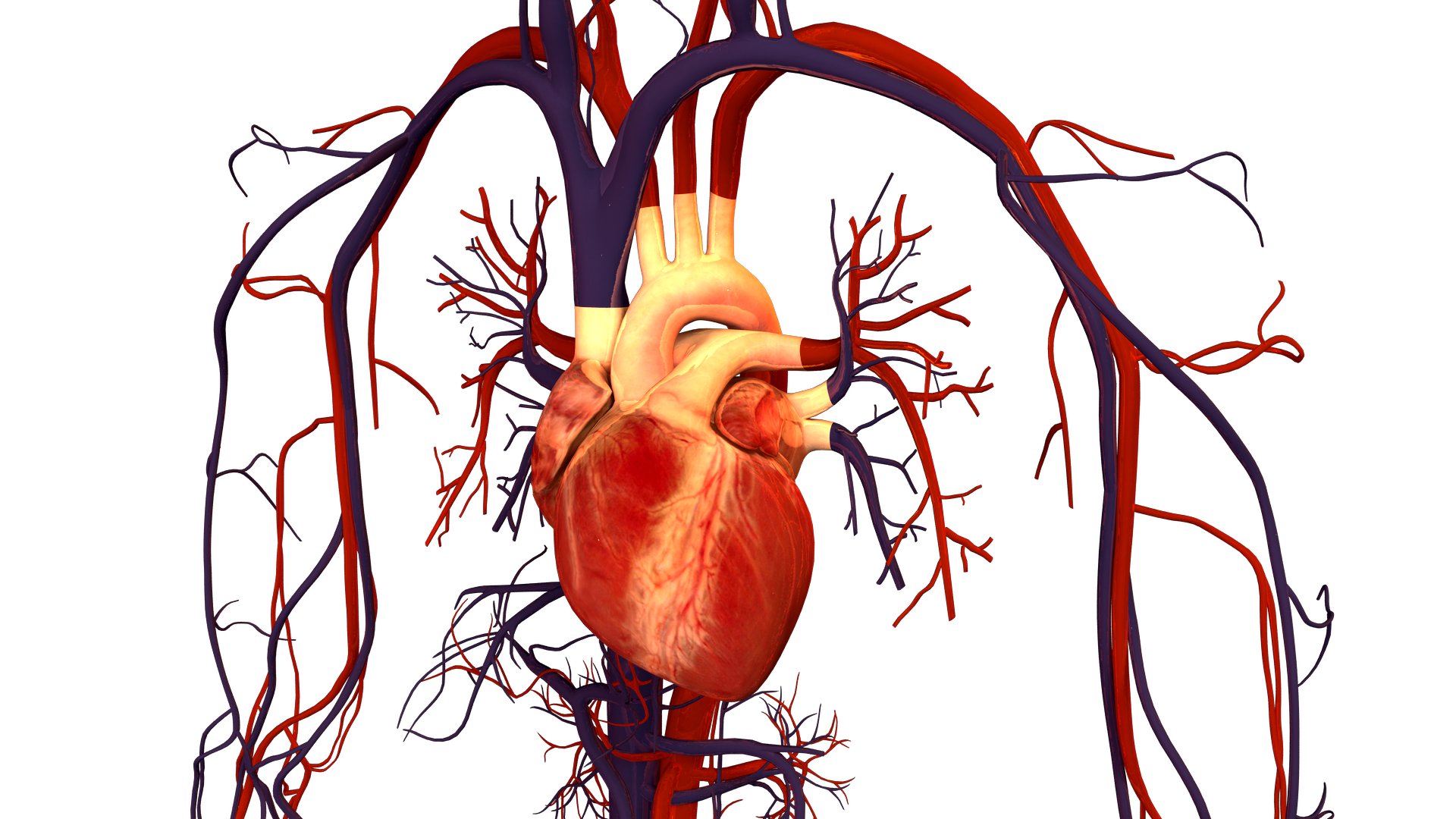

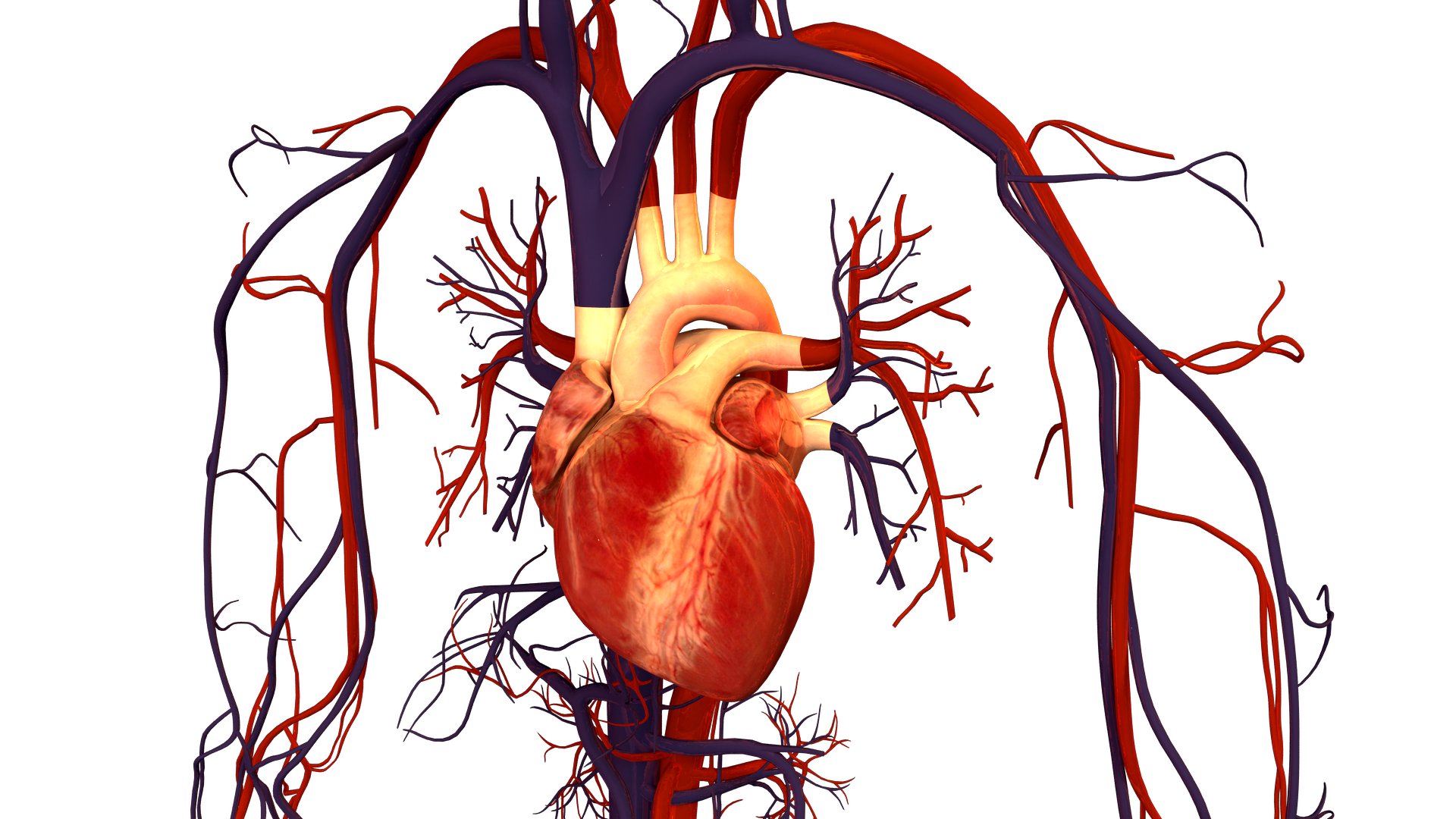

Over the course of four years, the researchers analyzed 13,000 genes from 200,000 patients, looking for correlations between mutations and coronary artery disease, a condition in which the main blood vessels leading to the heart become clogged and could lead to a heart attack. They found that patients who had a mutation on a gene called ANGPTL4 had a much lower incidence of heart attacks. They also had much lower levels of triglycerides, a type of fat found in the blood; high levels of triglycerides have been linked to heart disease.

Here’s what the researchers think is going on. If ANGPTL4 is functioning properly, it inhibits the lipoprotein lipase (LPL) enzyme, which is found in the blood and used to break down triglycerides. If ANGPTL4 doesn’t work, the LPL enzyme keeps working, lowering the triglycerides found in the blood. Over time, that could limit the amount of fat deposited in the arteries, reducing a patient’s risk of heart attack.

To the researchers, this work yields two conclusions that are important to clinical practice. First, doctors have been underestimating the importance of triglycerides as an indicator for heart attack risk—they’ve been focusing on cholesterol instead, which has been fraught in recent years as patients try to distinguish between what’s “good” and “bad” for them. These findings suggest that encouraging patients to lower their triglyceride levels might help doctors lower the risk of heart attack.

Second, ANGPTL4 could be a new target for medication. The body doesn’t need the gene at all, the researchers say, so new medications could shut it down completely to help at-risk patients stave off heart attacks. Further studies would need to prove that ANGPTL4 really isn’t necessary—it’s already been done in animals the researchers say, though in general genes can turn each other on and off and interact in surprising ways. If the researchers are correct, new medications could help people keep more LPL enzyme in their blood, lowering their triglyceride levels and reducing their risk for heart attack.