Millions of people are expected to turn their heads skyward to watch the Great American Eclipse on August 21. You might be one of them. But did you know that you can enjoy this natural wonder while also helping scientists out? Here are four ways that you too can be an eclipse scientist—at least for a day.

1. Watch the thermometer drop for NASA

If you’ve ever wanted to join NASA, well, this won’t quite get you there—but you’ll still be working hand in hand with the organization that sends astronauts into space. The Global Learning and Observations to Benefit the Environment (GLOBE) Program is trying to gather an army of eclipse-watchers across the country to collect data on changes to temperature and cloud cover when the moon momentarily obscures the sun. To get a sense of what your measurements could become, check out the data that GLOBE has already collected with the help of citizen scientists.

What you’ll need: a smartphone, the GLOBE Observer app, and a thermometer

Do I need to be in the direct path of the eclipse?: No! You can submit data from anywhere in North America, even if you only see a partial eclipse

How to participate:

- Download the free app (Android or iOS) and make an account.

- On August 21, head outside and make observations of the cloud cover every 15-30 minutes for two hours before and after the peak of the eclipse.

- If you also want to collect temperature data, place your thermometer in the shade and take measurements every 10 minutes for two hours before and after the peak of the eclipse, and every five minutes for half an hour before and after the peak of the eclipse.

- As a bonus, record the temperature 24 hours before the eclipse.

Extra-credit: Get trained in the surface temperature protocol so that you can use an infrared thermometer. And if you have a wind speed gauge, you can even measure changes in wind speed or direction.

2. Lights out, cameras rolling for the Eclipse Megamovie

It’ll only take the moon a couple of minutes to pass across the sun. But that’s just from one point. The eclipse will actually take 90 minutes to complete its cross-country road trip from Lincoln Beach, Oregon, to Charleston, South Carolina. What if we could film this entire journey?

That’s just what Hugh Hudson, a research fellow at the University of Glasgow, and Scott McIntosh, director of the High Altitude Observatory at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, dreamt up at a conference in 2011. “We looked at each other and said, ‘Let’s make a movie,'” Hudson says.

The Eclipse Megamovie project is enlisting citizen scientists to take photos from various points across the country, which will then be stitched into one movie detailing the extent of the eclipse. The data will be more extensive than any previous time-lapses of solar eclipses, Hudson says.

“The timing of the shadow across this huge path gives you a lot of new information,” Hudson says. “Normally when an eclipse happens, it’s a one-off snapshot. Now we’re seeing a three-dimensional thing.”

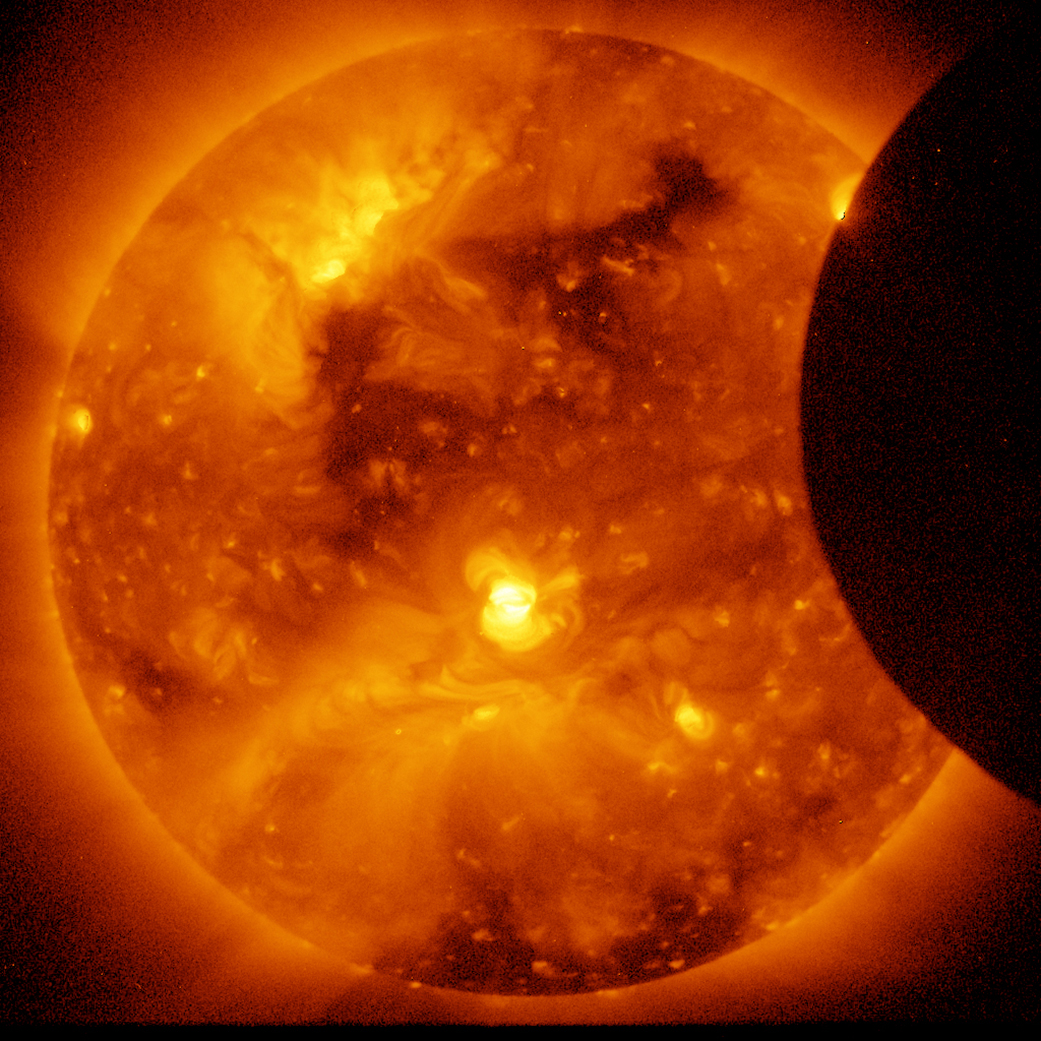

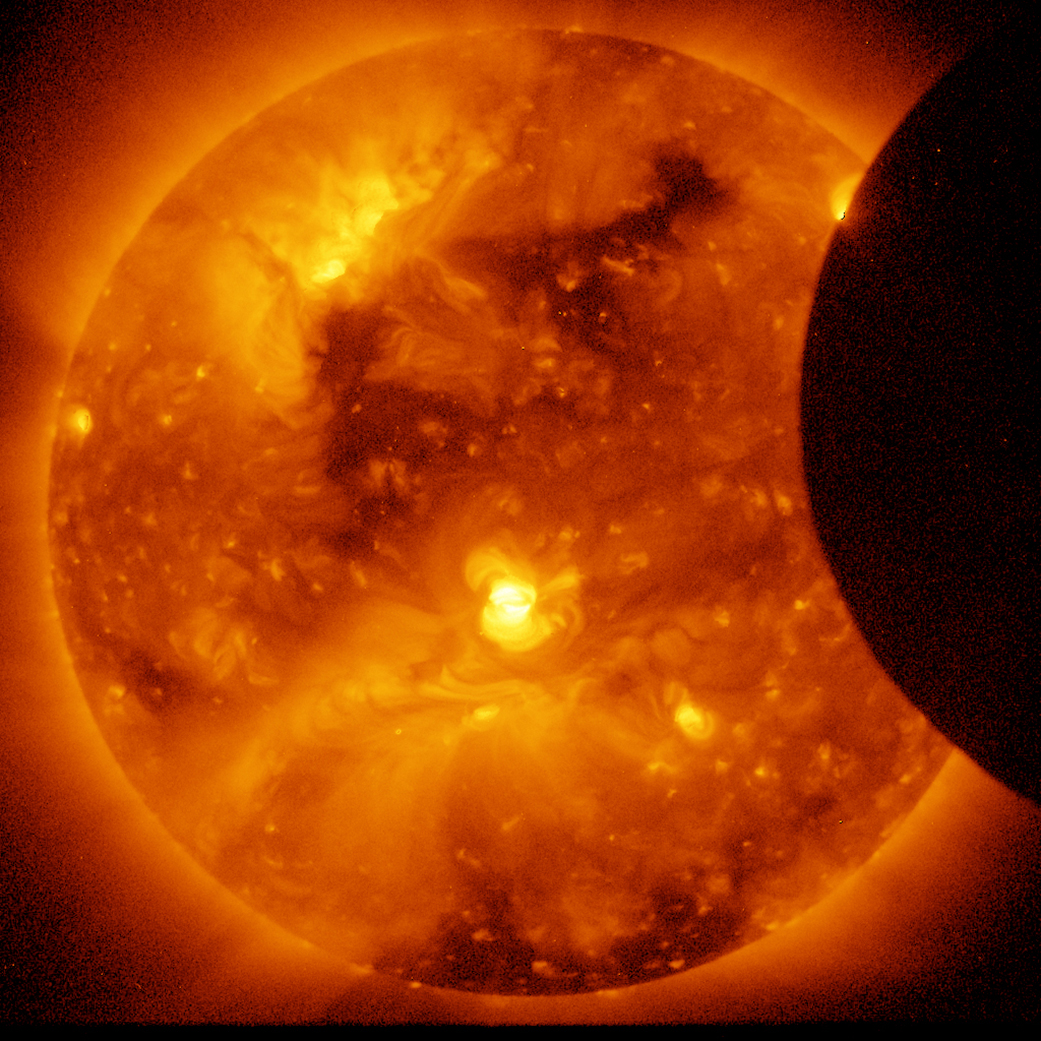

The data will help scientists understand the corona (the glowing gases that surround the sun) and special eclipse features like the diamond ring, as well as helping them measurements (like the radius of the sun). A week ago, they hit their goal of 1,000 volunteers for their official project, where trained observers will take photos with a DSLR camera.

“Any DSLR with a good lens is better than any telescope put in space,” Hudson says.

But they’re not done yet: sign-ups are continuing, and they hope to get one or two thousand more volunteers. Even without a fancy camera, observers can still take great eclipse photos—the Eclipse Megamovie app will do the heavy lifting to ensure that even phone shots are high quality and tagged with the location and time. There may even be opportunities after the eclipse to help sift through all the photos to find the ones that capture important features.

What you’ll need: Either a DSLR camera or a phone with a camera (external lens is optional, but a fun addition) and the Eclipse Megamovie Mobile app.

Do I need to be in the direct path of the eclipse?: Yes, the total eclipse is the star of this show.

How to participate:

- Download the Eclipse Megamovie Mobile app (Android or iOS)

- No matter what camera you’ll be using, whether a DSLR or a smartphone, the app will guide you through how to take the best photos of the eclipse.

- Practice makes perfect—use Practice Mode on the app to refine your technique.

- On the night of the eclipse, just point your smartphone’s camera at the sky and let the app do the work, or use your own camera. Share your photos with scientists (and get some high-quality photos for yourself to mark this once-[or twice- or thrice-]in-a-lifetime event).

Extra-credit: If you have a DSLR camera and tripod, you may be able to participate in the official Megamovie. Details are on the website.

3. Feeling crafty? Join the EclipseMob

Up in the sky, over 600 miles above the ground, is the land of radio waves. It’s called the ionosphere, and eclipsemob/”>EclipseMob wants your help to study it.

When the sun’s rays pass through the ionosphere, the radiation giving the atoms a slight electromagnetic charge. This can interfere with radio waves, but the eclipse provides the perfect opportunity to see what happens in the sun’s absence.

It’s not the first time that the eclipse has been used as a real-world laboratory. During the total solar eclipse on April 17, 1912, British physicist William Eccles listened for clicks and other abnormal noises on a radio station. But this time, citizen scientists from around the United States will use homemade radio antennae and receivers to measure one radio wave in particular, broadcast from a government station in Fort Collins, Colorado. By comparing the wave’s signal in Washington to its signal in Florida, for example, you can figure out how the radio wave changes when it has to pass through the path of the eclipse—and it will all be geotagged and timestamped by the EclipseMob app, designed to help people collect the data.

“With citizen science, we’ll have data from lots of different locations in the United States,” says Jill Nelson, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at George Mason University.

Unlike Eccles’ experiment, which only used one receiver, this study will have over 150: That’s how many people from eclipsemob/images/EclipseMob-Map-0707.png/”>across the country have signed up and received kits containing all the materials they’ll need to build their very own antenna and receiver.

“One of the unique things about this project is the design,” says Laura Lukes, program manager and affiliate assistant professor of atmospheric, oceanic, and earth sciences at George Mason University. “[The receiver] doesn’t require special materials or soldering, which increases the accessibility. Engaging the nationwide community and the average citizen, that’s the only way we can get a large enough dataset.”

What you’ll need: The parts to construct an antenna and a receiver, a smartphone with a headphone jack, and the mobile app.

Do I need to be in the direct path of the eclipse?: No! EclipseMob wants to figure out how radio waves change depending on how far they are from the eclipse or how they’re oriented. They’re especially eager for more volunteers in the eclipsemob/images/EclipseMob-Map-0707.png/”>midwest.

How to participate:

- Follow the instructions to construct your antenna and receiver.

- Connect it to your phone via the headphone jack.

- Starting before the eclipse (the amount of the time will depend on your location), set up your antenna system and connect it to your phone via the headphone jack.

- Use the app on your phone to fine tune your antenna system: The app will tell you when you’ve picked up the right signal and it’ll help you visualize what the graph of the signal should look like.

Extra-credit: There’s been more demand than available kits, but if you didn’t sign up in time to get a kit, don’t worry—Lukes and Nelson have put together a list of parts that you can use to build your own antenna and receiver.

4. Calling all bird-watchers and chicken-owners: Watch how “Life Responds.”

This isn’t Elise Ricard’s first rodeo. Ricard, the public programs presenter supervisor at the California Academy of Sciences, was actually in Australia in 2012 for their total solar eclipse. “I remember birds going quiet,” Ricard says. “It was a distinct, vivid experience.” Scientists have studied plants’ and animals’ responses to the sudden absence of the Sun during solar eclipses, and this year, Ricard hopes citizen scientists can help these efforts through the “Life Responds” project.

After all, when the sun’s light gets snuffed out, both plants and animals might think that nighttime has come (early): Birds’ flight patterns could change, some plants will close up, farm animals might even return to their sleeping areas. (That’s right, if you have chickens, keep an eye on them!) And since the eclipse will be passing over relatively rural parts of the country, eclipse watchers will likely be surrounded by nature—all they need to do is snap a few photos or jot down some notes.

The California Academy of Sciences has been partnering with other citizen scientist initiatives and state parks to get the word out. Although they don’t know how many people will submit photos, they’re hopeful that the data will be useful for scientists. They’ll be publishing a summary and all the raw data will be available online.

“Citizen science is a truly beautiful thing,” Ricard says. “It gives people a direct connection to research being done and it allows people to participate on a scale that is unprecedented.”

What you’ll need: A smartphone and the iNaturalist app

Do I need to be in the direct path of the eclipse?: No! In fact, Ricard says data from all over the continental United States will be particularly helpful because it will help them figure out what percent of darkness or what degree of temperature change is required for plants and animals to react.

How to participate:

- Download the iNaturalist app (Android and iOS) and make an account.

- Join the “Life Responds” project.

- Play around with the app and get familiar with it.

- On the big day, pick the plants and/or animals you’ll be observing.

- Take photos of your chosen organisms 30 minutes before, during and 30 minutes after the total eclipse. When they say “during,” they mean at least within five minutes of the eclipse—they know you might be too awestruck to take photos, and besides, it’s more important that you experience the moment.

- You can also take notes describing what you see and hear. Your observations will be geotagged automatically.

Extra-credit: It’s important to make multiple observations (at the very least, before and after, or during and after) so that you can see the change. But the more data, the better! And the California Academy of Sciences keeps the iNaturalist app going all the time, not just during the eclipse, so continue keeping an eye out for natural phenomena that might make a good addition to its growing collection.

And if this isn’t enough science for you, check out NASA’s list of citizen science initiatives during (and beyond) the total solar eclipse.