We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

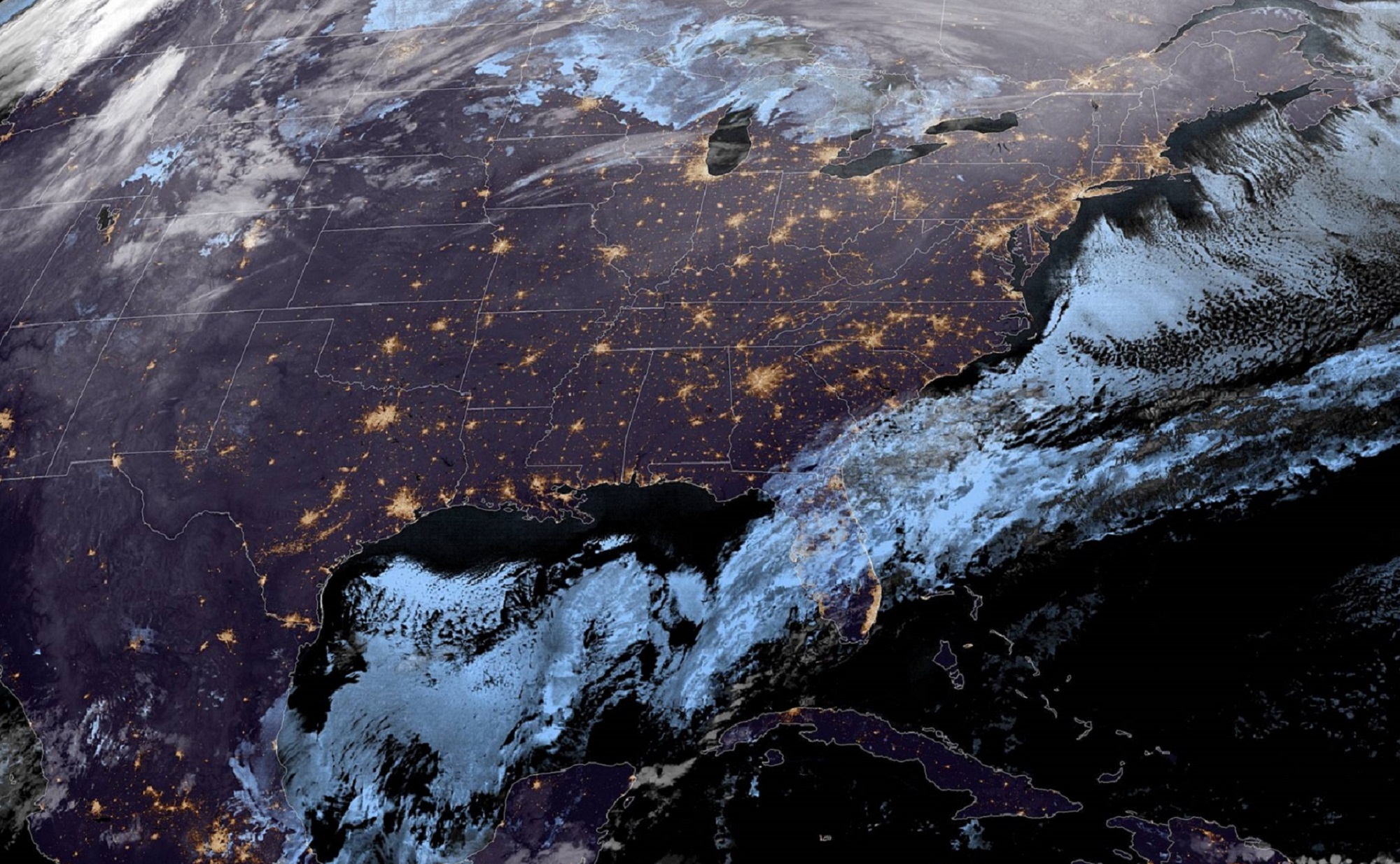

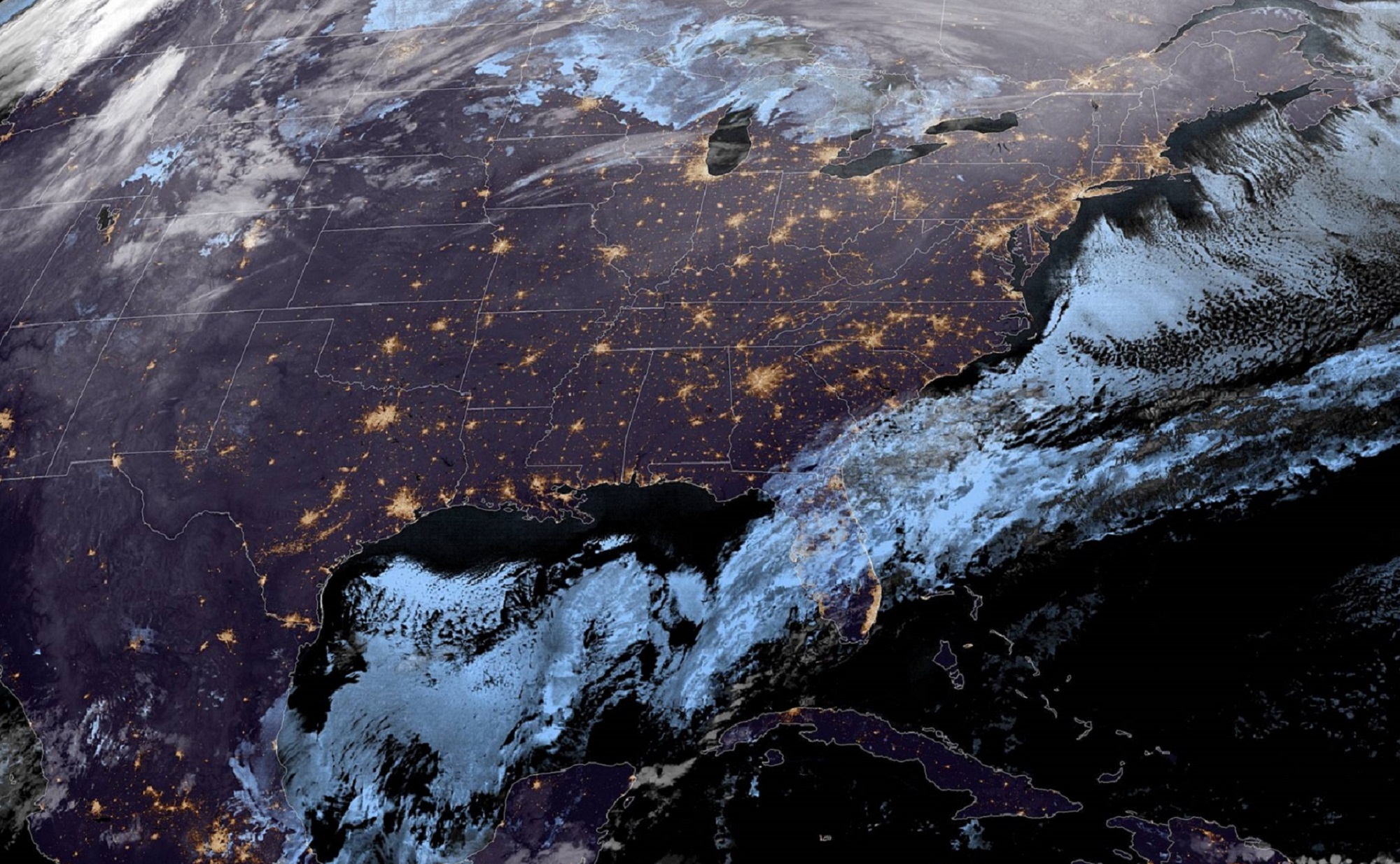

A winter storm—just shy of a year after the storm that toppled Texas’ power grid last year, killing hundreds—has swept across the central United States and is making its way up the East Coast. Although most of the snowfall has passed, “bitterly cold temperatures will span an area from the Southern Plains to the Ohio Valley and Northeast,” the National Weather Service predicts.

On the storm’s southeastern edge, tornadoes in Alabama killed one person and critically injured eight others. There were also three deaths in Texas due to accidents from icy road conditions.

The storm is being referred to as Winter Storm Landon, although that’s not an official name given by the National Weather Service—it comes from the Weather Channel, which began naming winter storms 10 years ago. But it follows a trend toward naming more extreme weather events, like heat waves, in an effort to communicate their risks to the public.

On Thursday, more than 70,000 Texans lost electricity, despite promises by the state governor last year that “the lights will stay on” over the winter. By Saturday, about 2,000 homes are out of power, concentrated in Hunt County, just northeast of Dallas, where temperatures dropped into the teens the previous night. Still, the Texas power generation system doesn’t appear to have reached the brink of complete collapse, and the Texas Tribune reports that the peak load on the grid has passed.

[Related: The jet stream is moving north. Here’s what that means for you.]

The storm started when a loop of the jet stream, which carries high-altitude weather from west to east, bulged down over the Texas panhandle, carrying in ultra-cold, low-pressure air from the northern Great Plains. That’s how last year’s big freeze began as well. But unlike that storm, which stalled over Texas after a blockage in the jet stream, this one is fast-moving, driven by temperature contrasts between the Southeast and Midwest.

That sets it apart from a number of recent disasters, like the floods in Germany and the heat domes in the Pacific Northwest last summer, that have been the result of buildups in the jet stream. Such changes in the jet stream and other extreme weather have been linked to climate change by some scientists, although the connection is still an open question.

With Winter Storm Landon, the cold, dry air moving south sucked warm, wet air from the Gulf of Mexico inland. Where the two air masses met, in a band stretching from Dallas to Maine, much of that moisture fell as snow, sleet, or rain. The Washington Post reported that in parts of western Kentucky, three-quarters of an inch of ice had built up on tree branches.

Many of the 300,000-plus power outages in Tennessee, Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and New York appear to be caused by the ice itself, rather than grid failures. The glaze can add thousands of pounds to trees. If they topple or shed limbs, they can take out power lines, leading to the same kind of widespread outages that follow a major windstorm. A Texas NBC station even reported that some trees made explosion-like sounds as water froze and expanded in the wood.

[Related: Texas’s grid may still be unprepared for the next big winter storm]

The heat on the eastern side of this storm—Alabama was nearly 70 degrees on Thursday—was responsible for the outbreak of tornadoes, which spawn underneath particularly turbulent thunderstorms. Like hurricanes, they’re normally a product of summer heat; in this case, however, the huge temperature and pressure difference between the Gulf air and the freezing air could have driven the storm’s intensity.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Gulf was nearly 2 degrees Fahrenheit warmer this past fall than expected, and waters off the Louisiana and Alabama coasts were 8 to 10 degrees hotter than normal. Over the past several years, hot water has been a key ingredient in powerful storms—particularly the rapidly intensifying hurricanes that have battered Texas, Florida, and Louisiana.

Update (February 7, 2022): The article has been updated to include new deaths in Texas. A mention of Austin’s boil-water order was also removed because the service disruption wasn’t storm-related.