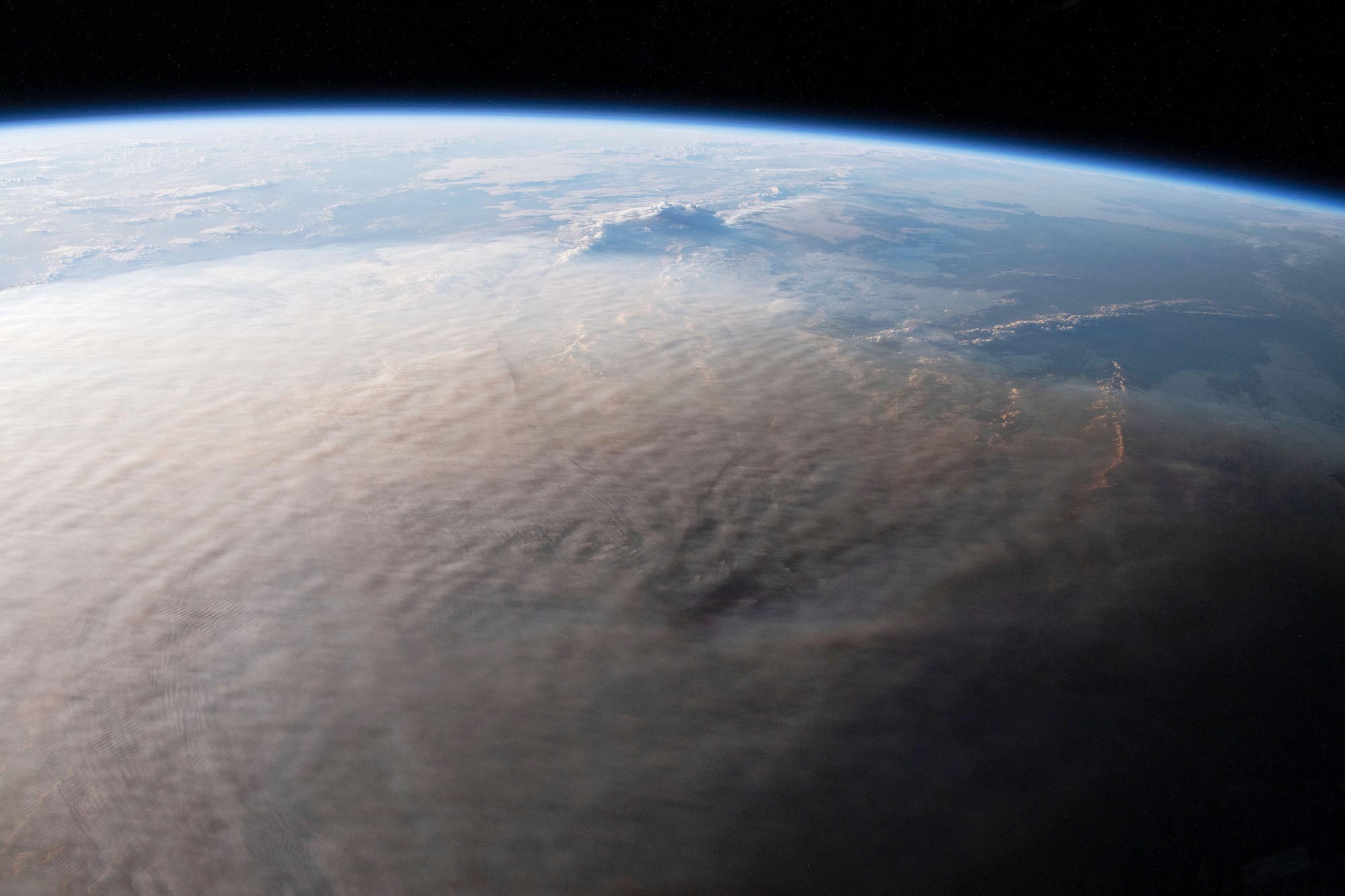

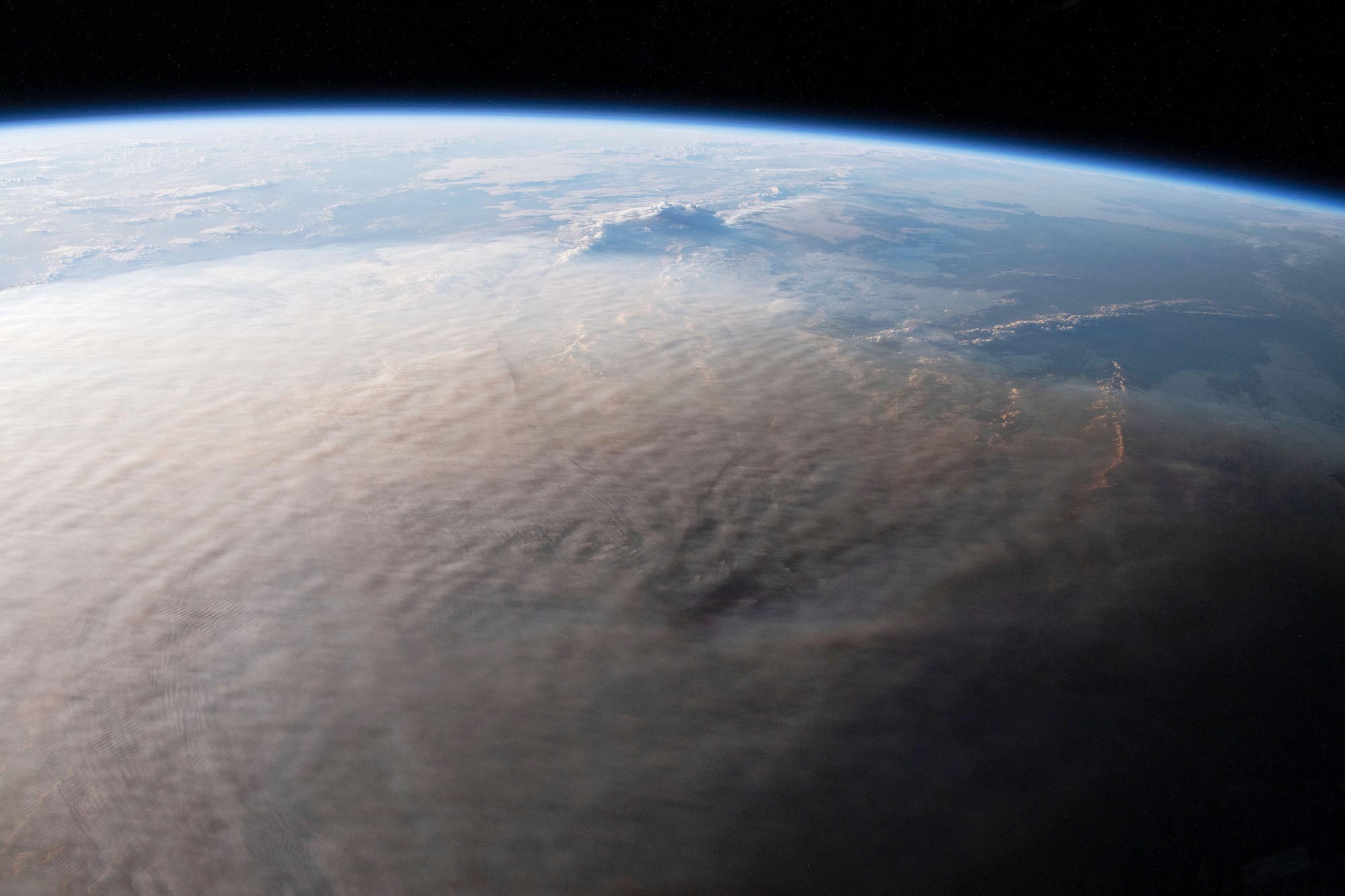

Over the past week, ships from Australia and New Zealand have delivered hundreds of thousands of gallons of water to the Pacific archipelago of Tonga, which quickly ran out of drinking water in the aftermath of a volcanic eruption on January 15. According to Tonga’s speaker of the house Fatafehi Fakafānua, many of the country’s 100,000-plus residents still have no access to water after ash contaminated its drinking supplies.

According to a report from the United Nations, relief organizations have set up 16 water stations around the island to meet that need. But the process of digging out wells and rooftop tanks has been slow-going, in part because to avoid introducing COVID to the largely disease-free islands, relief teams have remained in quarantine.

An underwater volcanic eruption is, clearly, different from climate-related storms, fires, and floods. But it highlights the vulnerability of global water systems to withstand such events, creating humanitarian disasters that linger for months. “This is really just a classic textbook case of what happens when you have one disaster on top of another,” says Craig Colten, a senior adviser at the Water Institute, a Louisiana-based water policy organization, and an expert on coastal disasters.

Tonga gets its water from two sources. Rural areas generally rely on rainwater gathered from rooftops, while urban areas tap a shallow freshwater aquifer that sits in the porous limestone that makes up the islands. This aquifer, which also forms from pooled rainfall, sits on top of saltwater, like a drop of oil on a bowl of water.

Experts studying the conditions in Tonga think it should be okay for people to drink from water tanks, as long as they wait for the ash to settle. But it’s harder to predict how the particles will affect the aquifer. When seawater boils from volcanic activity, all kinds of new chemicals can form, says Esteban Gazel, a volcanologist at Cornell University. Some of them can be acidic.

An analysis of the ash blanketing Tonga shows that is has a similar pH to drinking water, Carol Stewart, co-director of the International Volcanic Health Hazard Network, told PopSci on February 4. The islands’ limestone base is also alkaline, which means it could neutralize any acidic compounds that make their way into the groundwater. But the reserves are also close to the surface, which is why Gazel says it’s impossible to know the end result without more careful analysis of the aquifer. “I would advise the authorities in Tonga just to monitor the groundwater composition,” he adds.

[Related: The volcanic eruption severed Tonga’s internet connection, and repairs won’t be easy]

These infrastructure issues aren’t limited to Tonga. Even in the US, emergency response teams aren’t equipped to investigate all the water-quality issues that emerge after environmental crises, says Andew Whelton, a civil and environmental engineer at Purdue University who studies post-disaster water quality.

He spoke to Popular Science from Louisville, Colorado, which was razed by wildfires this past December. “For wildfires, you generally have forests full of organic materials combusting, which can transform into toxic carcinogens at levels that can cause acute harm immediately.” Those compounds start in the air, but some of them end up settling in the water, where they linger. When a fire rips through an urban or suburban area, burning plastic from home water lines can contaminate entire water systems.

Electricity is another vulnerability. When power goes out, from a freeze, fire, or hurricane, underground pipes can lose pressure and untreated groundwater can slip in. Colten says it took four months for New Orleans’ drinking water to be safe after Hurricane Katrina. “There was so much wind damage that a lot of big trees fell over and ruptured the lines. Then you had saltwater pouring into the city, getting into those fractured water lines. That put a lot of undrinkable stuff in the systems.”

Take Hurricane Maria, for instance. After the storm hit Puerto Rico, it took nine months for clean water to be restored because of the US territory’s limited resources. In the meantime, the Environmental Protection Agency found that many of the waterways that residents turned to were contaminated by sewage.

Then there are floods, which can submerge water treatment facilities, carrying in sewage and industrial chemicals that clog up filtration systems.

[Related: The US is losing some of its biggest freshwater reserves]

The short-term American response to disasters looks a lot like what’s playing out in Tonga. The Federal Emergency Management Agency sets up drinking water outside the impacted area, and trucks in bottles and tankers. But getting access to that relief can be another story. In the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey in Houston and Hurricane Ida in Louisiana, massive lines formed for bottled water.

But the damage from a disaster can play out for much longer. “As an industry, we train engineers how to design water treatment facilities, and what chemicals the EPA routinely tests for,” says Whelton. “We do not train people for a wildfire where people are complaining about paint-thinner odor, and you have to figure out what that is.”

Whelton gives the example of the 2018 Camp Fire, the deadliest fire in California’s history. Afterwards, a state lab reported benzene contamination in a water system. “I asked them to send me the laboratory data,” Whelton says. “That showed that the water sample was lit up like a Christmas tree with a bunch of other chemicals there. It wasn’t because California wasn’t trying to do the right thing—it’s that they didn’t have people who knew how to handle situations where you don’t know what chemicals are in the water.”

Identifying the specific substance is important because it determines how long the water supply will be contaminated. If there’s bacteria, the water can simply be boiled; but some chemicals might require that all of it be flushed. Others might soak into plastic plumbing and leach out over time, requiring the replacement of the whole system.

These issues compound with climate change, across the US and beyond it. As Tonga digs out of the volcanic ash, its water table is being pushed higher by sea level rise, which also leaves it more vulnerable to major hurricanes. The UN projects that in the next 50 years, there’s a 2 in 3 chance that more than 20,000 Tongans will be displaced by a hurricane. Each disaster can leave a system more vulnerable to the next blow.

Correction (February 3, 2022): This story has been updated with new information from the International Volcanic Health Hazard Network on the pH levels of the ash and safety of the drinking water in Tonga. The section describing the dangers of acidic compounds in drinking water have been updated. The information wasn’t specific to the volcanic eruption in Tonga, and reporting did not properly contextualize that information.