Summer in the southwest US is already proving to be a scorcher. Since June 9, Las Vegas, Nevada has been caught in a heat dome, a kind of atmospheric pressure cooker that superheats air near the ground. Record-breaking heat hit the area, with temperatures consistently soaring to triple digits. On June 10, 2022, the city reached a record daily high of 109 degrees Fahrenheit—so hot that the heat was picked up by sensors in space.

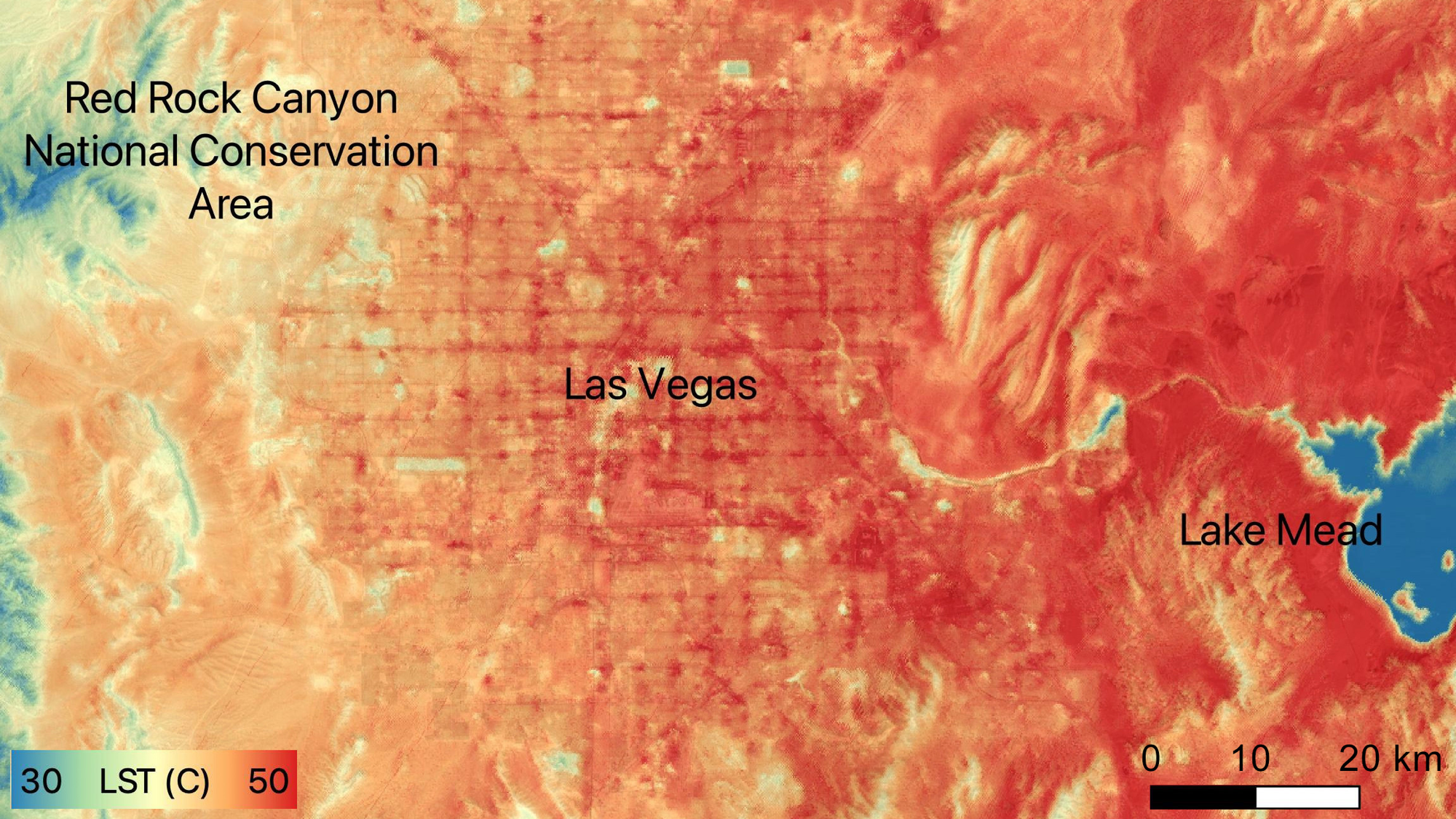

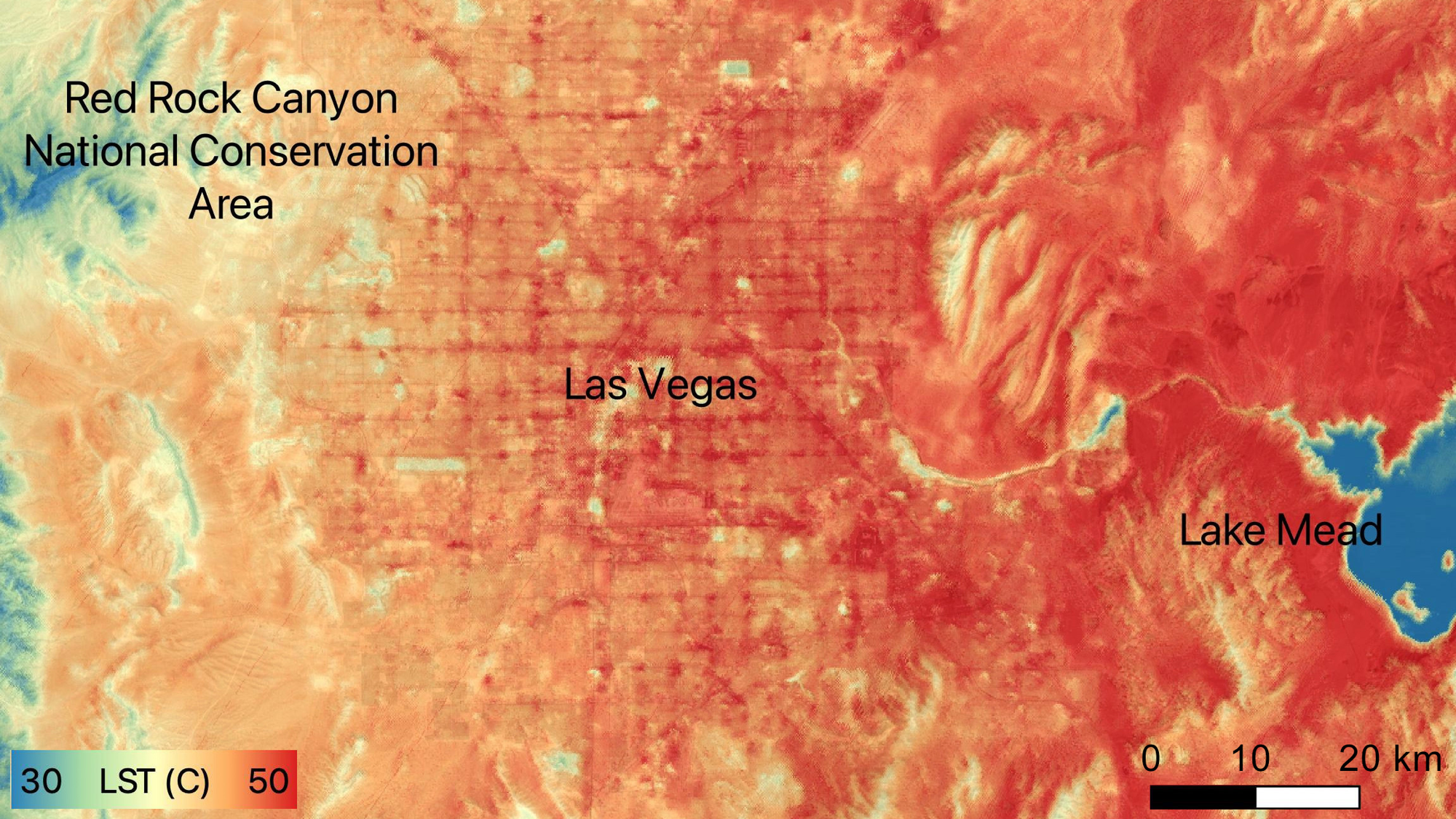

NASA’s Ecosystem Spaceborne Thermal Radiometer Experiment on Space Station, or Ecostress, generated a map of land surface temperatures of Las Vegas and the surrounding community. Recorded at 5:23 pm when heat peaked, the map reveals it radiating out from the city center from red to yellow.

[Related: A ‘heat dome’ is searing the US with record-breaking temperatures.]

The map is a stark illustration of the “urban heat island” effect, which magnifies the dangers of extreme heat in cities. Human activity, vehicles, buildings and streets all soak up more heat (and take longer to cool off) than places that are less developed and have more vegetation.

“Even in a place like Las Vegas, which is in the desert, and there’s low tree canopy cover in the first place, you can see that places where there are less trees are hotter,” says Chris David, vice president of data and mapping at American Forests, which did a survey of tree canopy and vulnerability to heat in American cities in 2021.

Explore data on tree cover, heat islands, and “tree equity” in Las Vegas in American Forests’ tool below:

The Ecostress project is set up to monitor water loss from plants in a warming climate, but it also provides a street-level view of heat waves. The instruments, aboard the International Space Station, specifically target ground temperature over air temperature because it’s typically hotter at the surface. This is reflected in the map’s darker red grid pattern—pavement temperatures even exceeding a broiling 122 degrees Fahrenheit.

“This is basically a Las Vegas street map,” says David. Asphalt absorbs up to 95 percent of solar radiation, which means that the material emits additional heat at ground level where people are walking and living, he explains. “If people are outside, it’s critical that they have some shade.”

Other regions of the US have also been bombarded by blistering heat. Excessive heat warnings and heat advisories have impacted more than 95 million people from the southwest to Florida to northern Michigan, according to the Washington Post. “We all know that when flash flooding or thunderstorms or hurricanes are coming, we better take care of ourselves,” Erick Bandala, assistant research professor of environmental science at the Desert Research Institute in Las Vegas, told the Washington Post. “But not really about extreme heat. It’s probably one of the most under-considered risks that we can be facing.”

As climate change brings more frequent and more intense heat waves, heat-related injuries and deaths are a growing concern, and especially afflict low-income and minority communities. People of color are more likely to live in hotter cities with urban heat islands (sometimes up to 20 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than communities of predominantly white high-income residents), and therefore wrestle with issues brought by heat.

“This is part of the history of redlining in the US—sticking poor people, and people of color, in those neighborhoods that are right next to the highway, that have poorer air quality, higher levels of impervious surface, higher temperatures,” says David.

Last year, a similar heat dome settled over Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia, killing hundreds as temperatures rose to nearly 110 degrees Fahrenheit. During that heat wave, deaths in Portland were concentrated in neighborhoods with lots of asphalt, and few trees. “It just proves that trees really can be life or death infrastructure,” David says.