Parrots, renowned for their impressive intelligence and charming vocal mimicry, have gained popularity as pets in recent decades. Those same traits that make the birds fascinating to observe, however, can also cause issues. A lack of socialization and proper stimulation can cause parrots to act out, or in some cases, even harm themselves. An estimated 40% of cockatoos and African Greys, two popular species of parrots, reportedly engage in potentially harmful feather destruction. Many of these stress-induced, destructive behaviors are a byproduct of parrots living in environments drastically different from their natural habitats where they fly free among fellow birds. New research suggests modern technology, specially Facebook Messenger video chats, could help these birds regain their social lives

“In the wild, they live in flocks and socialize with each other constantly,” University of Glasgow associate professor Ilyena Hirskyj-Douglas said in a statement. “As pets, they’re often kept on their own, which can cause them to develop negative behaviors like excessive pacing or feather-plucking.”

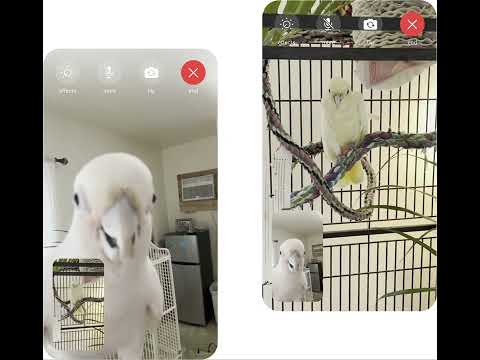

Researchers from Northeastern University, MIT, and the University of Glasgow recently set out to see how several species of parrots interacted when placed on brief video calls with one another. Over the course of three months, the researchers trained 18 parrots and their human caretakers to learn how to operate touchscreen tablets and smartphones. The birds were initially trained to associate video calls with a bell. Everytime the bell was rung during the training phase, the bird would receive a treat. Caretakers, meanwhile, were trained to end calls any time the bird showed signs of stress or discomfort. Once trained, the birds were free to ring the bell on their own accord. Doing so would result in their caretakers opening up Facebook Messenger and connecting them with fellow birds around the country involved in the study. associated video calls with a bell and fed the birds a treat every time they rang the bell. The parrots were then able to access Facebook Messenger to video call fellow birds around the country.

The results were shocking. In almost all cases, the birds’ caretakers claim the video calls improved their well-being. Some of the birds even appeared to learn new skills, like foraging or improved flight, after observing other birds doing so. Two of the birds, a cockatoo named Ellie and an African Grey named Cookie, still call each other nearly a year later.

“It really speaks to how cognitively complex these birds are and how much ability they have to express themselves,” Ilyena Hirskyj-Douglas said in a statement. “It was really beautiful, those two birds, for me.”

Bird video-calls resulted in long-lasting friendships

The research into the birds was split up into two phases. For the first 10 weeks, caregivers were instructed on how to introduce and train the birds to interact with the touchscreen devices. Though previous research has explored using touchscreen with cats, dogs, bears, and rodents, parrots are particularly well suited to using the devices thanks to their combination of high cognitive ability, impressive vision, and flexible tongues. Once trained on the devices, all of the birds involved took part in a “meet and greet” where they were briefly placed in video calls with each bird at least twice. The birds were trained using treats to ring a bell to signal their interest in hopping on a call.

Stage two of the research removed the treats to see if the birds would still have any interest in requesting a video call without a food reward. Every one of the birds continued to ring the bell, with some doing so many times. Once rung, researchers presented the birds with a tablet home screen featuring photographs of different birds in the study. The parrot would then use its tongue to click on the companion it wished to interact with. Once presented with a bird on the other side of the call, the parrots would hop towards the screen, let out loud squawks, and bob their heads. Researchers believe the vocalizations in particular may mirror the type of calls and responses parrots often engage in when they are in the wild.

Researchers observed multiple instances of birds appearing to mimic each other’s behaviors. Some would begin grooming themselves after watching a bird on the other end of screen do so. Other times, the birds would “sing” in unison. In one video, a colorful parrot can be seen eagerly waiting for a call to connect. A large white bird eventually appears on the other end of the call, which results in the red bird banging its head and chirping in excitement. In another case, a male macaw video-calling with a fellow macaw would let out the phrase “Hi! Come here!” If the second bird left the screen, the vocalizing bird would quickly ring a bell, which the caretakers interpreted as the bird asking his friend to return to the screen.

“Some strong social dynamics started appearing,” Northeastern assistant professor Rébecca Kleinberger said in a statement.

Parrots prefer calling real birds over pre-recorded video

Interestingly, parrots included in the study appeared substantially less interested in video calls if they featured pre-recorded video of other birds. A related study published by University of Glasgow researchers show the parrots strongly preferred to chat with other parrots in real time. Over the course of six months of observation, the parrots spent more time engaged in the calls with real birds than with the pre-recorded videos. Those findings suggest the birds weren’t merely being existed by the presence of a screen. Rather, the actual communication with another living bird plays an important role.

Combined, the birds in the study spent 561 minutes in love calls with other birds compared to just 142 minutes interacting with the pre-recorded videos. The birds’ caregivers reinforced that point and told researchers they appeared more curious and engaged when a live bird was on the other end of the call.

“The appearance of ‘liveness’ really did seem to make a difference to the parrots’ engagement with their screens,” Douglas recently wrote. “Their behavior while interacting with another live bird often reflected behaviors they would engage in with other parrots in real life, which wasn’t the case in the pre-recorded sessions.”

Researchers are hopeful these findings could one day be used to help parrots improve their socialization. And while some of the parrot caretakers surveyed noted the steep learning curve to train the parrots, every one of them said the project was worthwhile once concluded. An overwhelming 71.4% of the caretakers in the video calling study said their birds had a very positive experience. By contrast, none of them described the experience as negative. One caretaker in particular claimed her pet “came alive during the calls.”

“We’re not saying you can make them [the parrots] as happy as they would be in the wild,” Kleinberger said. “We’re trying to serve those who are already [in captivity].”