Thanks to over three decades worth of work by countries around the world in keeping ozone-damaging chemicals out of the atmosphere, Earth’s ozone layer is on track to recover.

According to the United Nations’ 2022 Scientific Assessment Panel to the Montreal Protocol on Ozone Depleting Substances, 99 percent of banned ozone-depleting substances, including chlorofluorocarbons, have been successfully phased out.

[Related: From the archives: NASA dispatches drone to help rescue the ozone layer.]

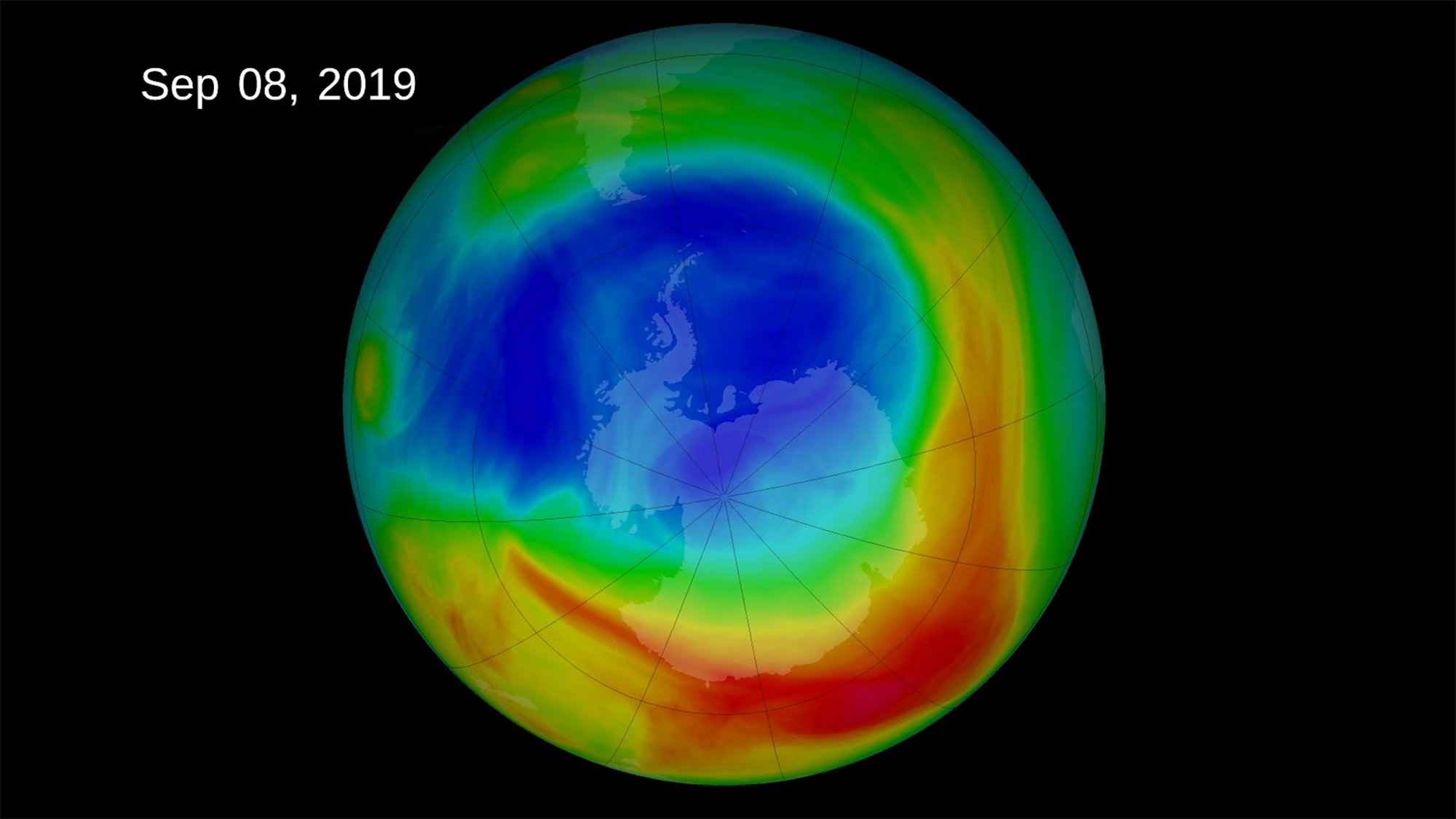

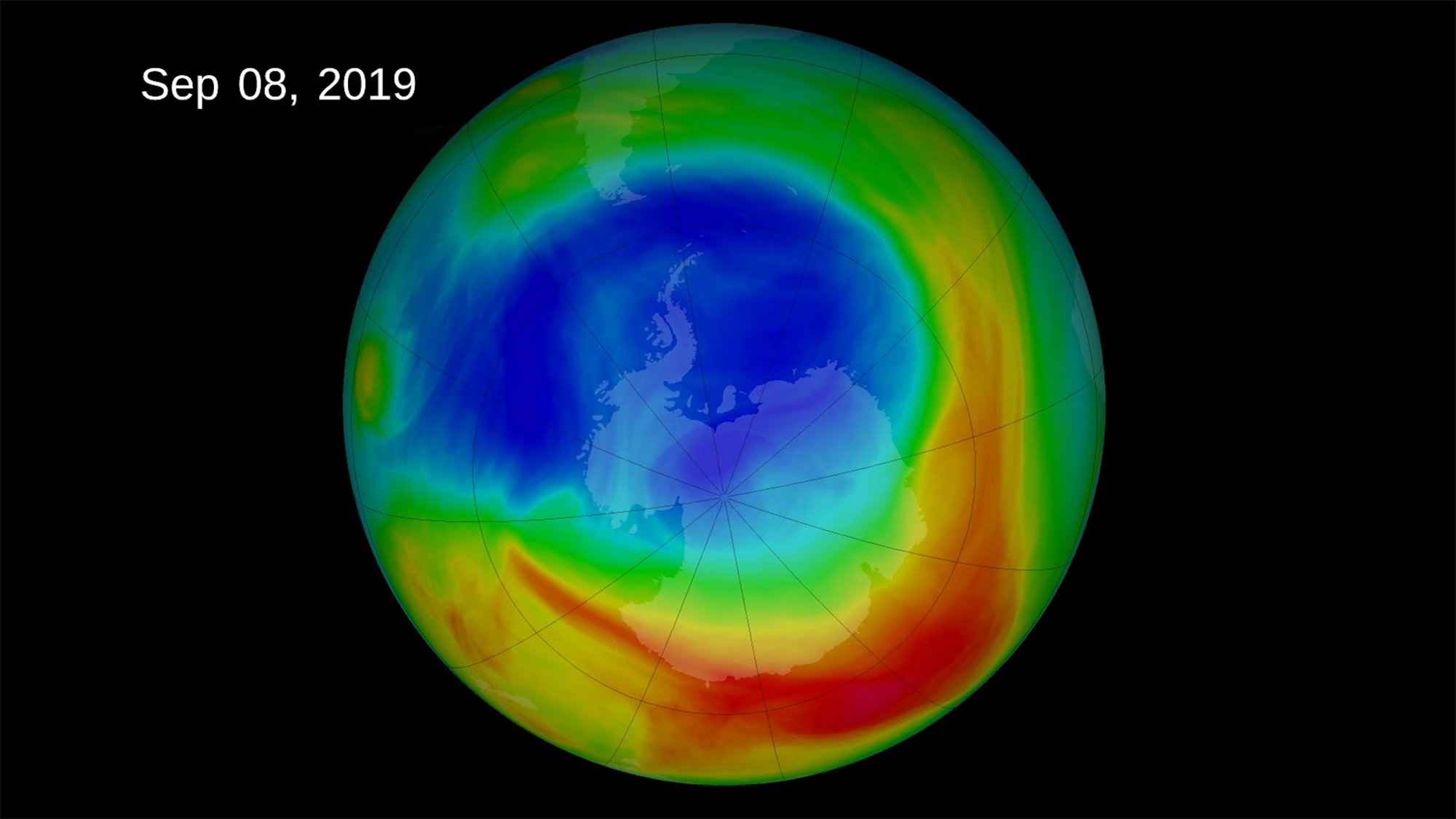

If current policies remain, Earth’s ozone layer is expected to recover to values seen before ozone holes were were detected by about 2066 over the Antarctic, 2045 over the Arctic, and as soon as 2040 for the rest of the world. The Antarctic ozone hole continued expanding until the year 2000. Meteorological conditions between 2019 and 2021 caused some variations in its size, but the layer has still healed overall over the past 22 years.

In the 1980s, scientists discovered a gaping hole in the ozone layer. Two years later, 46 countries signed The Montreal Protocol, promising to phase out the use of over 100 synthetic chemicals that deplete Earth’s ozone layer. This deal later became the first UN treaty to achieve universal ratification.

“That ozone recovery is on track according to the latest quadrennial report is fantastic news. The impact the Montreal Protocol has had on climate change mitigation cannot be overstressed. Over the last 35 years, the Protocol has become a true champion for the environment,” said Meg Seki, executive secretary of the United Nations Environment Programme’s Ozone Secretariat, in a statement. “The assessments and reviews undertaken by the Scientific Assessment Panel remain a vital component of the work of the Protocol that helps inform policy and decision makers.”

Located in the stratosphere, the ozone layer protects all living things on Earth from harmful levels of ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun. Synthetic chemicals like the chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), used to make aerosol sprays, solvents, and refrigerants can destroy ozone, and caused Earth’s ozone layer to deplete during the 20th century. Ultraviolet rays can cause painful and dangerous sunburns and even damage DNA, increasing the risk of problems like skin cancer.

While the depletion of the ozone layer is not a major cause of climate change, research shows that these global efforts to save it are beneficial in the fight against climate change.

[Related: The US ban on hydrofluorocarbons is a climate game-changer.]

In 2016, an amendment to the Montreal Protocol (called the Kigali Amendment) that required the phase out of the production and consumption of some hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) was added. While HFCs do not directly deplete ozone, they are powerful climate change gasses which can accelerate warming. An uptick in CFC use was detected in 2018 and tracked to China, but that was quickly fixed.

Scientists say that the Kigali Amendment is estimated to avoid 0.5–0.9°F of warming by 2100, not including contributions from HFC-23 emissions.

“Ozone action sets a precedent for climate action. Our success in phasing out ozone-eating chemicals shows us what can and must be done – as a matter of urgency – to transition away from fossil fuels, reduce greenhouse gases and so limit temperature increase,” said World Meteorological Organization Secretary-General Petteri Taalas, in a statement.