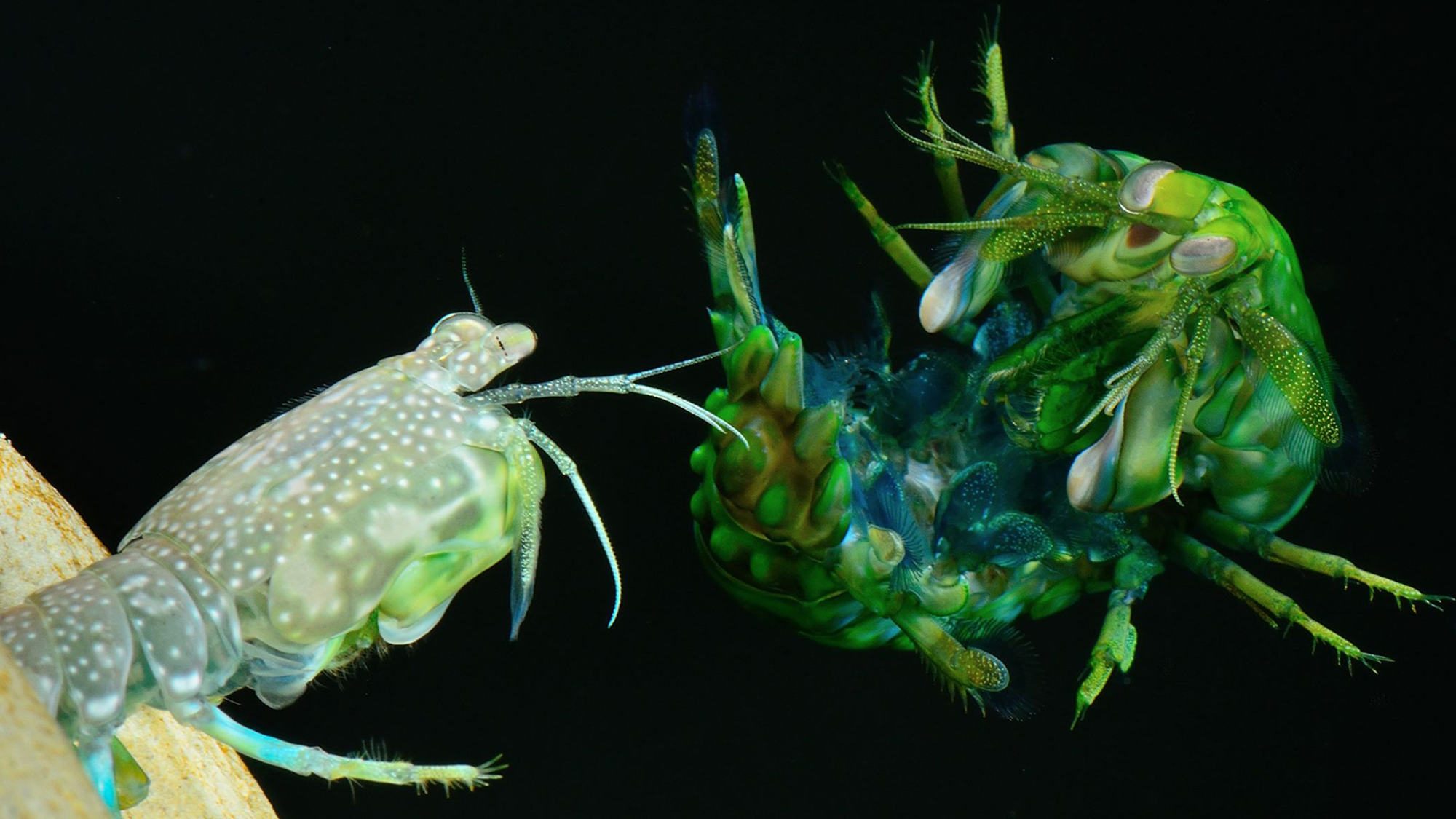

With their impressive eyes, Herculean strength, and punches with the force of a 22-caliber bullet, mantis shrimp are some of the ocean’s most impressive tiny wonders. These sucker punches are used on animals like worms, squid, and fish that they are preying on, predators, and each other.

New research found that their shells make a decent shield against rival mantis shrimp–absorbing an additional 20 percent of the shock. The findings are described in a study published May 9 in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

“In mantis shrimp competitors exchange bullet-like hits on each other’s armored tail plates, or telsons, during fights over shelters,” study co-author and University of California, Santa Barbara ecologist Patrick Green said in a statement.

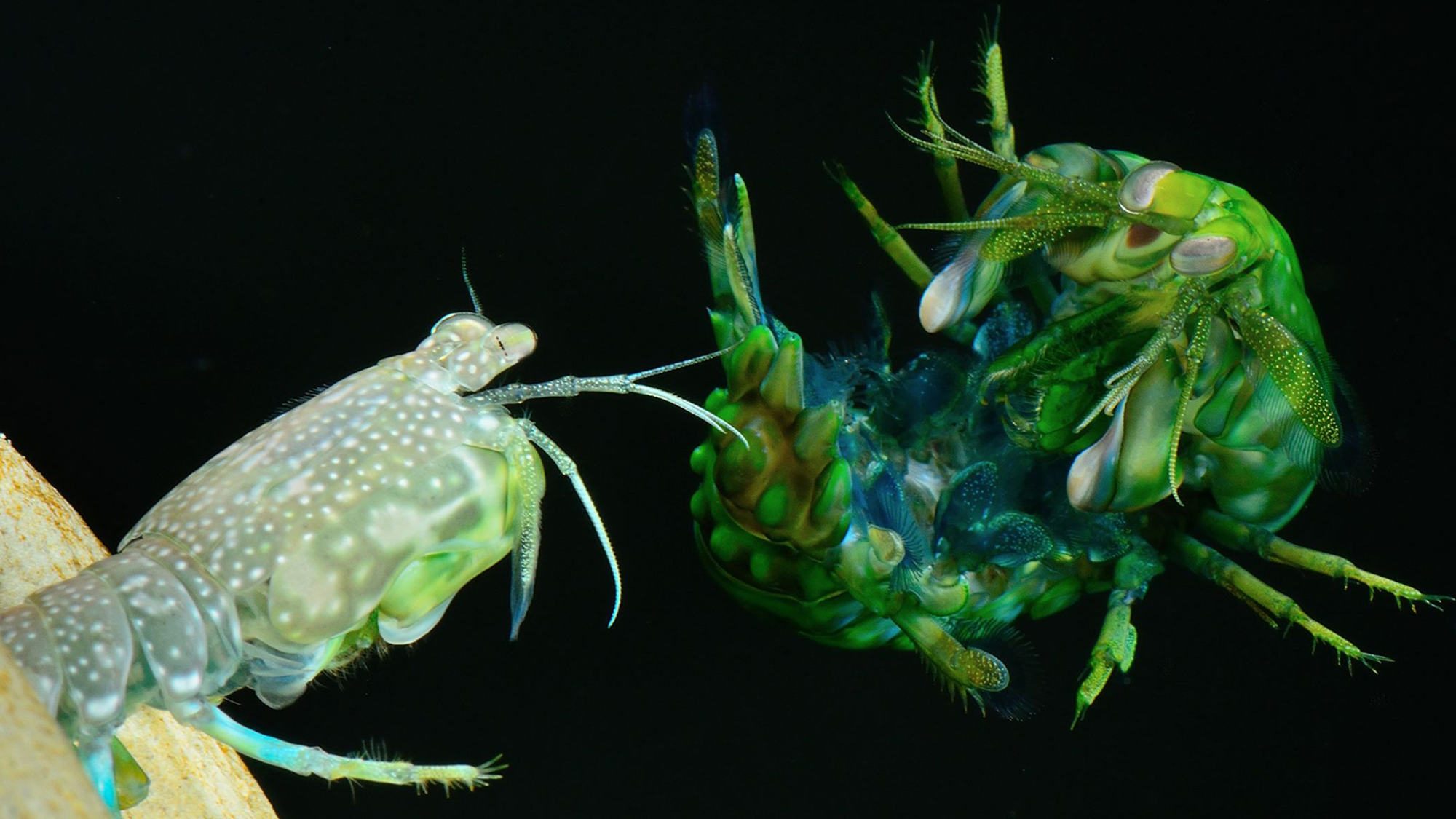

Earlier studies found that mantis shrimp have exoskeletons that are resilient to strikes. They take in some of the impact like shock absorbers or a punching bag. However, these studies looked at their armor in a lab setting. In more natural rights, territorial mantis shrimp coil up their tails in front of their bodies and use them like a shield.

[Related: Baby mantis shrimp punch their prey with superior strength.]

In the study, Green was curious how the use of the tail changed how they received impacts. Green introduced pairs of these crustaceans and recorded their fighting. “They almost immediately started hitting each other,” he said.

Green captured footage of this fighting at 30,000 to 40,000 frames per second–about 1,000-times faster than a regular camera. Analyzing how their appendages moved before and after they made contact allowed him to calculate just how much energy is given by each punch. This and the movement of their tails before and after impact, indicated how much energy the tails dissipated from each strike.

Using their tough tail plates in a coiled way appears to help the mantis shrimp to dissipate more energy than their armor can absorb alone.

“It made logical sense to me that holding your armor off the ground should let you dissipate more energy,” Green said. “Think about a boxer moving with a punch that they receive.”

[Related: These crustaceans take cheap shots at rivals by growing enormous claws.]

However, accounting for the movement of their appendages versus both appendages and tails together, the results were different. Green plans to continue studying mantis shrimp armor and fighting to see what role their various shapes and sizes play. Different mantis shrimp species also vary in how much they fight and there could be a correlation between behavior and morphology.

“When we try to understand how animals contend with impacts, we should think about both the structures they use (like armor) and also how they use those structures,” Green said. “This study helps us connect behavior and morphology, so we can better understand how animals navigate their fights.”