Mammals are defined by how and what we eat every single day of our lives. It is no wonder then that jaws are a pretty big deal for our anatomy and biology. Now, a 225-million-year-old fossilized jaw joint appears to represent the oldest example of a type of joint that has helped make mammals what they are today. This skeletal structure reveals that similar structures may have evolved in early mammal species that are not closely related. This jaw also could have evolved roughly 17 million years earlier than paleontologists previously believed. The jaw-dropping details are described in a study published September 25 in the journal Nature.

[Related: We’re one step closer to identifying the first-ever mammals.]

We are what we eat

In addition to being vertebrates with body hair and providing milk for their young, a hinge-like jaw joint is one of the key features of being a mammal. Among other vertebrates, modern mammals are also exceptional for their ability to control jaws for more precise chewing. This makes fossils of early mammalian jaws essential clues to how this unique jaw set up arose over the course of evolution.

“Mammals are defined by what mammals eat with–jaws and teeth,” study co-author and University of Chicago paleontologist Zhe-Xi Luo tells Popular Science. “Mammalian jaw hinge is unique in that the tooth-bearing dentary bone is directly connected to the jaw hinge so mammals can take more forces from chewing and biting, than other vertebrates with jaws.”

Modern mammals evolved from within a larger group of animals called cynodonts. Their early forms had a jaw joint that was made of two completely different bones–the quadrate of the skull and the articular in the lower jaw and the quadrate in the skull. Paleontologists previously believed that all mammal sister-groups, and many of their jaw characteristics were mammal-like, but the jaws fossils hadn’t been reexamined using micro-computed-tomography (CT) scans.

Meet Brasilodon and Riograndia

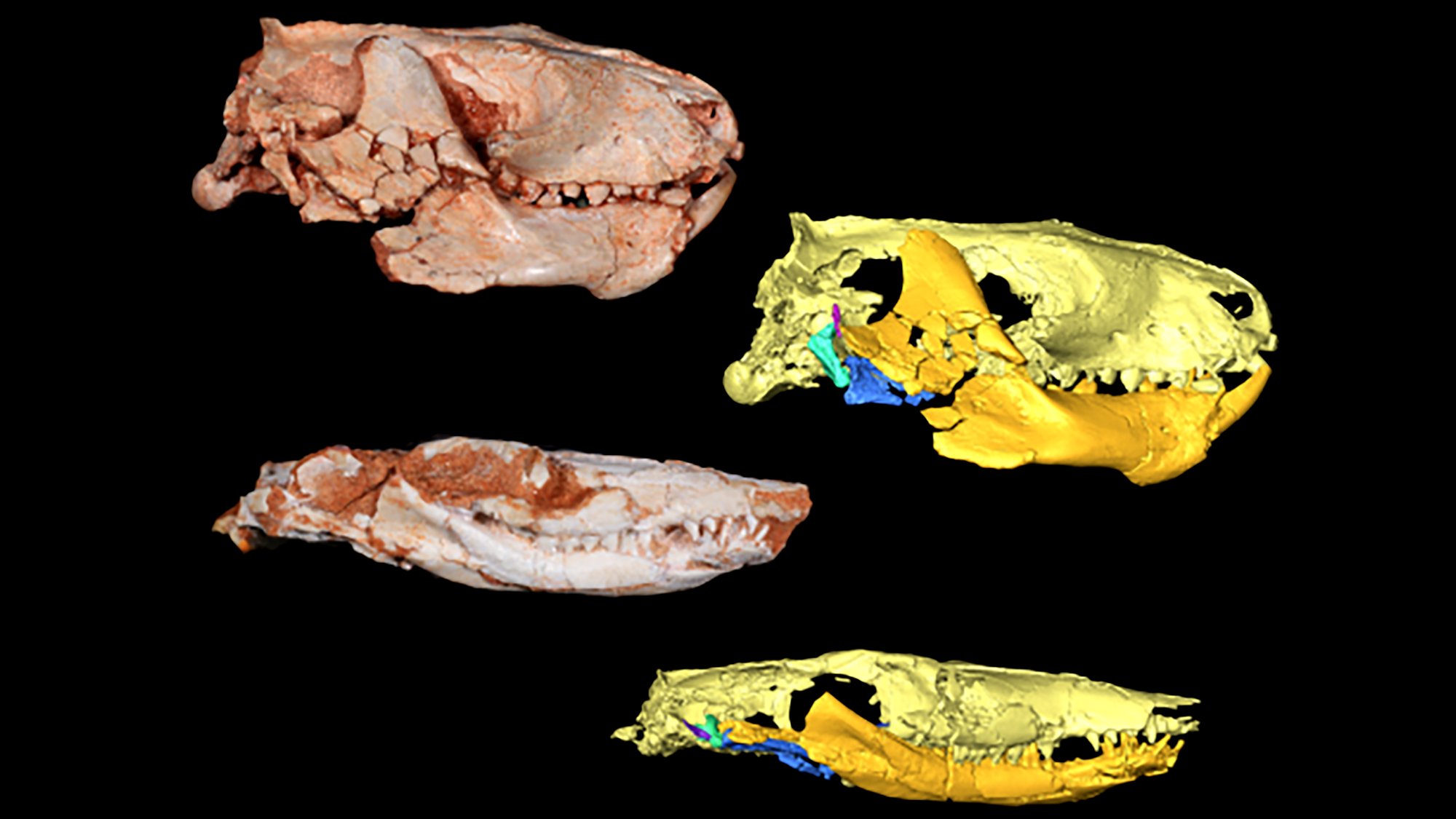

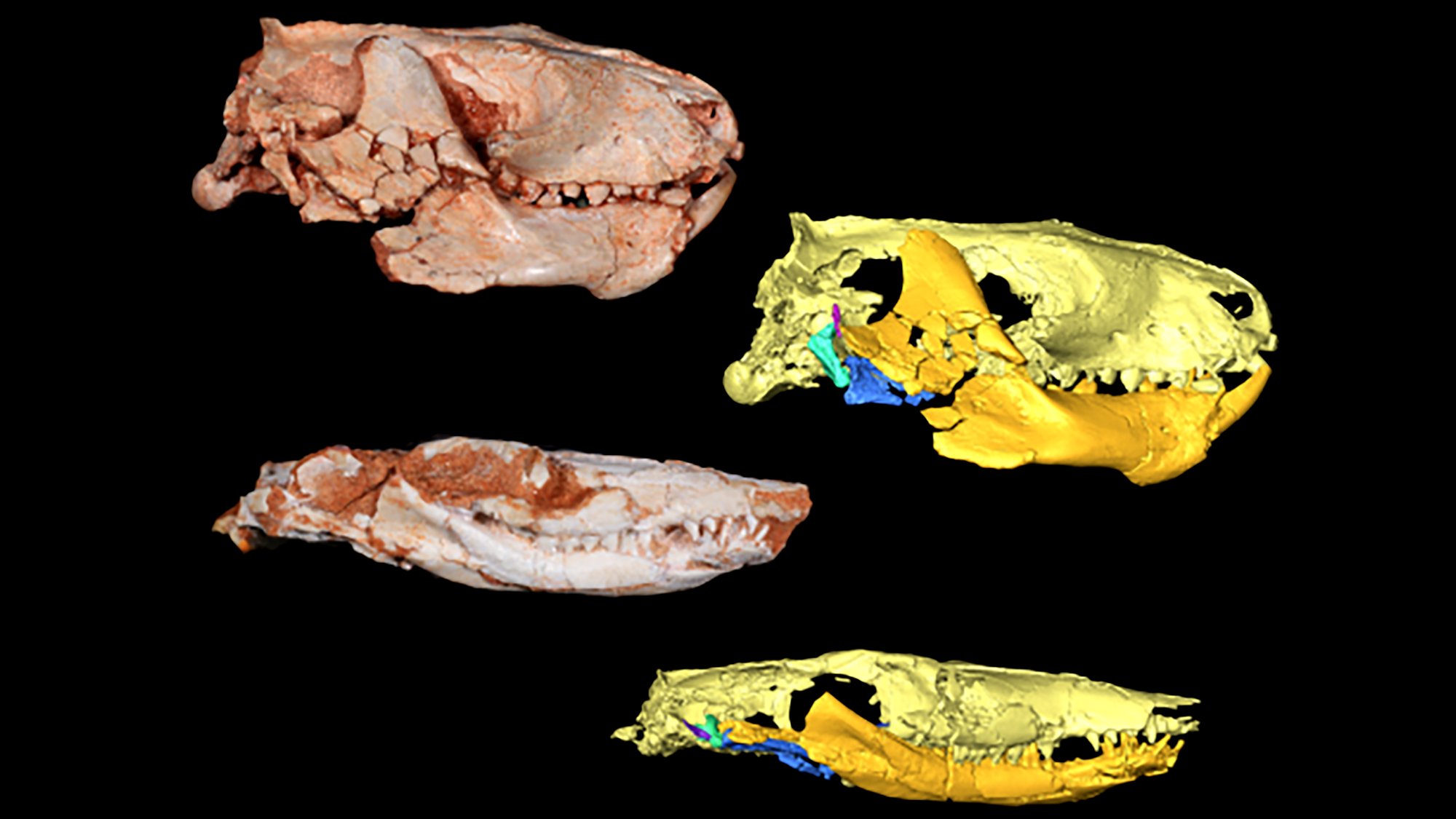

In the new study, the team used some roughly 225-million-year-old fossils uncovered in present-day Brazil.

“These amazing fossil sites date back to the Triassic period where important animal groups like mammals, dinosaurs, crocodilians, turtles, lizards, and more were first evolving, making them really important for understanding the origin of those groups and modern ecosystems in general,” study co-author and University of Bristol paleontologist James Rawson tells Popular Science. “The quality of the fossils is also incredible, many are preserved intact and also in 3D!”

The specimens are of two extinct cynodont species–Brasilodon quadrangularis and Riograndia guaibensis. Both species were tiny, at about six to 11 inches long. They likely spent a good deal of time in burrows hiding from predators, similar to small living mammals. Brasilodon’s teeth suggest that it likely would have eaten insects and other small animals. Riograndia had more rodent-like incisors and leaf shaped postcanine, which indicate it would have eaten more plant material.

“Brasilodon and Riograndia really stand out because they are very closely related to mammaliaforms, the group that includes modern mammals and their ancestors,” says Rawson. “And so their lifestyle and anatomy gives us valuable clues into how mammals evolved their most defining features.

[Related: Baby teeth reveal surprisingly long lifespans of small Jurassic mammals.]

The team used CT scanning to reconstruct the jaw joint anatomy of both animals. Riograndia’s jaw joint appears more similar to modern mammals, despite Brasilodon being more closely related to living mammals. This jaw joint called the dentary–squamosal contact in Riograndia likely evolved entirely separately and around 17 million years earlier.

That this feature evolved earlier and more than once reveals a much more complex picture of jaw evolution in mammals.

“Humans are mammals. We chew and bite to eat,” says Zhe-Xi. “Our life depends on our feeding function, which requires our jaw hinge. Isn’t it interesting to reflect on our history: our jaw hinge that made us the mammals unique among vertebrates actually started out some 225 million years, during the time when mammals and their relatives lived in the dark Age of Dinosaurs.”