This article was originally featured on Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

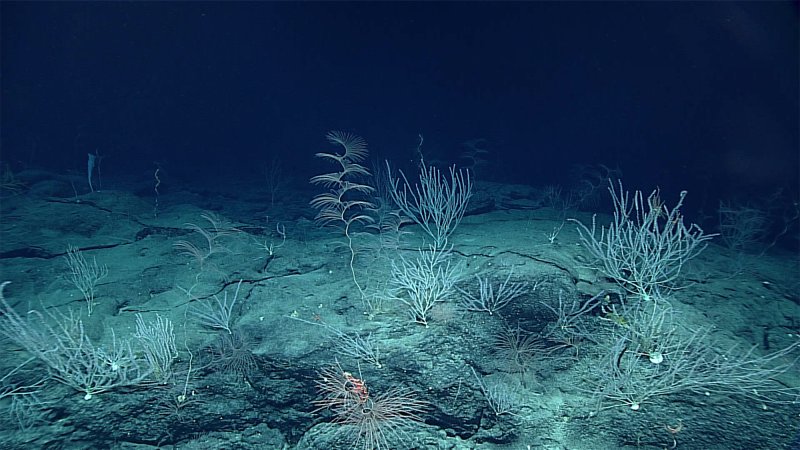

In 2013, a huge marine heatwave known as the Blob hit the northeast Pacific Ocean. Temperatures soared to dangerous new highs, killing millions of marine animals and disrupting the broader ocean ecosystem in ways that have yet to—and may never—return to normal. Although the Blob officially ended in 2016, similar heatwaves have flared several times since. Scientists are still trying to unpack what exactly caused the Blob and its ilk, but a recent study highlights just how connected the global climate really is. This research, led by Hai Wang, an atmospheric scientist at the Ocean University of China, suggests environmental progress in China—aimed at clearing up the country’s substantial air pollution—inadvertently contributed to the extreme sea surface temperatures that cooked the Pacific coast from Alaska to California.

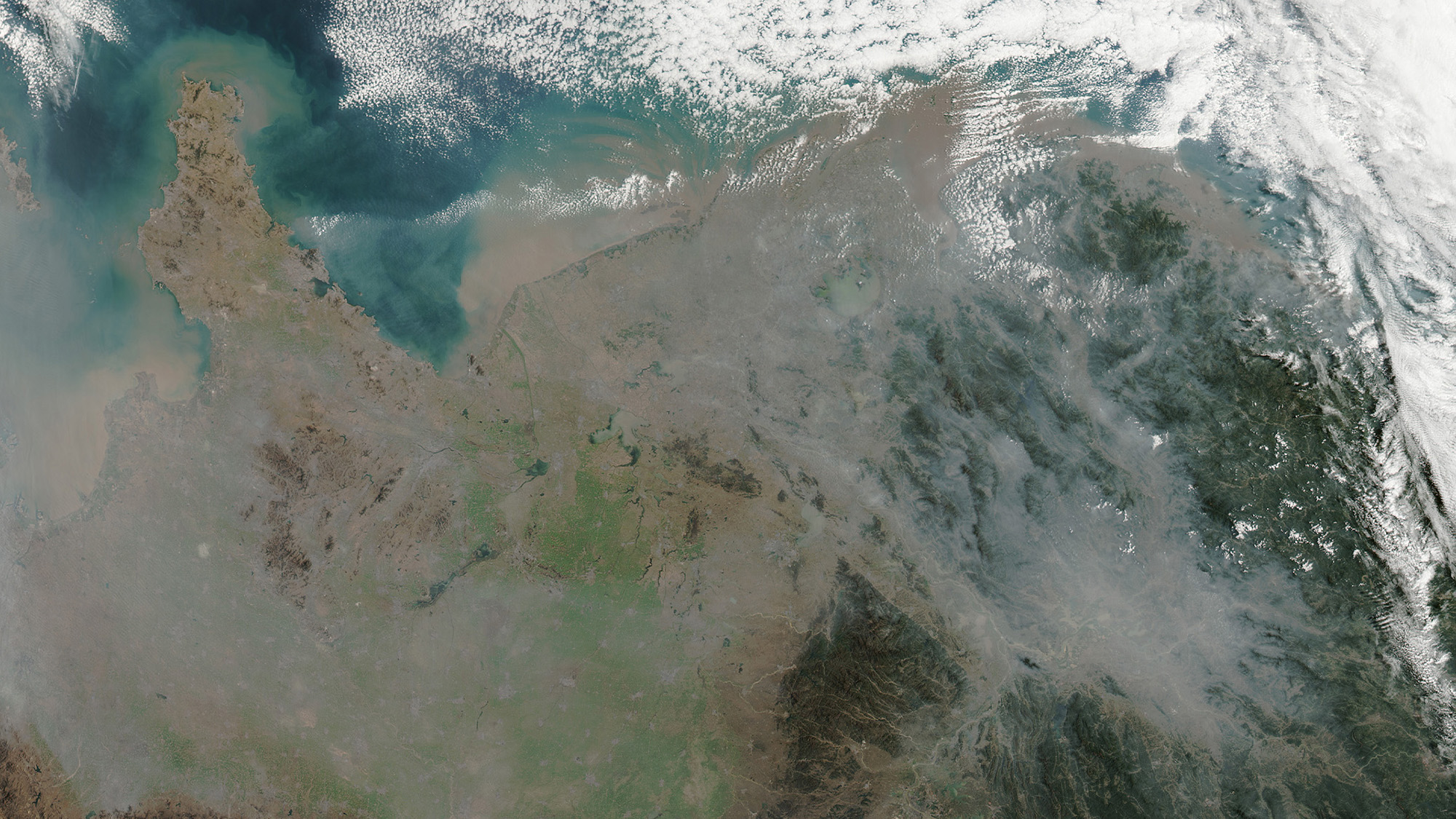

Since the early 2010s, China has tackled its aerosol emissions problem aggressively. Two decades ago, Chinese residents faced horrendous air quality, with concentrations of fine particulate matter (PM)—particles with a diameter smaller than 2.5 microns, known as PM 2.5—five to 10 times higher than the safe air quality guidelines published by the World Health Organization. These tiny particles, mainly produced by burning fossil fuels, irritate peoples’ throats and lungs, trigger asthma attacks, and drive up hospital admissions for cardiovascular issues. Extended exposure can increase the risk of stroke, heart disease, asthma, and lung cancer.

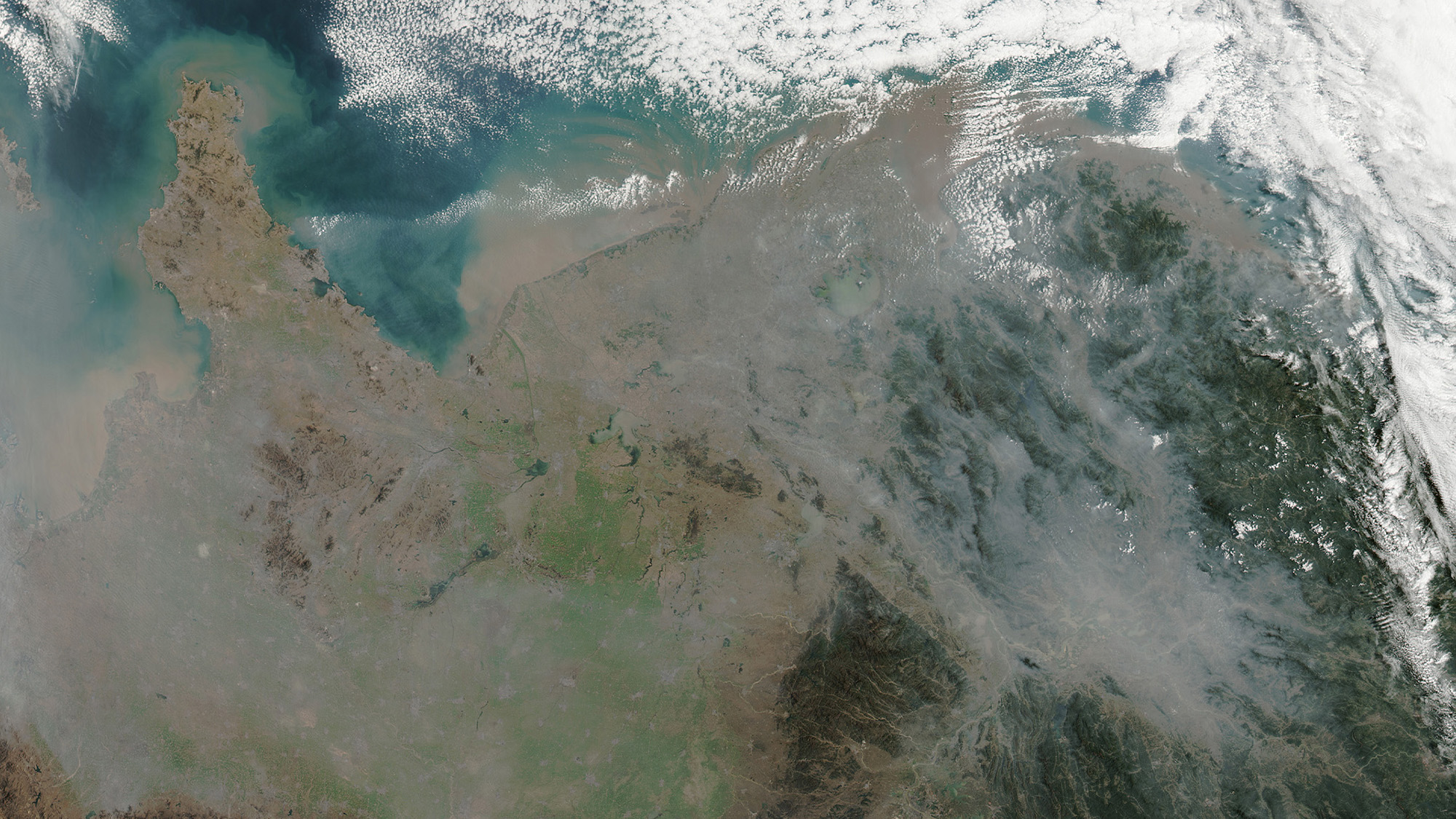

Between 2010 and 2017—and especially after 2013, when China adopted its new clean air action plan—the country’s PM 2.5 pollution level fell by 35 percent. But the waning toxic haze sparked a series of atmospheric changes in China and beyond.

Fine aerosol pollution increases cloud cover while also blocking and scattering heat from the sun. This cools the Earth’s surface and can even mask some of the warming caused by burning oil, gas, and coal. Removing the pollution, then, had the opposite effect, says Wang: declining aerosol concentrations caused the air over East Asia to heat up, triggering a cascade of atmospheric changes that helped heat the northeast Pacific.

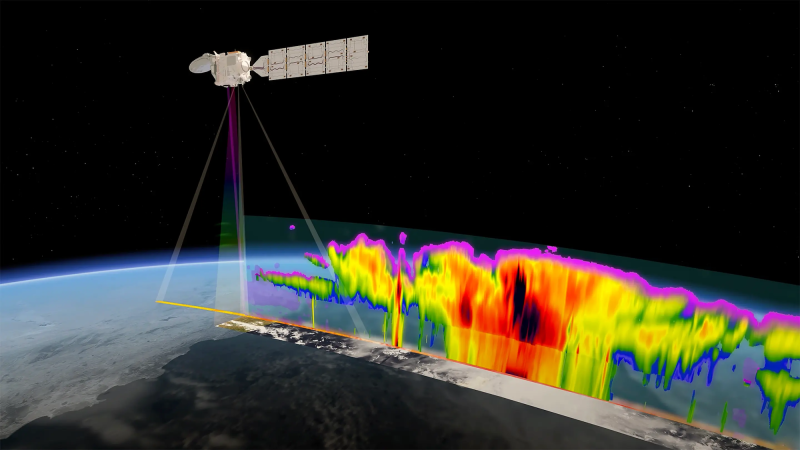

On a broad level, scientists understand how extreme marine heatwaves, such as the Blob, work. If the surface winds over the northeast Pacific stall for some reason—because of a stagnant atmospheric pressure system, for instance—the ocean loses some of its ability to shed excess heat into the atmosphere. This alone causes the water to warm, but it also kicks off a series of changes that exacerbate the issue. Lower wind speeds, for example, reduce mixing in the upper ocean, which usually brings cooler water from the deep up to the surface. Higher sea surface temperatures also reduce cloud cover by destabilizing the lower atmosphere, allowing more sunlight to hit and further heat the ocean.

Global warming caused by anthropogenic carbon emissions has been raising sea surface temperatures across the globe, making heatwaves like the Blob more likely. Year-over-year climate variability and longer-term ocean fluctuations can also account for some of the extreme warming that caused the Blob. But so can China’s drawdown of its dangerous aerosol emissions.

Specifically, Wang’s study shows how decreasing aerosol concentrations in China led to increased temperatures in East Asia. This, in turn, helped raise atmospheric pressure. This high-pressure system then intensified a low-pressure system over the Bering Sea, ultimately causing the surface winds over the northeast Pacific to drop, kicking off the rest of the warming cycle.

“Much like when we drop a rock and send waves across a pond, temperature changes in one region can also ripple across the atmosphere,” says Wang.

Wang is careful to note that while these atmospheric changes created a warmer baseline condition that contributed to the Blob’s formation, he stresses that China’s aerosol policies did not cause the Blob.

Chris Smith, an expert in climate modeling at the University of Leeds in England, says Wang’s study cleverly shows that the only climate models that can recreate the Blob are the ones that include China’s pollution reductions. But he agrees that the Blob was the result of “lots of different factors that all push in the same direction”—notably greenhouse gas emissions.

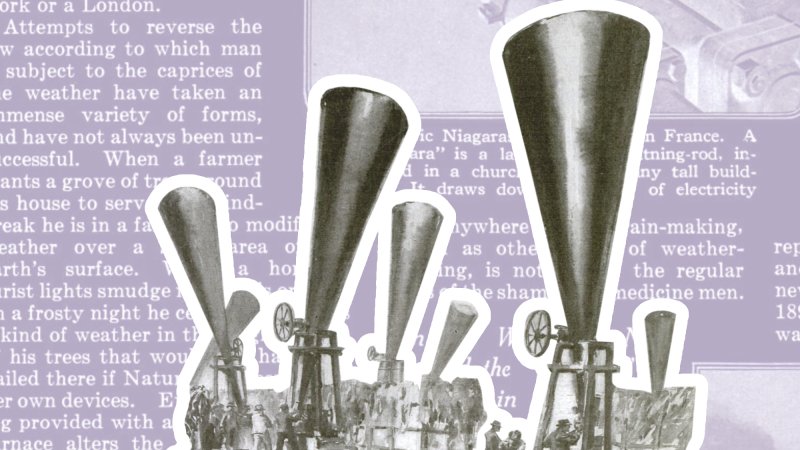

Wang says that while his work highlights how aerosol pollution can affect the weather—locally and halfway around the world—aerosol pollution is a public health hazard and should not be looked at as a way to manipulate the climate.

Indeed, a recent analysis shows that, globally, eight million people die every year because of air pollution, with aerosol pollution ranking as the second-leading cause of death in children under five—just after malnutrition. Smith also notes that the warming effect of reducing aerosol pollution will likely be short-lived.

Ultimately, Wang says, if we want to prevent future extremes like the Blob, the best way is to curb greenhouse gas emissions. Doing so is the only sure-fire “cure to mitigate long-term ocean warming, climate change, and the disasters they bring.”

This article first appeared in Hakai Magazine and is republished here with permission.