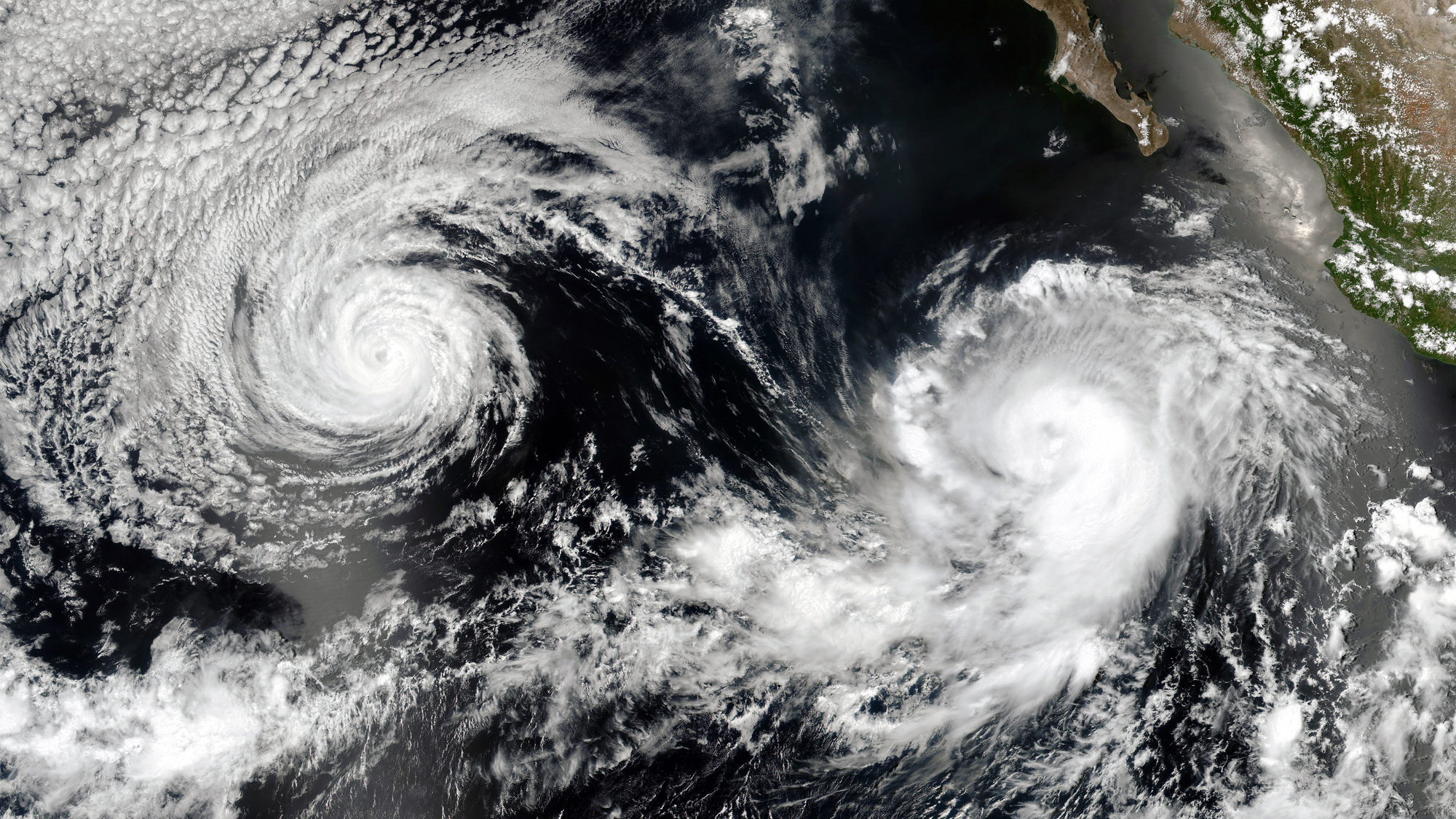

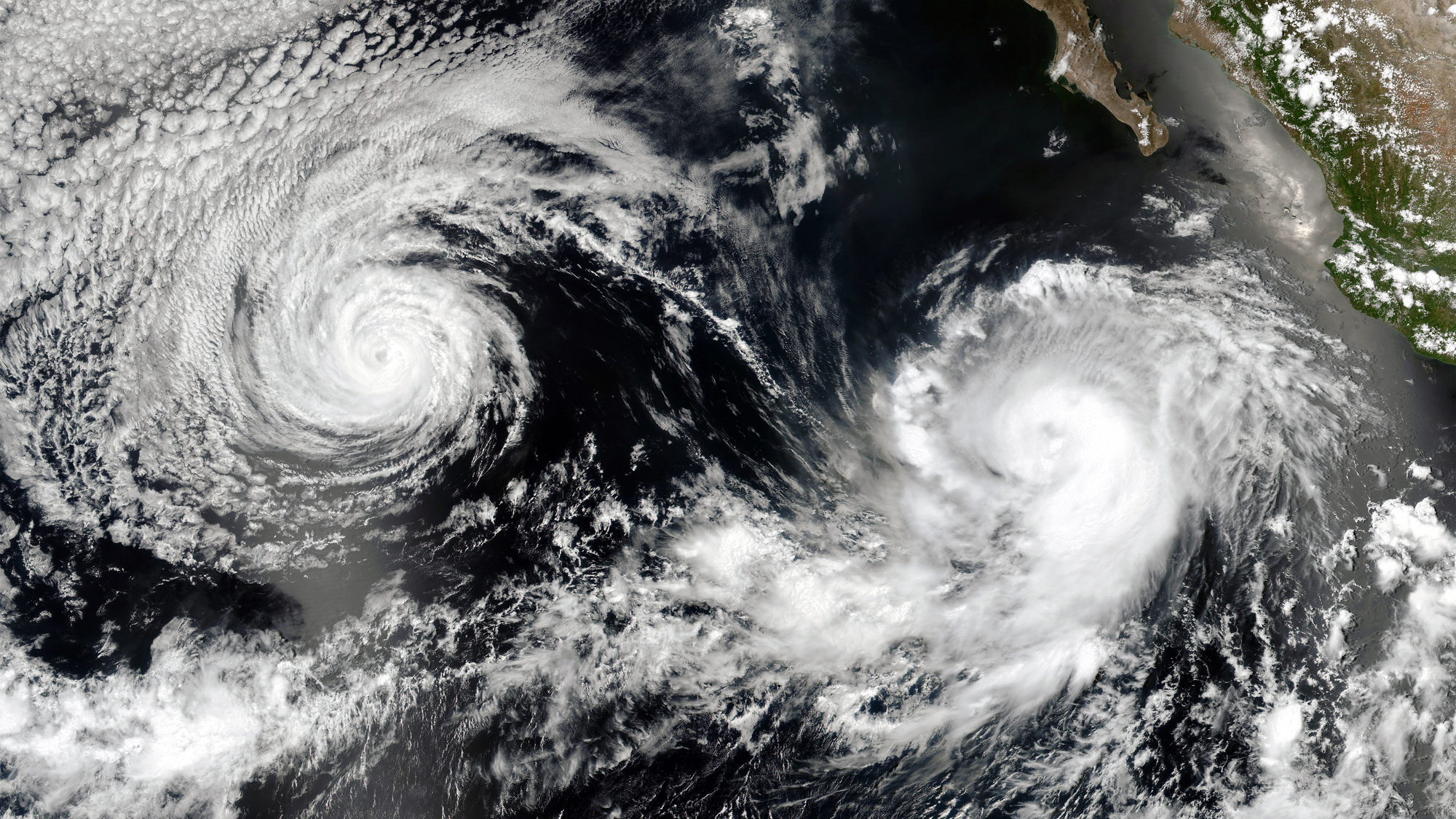

As ocean temperatures skyrocket to new records, hurricanes are getting stronger and more destructive. According to new research, the five-category Saffir-Simpson Windscale may need to add a Category 6 with a minimum wind threshold of 192 miles per hour and, potentially, even a Category 7.

[Related: What hurricane categories mean, and why we use them.]

According to a peer-reviewed research article published February 5 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), five storms within the past decade have had wind speeds so strong that they could be classified as a hypothetical Category 6 tropical storm. The Saffir-Simpson Windscale currently lists Category 1 storms as those with wind speeds between 74 and 95 mph. Category 5 storms as those with wind speeds 158 mph. Some of the five storms in recent years that could fit a hypothetical Category 6 had winds over 200 mph.

“Our motivation is to reconsider how the open-endedness of the Saffir-Simpson Scale can lead to underestimation of risk, and, in particular, how this underestimation becomes increasingly problematic in a warming world,” study co-author and climate scientist Michael Wehner of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory said in a statement.

Human-caused global warming has significantly increased both surface ocean and tropospheric air temperatures in the regions where tropical cyclones, typhoons, and hurricanes form. The warm temperatures provide extra energy for the storms with which to intensify. In August 2023, Hurricane Idhalia rapidly intensified from a Category 2 storm to a Category 4 storm, but eventually hit the Big Bend region of Florida as a Category 3 with sustained winds of 125 miles per hour. Tropical storms typically lose some steam as they hit land and are no longer over the warm water that they use for fuel. However, some storms like 2017’s Hurricane Harvey can produce so much rain that they stall and generate their own mini-oceans that they use to keep going.

When Wehner and colleagues performed a historical data analysis of hurricanes between 1980 and 2021, they found five storms that would fit into a Category 6 that have all occurred in the last nine years. It includes 2015’s Hurricane Patricia, which was the most powerful tropical cyclone that lashed Mexico with winds up to 215 mph. The other storms include Typhoon Haiyan in 2013, Typhoon Meranti in 2016, Typhoon Goni in 2020, and Typhoon Surigae in 2021.

The team determined this hypothetical upper boundary of 192 mph for Category 5 hurricanes by looking at how the wind speeds of lower-category storms have expanded over time. High-resolution climate models also show that storms with faster winds are increasing with global temperatures.

If we continue to emit carbon into the atmosphere at current rates, hypothetical Category 7 storms could also emerge. “It certainly is theoretically possible if we keep warming the planet,” article co-author and climate scientist James Kossin at the First Street Foundation told New Scientist.

The team also found that with every two degrees Celsius of global warming above pre-industrial levels, the risk of one of these Category 6 storms increases by up to 50 percent near the Philippines and doubles in the Gulf of Mexico. The highest risk of these storms is in parts of Southeast Asia and Australia, the Philippines, and in the Gulf of Mexico.

[Related: Atlantic hurricanes are getting stronger faster than they did 40 years ago.]

“Even under the relatively low global warming targets of the Paris Agreement, which seeks to limit global warming to just 1.5°C [2.7 degrees Fahrenheit] above pre industrial temperatures by the end of this century, the increased chances of Category 6 storms are substantial in these simulations,” said Wehner.

The authors are not calling for the addition to the scale just yet, but rather want it to raise awareness about the risk that major hurricanes fueled by global warming may cause. They also express that a warning scale solely based on wind speeds that does not include potentially more deadly flooding and storm surge is flawed, and may need an update due to climate change. Hurricane Sandy was just barely a Category 1 when it hit New York and New Jersey in 2012, but still killed 43 people in New York City alone and at least 125 in the United states. A 2021 study found that the effects of climate change increased Sandy’s roughly $70 billion in damage by about $8 billion.

“Our results are not meant to propose changes to this scale, but rather to raise awareness that the wind-hazard risk from storms presently designated as Category 5 has increased and will continue to increase under climate change,” Kossin said in a statement.