For the majority of people suffering from depression, medication can help ease symptoms. Antidepressants aren’t perfect, and it can take a few tries to identify the best drug for each person, but in most cases, they work. However, somewhere between 10 and 30 percent of people don’t respond to any treatment.

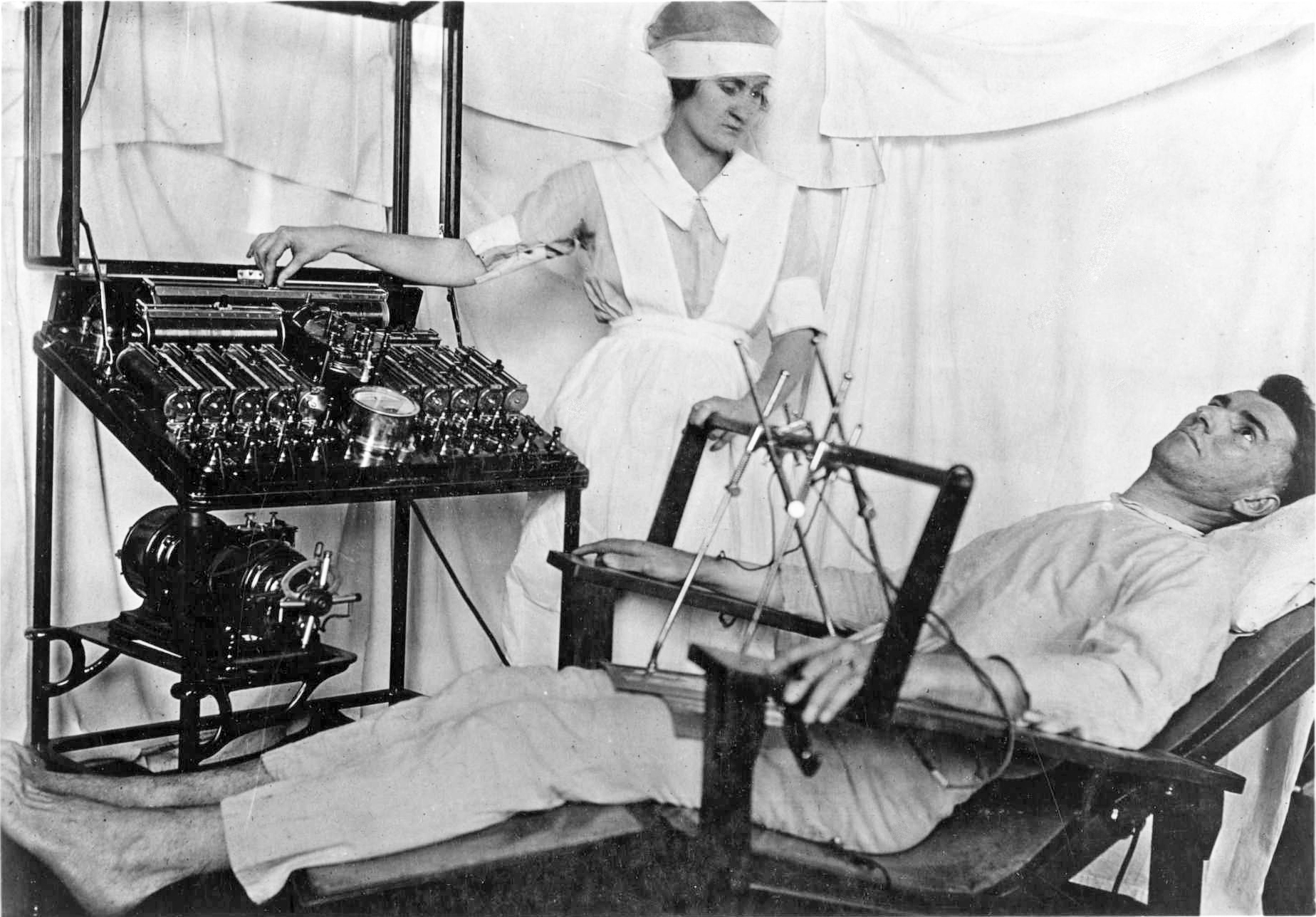

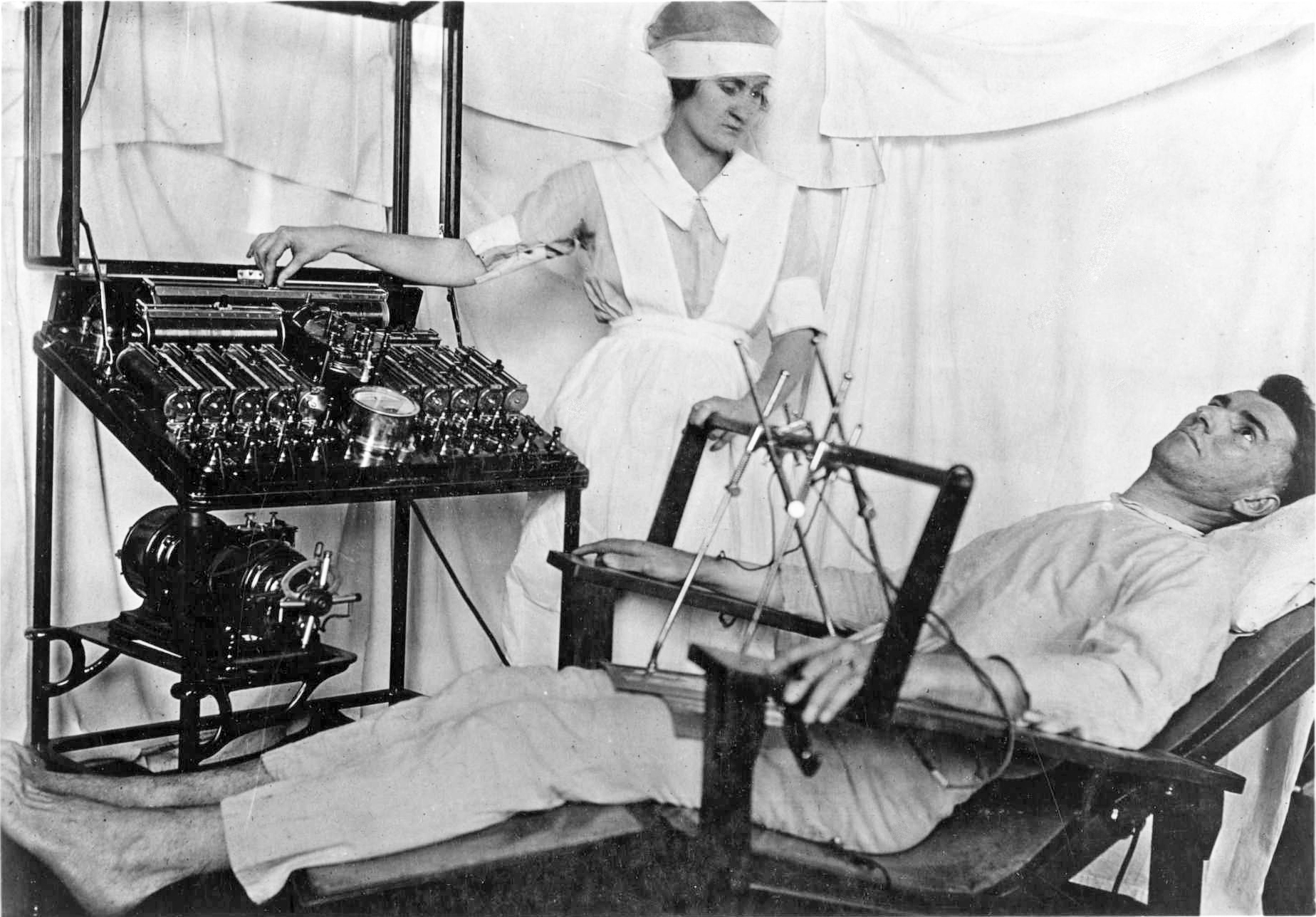

One option for patients in that group is a treatment called electroconvulsive therapy, or ECT. It’s colloquially known as shock therapy—but this isn’t the torture vividly portrayed in movies like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Today, ECT is performed under anesthesia, and the electric current is targeted and controlled. It’s a misconception that the procedure is scary and physically extreme, says Amy Aloysi, the director of the ECT service at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. She invites patients’ families into the room to watch the procedure, she says, to try and change that perception.

Like most therapies and medications, though, it’s doesn’t work for everyone, and can come with side effects and risks. ECT is well-accepted by the medical community, and it helps many patients who had struck out on treatment efforts in the past. Some physicians, though, feel strongly that it shouldn’t be used, and in rare cases, patients have reported bad experiences following the treatment.

Sue Cunliffe, a former pediatrician, wrote in a debate about whether ECT should still be used in medicine today in the British Journal of Medicine this week that she experienced slurred speech and major problems with memory and executive function after receiving ECT herself—significant enough that she was forced to leave her job. Such long-term side effects do happen, says Aloysi, but they’re rare, she says. It’s something she discusses with patients. “We definitely let people know that it can happen, and that we’re not 100 percent sure who it might happen to,” she says.

Aloysi has treated thousands of people using ECT, and says she hasn’t had any patients experience long lasting, life-impairing side effects.

The electric current delivered during ECT causes a brief, controlled seizure that causes change in the brain that alleviate the symptoms of depression. It’s unclear exactly how it works, though increases in proteins that help nerves grow, changes in neurotransmitter levels, and changes in brain regions (like the amygdala and hippocampus) involved in depression are all possibilities. It’s a misconception, Aloysi says, that ECT always causes physical damage to the brain. Most research shows that it doesn’t harm neurons or brain structures. In fact, it’s been shown to cause growth and activity in the brain: “There’s an increase in brain connectivity, and growth of hippocampal neurons,” she says.

Memory problems are common after courses of ECT, but those problems typically reverse not long after the treatment is delivered. “It’s manageable in the clinic, by adjusting the dose and frequency of ECT and other medications,” Aloysi says.

For the majority of patients, ECT works quite well. It’s the most effective way to treat treatment-resistant depression—about 50 to 70 percent of those who receive it see positive results. Patients who receive ECT are at a lower risk of readmission to a hospital within a month after release. The treatment works quickly—within days—unlike antidepressant drugs, which can take weeks to show effect. For severely depressed patients who might be suicidal, a fast-acting treatment can be key.

The lingering stigma and misconceptions around the treatment may make bad experiences with ECT stand out, and Aloysi says it’s important to talk about those cases. “We need to have conversations and look at the evidence,” she says. “We need to know what the effects are, and the rare effects.”

Patients who don’t respond to other treatments, though, might have to decide between undergoing ECT or continuing to live with depression, Aloysi says. “It’s a risk-benefit assessment, as with anything else,” she says. “But depression can be deadly.”