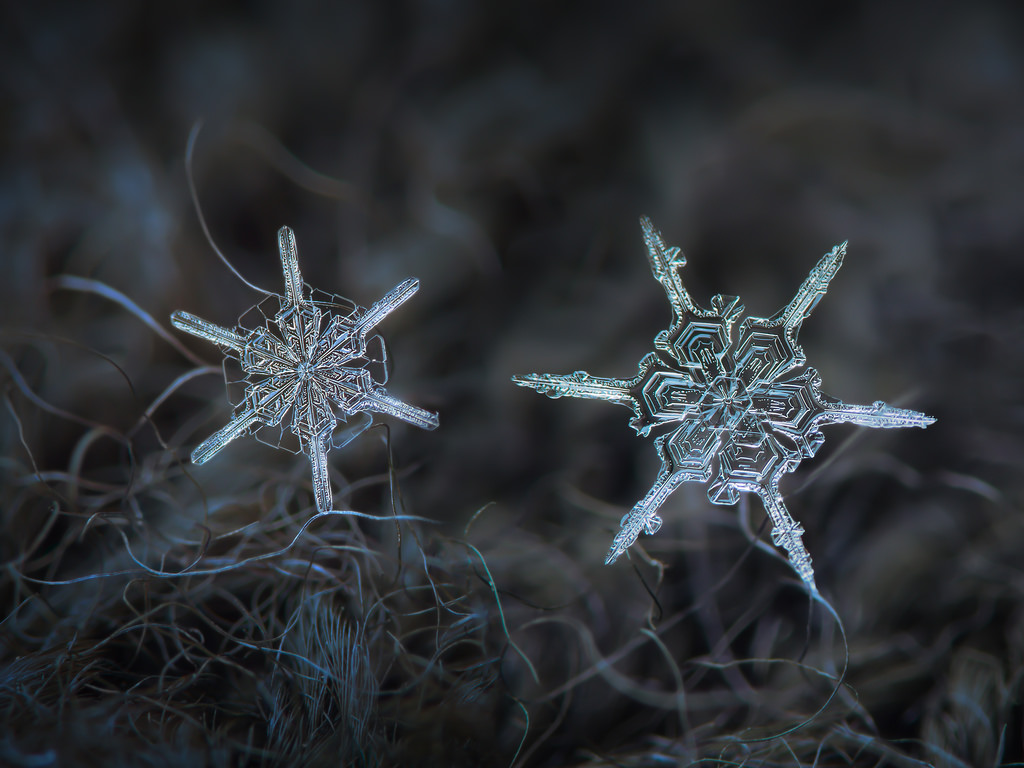

Snow can be soft and fluffy or stinging and icy; perfect for skiing or prone to melt. The difference lies in the shape of the flakes. They don’t all look like the kind you see in emoji. Researchers have classified as many as 108 types, but according to Kenneth Libbrecht, a physicist at the California Institute of Technology, you can pare them down to four broad categories: plates, columns, needles, and dendrites.

By re-creating snowflakes in a lab, Libbrecht and other scientists found that the keys to getting one shape instead of another are temperature and humidity. Snow crystals form when the humidity is so high that the air can no longer hold water. Then vapor condenses into droplets, which begin to freeze. Higher humidity lets the crystals take on more complex shapes—when the air is drier, snowflakes grow more slowly and take on simpler forms.

Light and flat, with six sides, plates are the one of the most common types of snowflake. Most snowfall contains a mix of small plates and other shapes. Libbrecht grows them in two sets of conditions: under 5°F or just below freezing.

Column-like snowflakes look like white hair when they fall on your sleeve, but up close, you can see more delicate details. This type tends to form at very cold temperatures, which makes them less likely to stick together. You’re more apt to find them in a sand-like snowfall.

Despite their simple appearance, needle snowflakes actually boast a more complex structure than columns or plates. At mid-range humidity, they grow as fishbone-like branches, forming long, thin columns. This structure lets the flakes pack together very tightly, so when they hit the ground, they create a perfect blanket for downhill skiing or snowball-making.

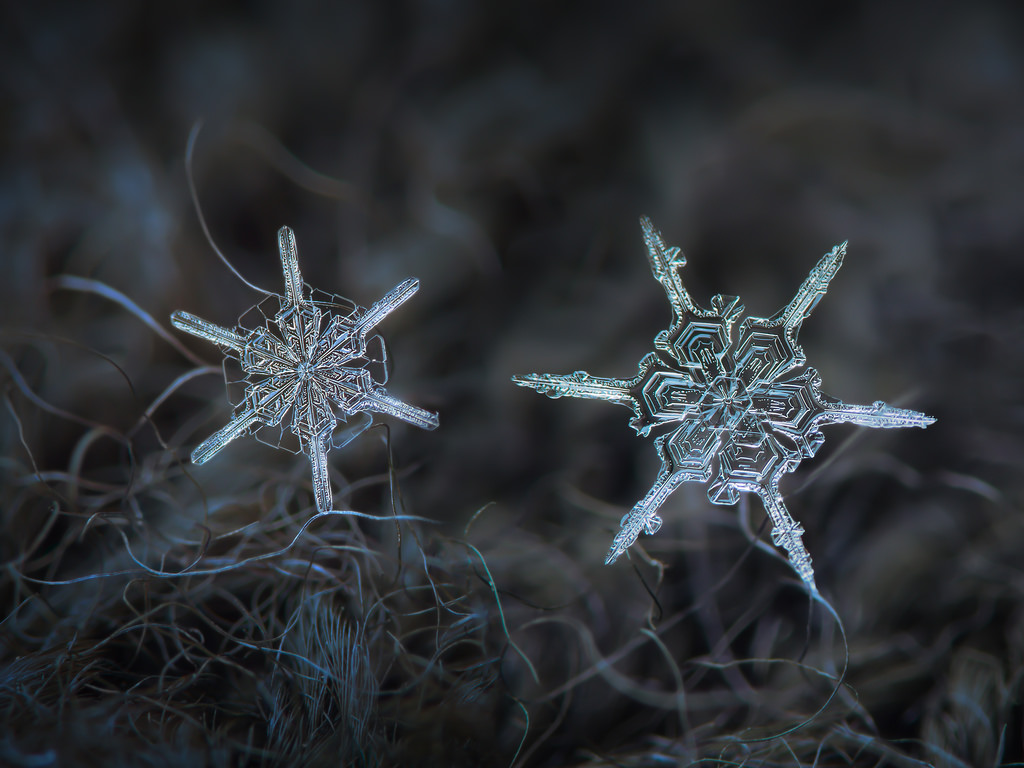

The secret ingredient for this intricate snowflake is relatively high humidity. With lots of moisture in the air, the vapor condenses more rapidly and the ice crystals branch more. Because dendrites have so many offshoots, they trap air in the snowpack, producing the fluffiest snow.

This article is a web exclusive for the July-August 2017 issue of Popular Science.