One of NASA’s greatest spacecraft will call it quits on September 15, 2017. The Cassini spacecraft has made countless discoveries during its sojourn to Saturn and its surrounding moons. It has also sent back nearly 400,000 images, many of which are purely spectacular, with surely more to come during the final months of the mission as Cassini explores new territory between Saturn and its rings.

In honor of the brave spacecraft, we spent hours sifting through the deluge of images to highlight some of Cassini’s best views from Saturn.

This impossible criss-cross pattern was created when a shadow of Saturn’s rings fell across the real ones.

A skirt of material around its middle makes this moon look like a dumpling.

Saturn has a lot of moons—53 at last count.

This image shows how heat is distributed across the gas giant and its rings.

Can you spot all three moons in this picture? The brightest is the icy Enceladus. Pandora appears below Enceladus, just above the rings, and Mimas hides in the lower right.

Titan looks a lot like Earth in this composite image. Peering through the haze, Cassini revealed that this large moon has lakes and streams of liquid methane on its surface, making it one of the top spots to search for alien life in our solar system.

That bright dot under Saturn’s rings is Earth, from 898 million miles away.

It looks chilly, but Enceladus has a salty ocean on the inside that may be capable of supporting life.

Small moons can have a big impact. Here, the 26-mile-wide Pan cuts a 200-mile gap through Saturn’s rings. It shares the road with two faint little ringlets.

The gravity of this five-mile-wide moon perturbs the orbit of the ring particles, carving ripples that gradually settle back down later.

Because the material on the inner edge of the gap (the right side) moves faster than the little moon, the waves occur in front of Daphis. The material on the outer edge of the gap moves slower, and therefore form behind Daphnis.

Cassini discovered geysers shooting out of Enceladus’ south pole, which may provide a window into the ocean within.

Some of the particles streaming from Enceladus’ south pole end up forming Saturn’s E ring, which is shown here—it’s the bright strip behind the moon.

To make this colorful image, Cassini shot three radio wavelengths at Saturn’s rings, and the distortion of those signals revealed how material is distributed throughout the rings. Scientists translated that data into colors: red indicates a region where there are no particles smaller than two inches in diameter; regions where there are particles smaller than two inches are shown in green; blue regions contain particles smaller than a third of an inch.

A colossal storm swept across Saturn’s northern hemisphere in 2010 and 2011, covering 500 times the area of the largest southern hemisphere storms. It eventually wrapped around the entire planet, stretching across 2 billion square miles.

False-color mosaics captured short-term changes in Saturn’s giant storm.

The sun brilliantly lights up Dione’s left half, while fainter illumination reflecting off of Saturn reveals the moon’s shadowy right side.

Enceladus has a groovy surface, marked by ridges, cracks, and troughs. It has relatively few craters—tectonic processes renew the crust and keep it looking young. Cassini captured this image from a distance of about 730 miles.

The sun glints off Titan’s northern polar seas. This moon is the only object in the solar system, besides Earth, that we know has liquid on its surface.

The Huygens probe eyes its landing site on Titan. After separating from Cassini, the probe landed on Titan and sent back pictures and data from its surface.

Saturn’s rings peek around the corner of this image of Enceladus’s icy surface.

Cassini revealed how strange Hyperion is in 2005. Scientists still aren’t sure what gives the moon its spongey structure.

Icy peaks stick up out of Saturn’s B ring, casting long shadows. These are some of the tallest structures in the ring system.

Cassini helped solve the mystery of why Iapetus is two-toned. Because the moon is tidally locked—meaning one side of it always faces Saturn—another side of it is constantly smacked with debris as it moves, like bugs on a windshield. That debris creates the dark side, which heats up easily, so its ice sublimates and moves over to the white side and settles down there. So the dark side keeps getting darker, and the light side keeps getting lighter, resulting in the yin yang appearance here.

Iapetus’s dark side transitions to its light side, creating an effect that looks shiny.

Cassini captured the first close-up views of Iapetus in 2007. Here we see its ice-covered, bright side, and also a hint of the debris-strewn dark side.

A false-color image highlights Titan’s lakes of methane and ethane.

False colors indicate particle sizes inside the rings. Purple contains particles larger than two inches; green indicates particles smaller than two inches; and blue means particles are smaller still, at less than one third of an inch.

Another beautiful view of the geysers of Enceladus.

That’s no moon! Actually it is—it’s Saturn’s moon Mimas. But it looks like a Death Star thanks to Herschel Crater, which measures 81 miles across.

The tiny moon Pan casts a long, needlelike shadow across Saturn’s outer A ring.

Tethys soars past Saturn.

A false-color view highlights Rhea’s scratches and craters.

The speck in the center of this image is a moonlet measuring about 1,300 feet across. Cassini scientists discovered it thanks to its long shadow.

A wave moves across the rings, creating vertical undulations like corrugated cardboard.

Just a pretty picture of Saturn’s rings. The shadow of Mimas cuts across the lower left.

In this false-color image, Saturn’s auroras appear in green. As on other planets, including Earth, the auroras light up when charged particles from the sun crash into its magnetosphere.

Dione passes in front of Saturn and its rings, forming what looks like a :neutral_face:.

A giant hexagon, each side wider than Earth, sits at Saturn’s north pole. Exactly how it’s created remains a mystery.

Saturn’s northern hemisphere, as seen by Cassini from 1.9 million miles away.

Backlit by the sun, some of Saturn’s faintest rings become apparent.

A star shines through the B ring. Fluctuating light from the star helps scientists measure the density of ice and dust particles in the ring.

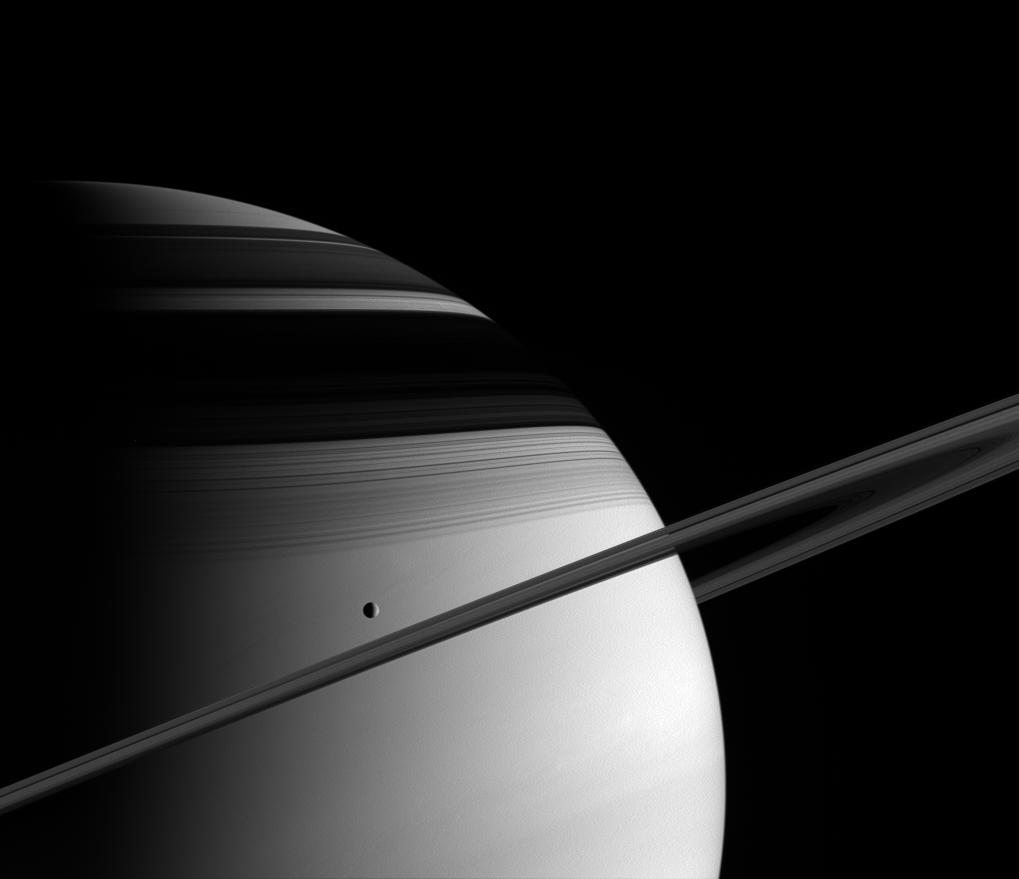

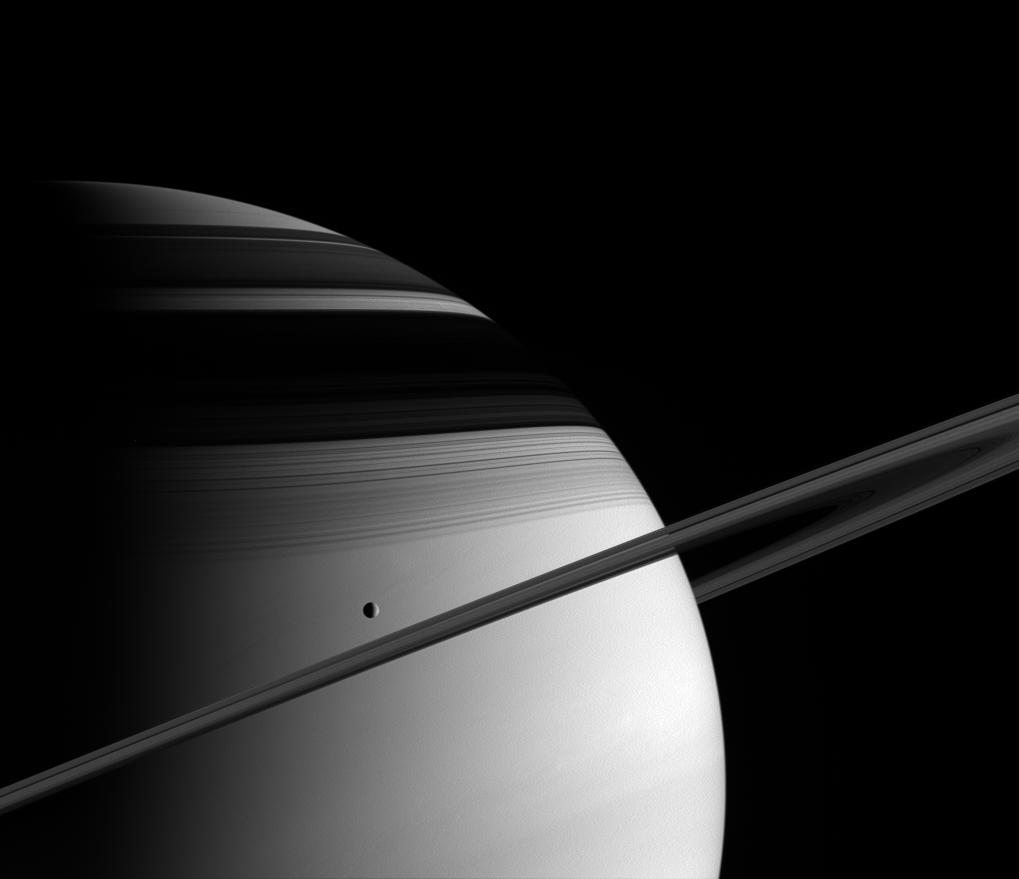

Ring shadows paint stripes across Saturn’s surface as Titan passes beneath the ring plane. The tiny white speck above the rings is the moon Prometheus, which is just 53 miles in diameter.

This is not a work of abstract art. It’s Titan and Dione, posing in front of Saturn and her rings.

Titan’s haze reflects light, creating this bright circle that looks like something out of The Ring (as if Saturn needed any more rings…). Enceladus passes in front of Titan, its southern geysers just barely visible.

The plumes of water shooting from the bottom of Enceladus may contain clues to the ocean within—and any tiny lifeforms that may live there.

Tethys (660 miles in diameter) looks tiny compared to the great gas giant. With a diameter of 72,367 miles, nine Earths could fit inside it in a straight line.

The outer layers of Titan’s thick atmosphere appear purple in this false-color image.

Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, passes in front of the ringed planet. The bluish tint in this natural color image indicates that it’s winter in the southern hemisphere.

A 1,250-mile-wide vortex spins at the center of Saturn’s giant hexagon. It’s about 50 times larger than the average hurricane eye on Earth.

A false-color view of the vortex at Saturn’s north pole, whose winds whip at a blistering 330 miles per hour.

Saturn has so many moons (62 at last count) that it’s not uncommon to see multiple moons in one shot. Here, Cassini captured three-in-one: Titan (the largest), Rhea (top left), and Mimas.