Seventy-four years ago, Russia accomplished what no country had before, or has since—it sent armed ground robots into battle. These remote-controlled Teletanks took the field during one of WWII’s earliest and most obscure clashes, as Soviet forces pushed into Eastern Finland for roughly three and a half months, from 1939 to 1940. The Finns, by all accounts, were vastly outnumbered and outgunned, with exponentially fewer aircraft and tanks. But the Winter War, as it was later called (it began in late November, and ended in mid-March), wasn’t a swift, one-sided victory. As the more experienced Finnish troops dug in their heels, Russian advancement was proving slow and costly. So the Red Army sent in the robots.

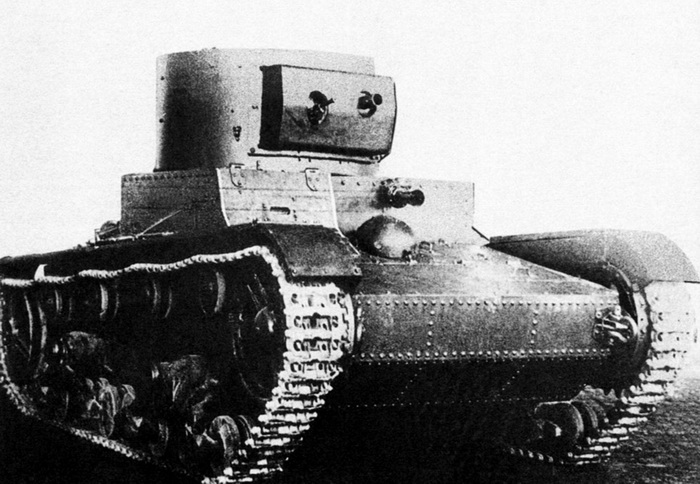

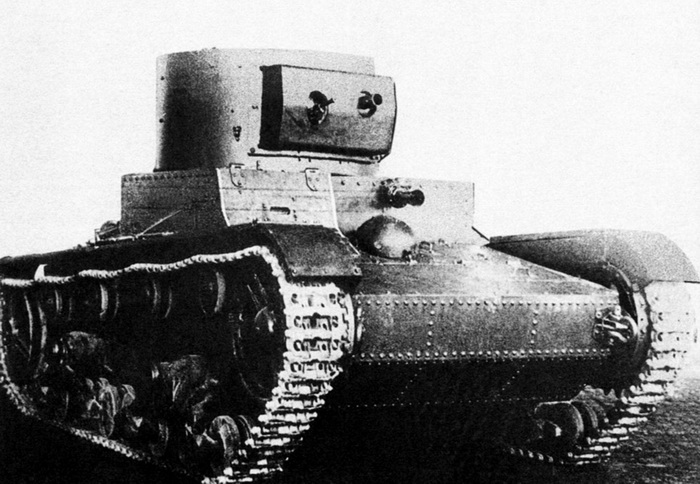

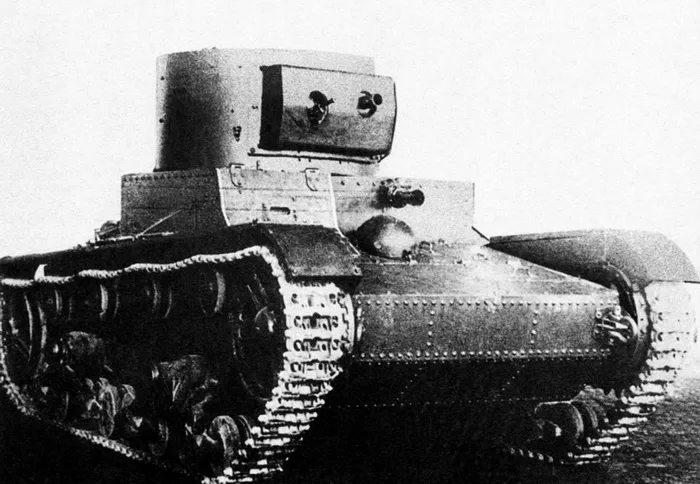

Specifically, the Soviets deployed two battalions of Teletanks, most of them existing T-26 light tanks stuffed with hydraulics and wired for radio control. Operators could pilot the unmanned vehicle from more than a kilometer away, punching at rows of dedicated buttons (no thumbsticks or D-pads to be found) to steer the tank or fire on targets with a machine gun or flame thrower. And the Teletank had the barest minimum of autonomous functionality: if it wandered out of radio range, the tank would come to a stop after a half-minute, and sit, engine idling, until contact was reestablished.

Notably missing, though, was any sort of remote sensing capability—the Teletank couldn’t relay sound or audio back to its human driver, most often located in a fully-crewed T-26 trailing behind the mechanized one. This was robotic teleoperation at its most crude, and made for halting, imprecise maneuvering across uneven terrain.

What good was the Teletank, then? Though records are sparse, the unmanned tanks appear to have been used in combat, including during the Battle of Summa, an extended, two-part engagement that eventually forced a Finnish retreat. The Teletank’s primary role was to throw fire without fear, offsetting its lack of accuracy with gouts of flame.

On March 13, 1940, Finland and the USSR signed a treaty in Moscow, ending the Winter War. It was the end of the Teletank, as well—in the wider, even more brutal conflict to come, the T-26 was obsolete in practically every way, lacking the armor and armament to stand up to German tanks, or even to antitank weapons fielded by the Finnish. With no additional units built after 1940, the T-26 was a dead design rolling, and the remote-controlled version was just as doomed.

For a few months, nearly three quarters of a century ago, Russia led the world in military robotics. It’s a position the country would never hold again, as both Soviet and post-breakup forces have all but abandoned the development of armed ground and aerial bots. Even as recently as 2008, during its conflict with Georgia—triggered, in part, by the downing of Georgian reconnaissance drones—Russian drones were all but absent, and its air strikes were entirely manned. While Russia hasn’t shied away from open warfare, it hasn’t made robots a battlefield priority.

Until recently, that is. A number of Russian-based aircraft makers have won contracts in the past few years to build combat drones, including a 5-ton model originally slated for testing this year, and a 20-ton model planned for 2018. Military officials now hope to have strike drone capability by 2020.

And while there’s no evidence that it will ever be deployed, Russia is, in fact, home to a gun-wielding ground drone. The MRK-27 BT, built by the Moscow Bauman Technical University and first unveiled in 2009, is a tracked weapon platform, armed with a machine gun and paired grenade launchers and flame throwers. Most likely, it will go the way of MAARS, SWORDS, MULE, and other imposing ground combat bots—which is to say, nowhere. So far, the Teletank is an anomaly among robotic weapons, a precursor with no real descendants. Or none, luckily, with any confirmed kills.