Lyme disease is in the news again, in part because you’re more likely to get the illness in the summertime. But what is it?

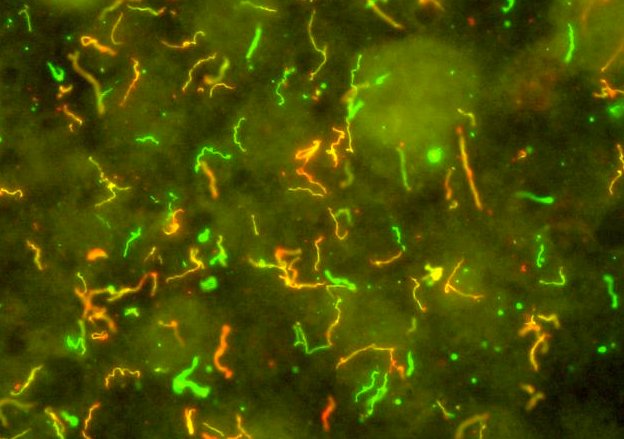

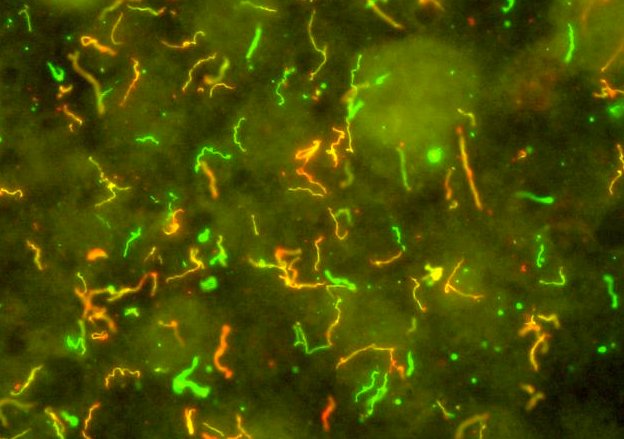

Lyme disease is caused by the bacterial spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi, which is related to the Treponema pallidum bacterium that causes syphilis. Most B. burgdorferi are spiral-shaped and can access almost an entire human body within days of infection, squiggling through their environment like calamitous corkscrews (see this great Scientific American post for more on how the bacteria move).

B. burgdorferi spread through tick bites—mainly black legged ticks, also called deer ticks. This species is small, particularly the nymphs, making it especially difficult to notice whether you’ve been bitten. The disease circulates in populations of deer and small wild rodents, which act as reservoirs, and ticks pick it up when they feed on infected animals. If an infected tick bites a person, the bacteria get a chance to jump into a new host.

Here is a photo of a female deer tick (and here is a site with more good photos):

Black legged ticks are mainly found along the east coast and down south, and a related species is located on the west coast. Still, it is more likely to get Lyme disease in the northeast, partly because of different feeding habits in different regions. In 2012, 95 percent of Lyme disease cases came from 13 states, mostly in New England and the Mid-Atlantic.

Ticks latch onto their host while they feed—see this great and horrifying video for specifics. A tick typically needs to be stuck to a host for 36-48 hours in order to pass B. burgdorferi , and since nymphs are harder to see, they are usually attached longer and are more likely to make you sick. Three days to a month after infection, some people get a rash in the shape of a bulls-eye, which can spread up to a foot in diameter. In its early stages, Lyme disease can also cause aches, chills, headache, fatigue, fever, and sore lymph nodes. Later symptoms may include Bell’s palsy, which is a loss of muscle tone in the face, as well as arthritis. Some people continue to have fatigue and other symptoms long after they’re treated—usually with antibiotics—and some claim these symptoms are evidence of a chronic Lyme illness, although the diagnosis is controversial.

The bad news is that both diagnosis and treatment for Lyme disease can be tricky. Not all patients get the obvious rash, and because the symptoms vary from one person to the next and match other illnesses, not everyone gets tested right away. There are diagnostic tests that are relatively accurate, although they’re imperfect.

But the good news is that it is relatively easy to prevent Lyme. You’re most likely to get infected if you spend time in grassy or wooded areas in parts of the world where the ticks are common, so if you aren’t hanging out in those places you’re probably okay. If you are out in the woods a lot in, say, New England, you can wear long-sleeved shirts, hats, and long pants tucked into your socks (stylish!) to keep your skin protected. Also use insect repellant, and stick with DEET or other tested products from the EPA’s recommended list. Be sure to shower when you get home and check your body for ticks—get a buddy to check your head and back.

And if you find a tick, remove it as soon as you can to lower the chances of disease transmission. But make sure you do it slowly and carefully, ideally with a good pair of tweezers, to make sure you don’t break the mouth off in your skin. Yuck.

***

Additional reading:

Lyme disease, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

How many people get Lyme disease? CDC

Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues, ed. Joseph P. Byrne, 2008.

The Rise of the Tick, by Carl Zimmer, Outside June 2013.

The Lyme Wars, by Michael Specter, The New Yorker July 2013.