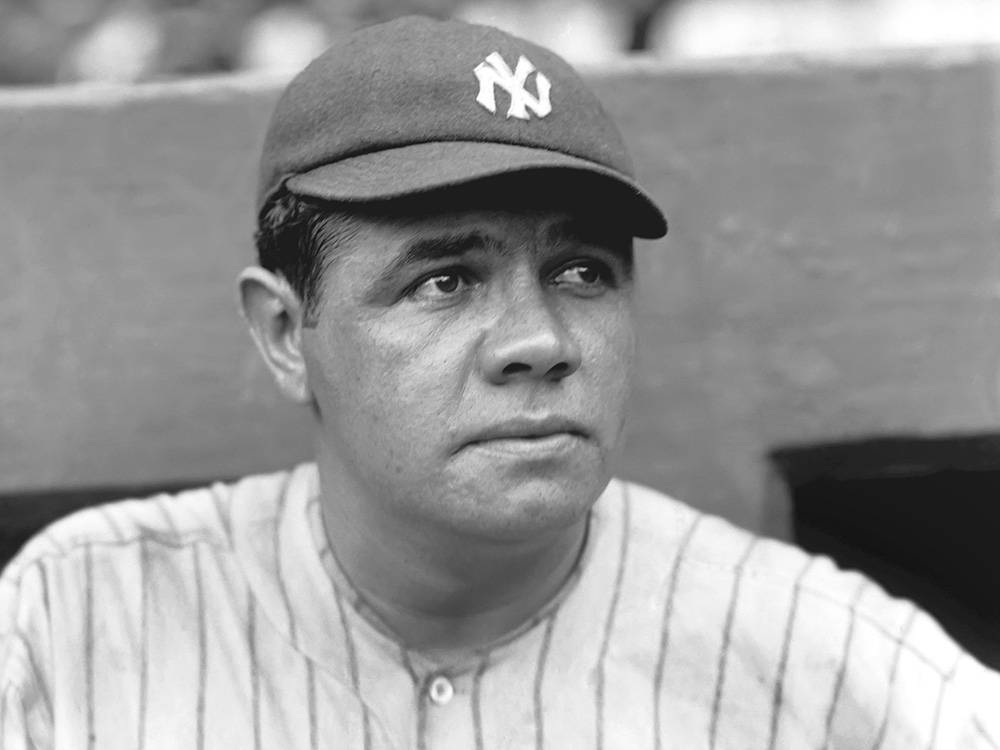

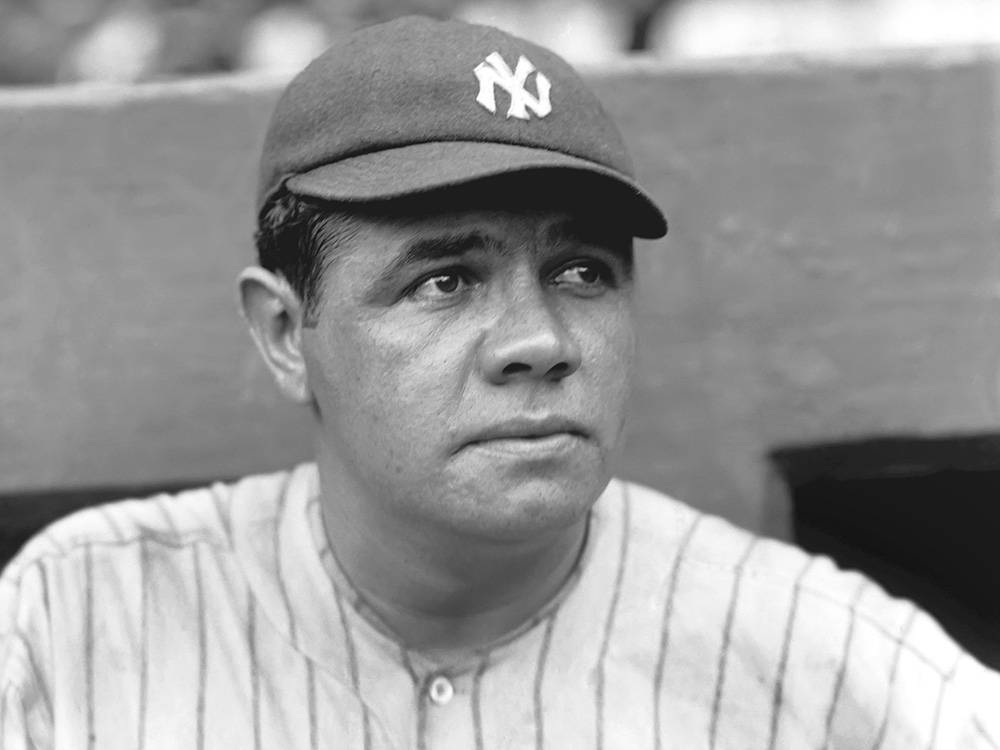

George Herman Ruth was sick. It had all started with a deep, searing pain behind his left eye. Now, he could hardly swallow. And the pain seemed to be seeping down his body, like an invisible weight tugging at his hips and legs. Soon, he’d have to use his bat as a cane. But he was no ordinary patient. He was the Babe, the greatest baseball player who had ever lived. And his medical team at what is now Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in Manhattan, just a short train ride south from Yankee Stadium, intended to treat him as such. While it seems possible that no one ever told Ruth himself, the baseball legend had terminal cancer. A tumor had grown from behind his nose to the base of his skull and was working its way into his neck. Treatment would be harrowing, but his doctors were determined the Sultan of Swat would get better. Though their effort to save him was ultimately unsuccessful, the record-setting Ruth became a cancer pioneer in the process.

At the time of Ruth’s birth on February 6, 1895, cancer, once a rarity, was suddenly everywhere. “He lived at a time when cancer rates were increasing markedly,” says Dr. Otis Brawley, Chief Medical Officer for the American Cancer Society. These days, Brawley says, we know what to attribute that to: smoking and air pollution. At the time, however, no one actually knew what caused cancer, let alone how to cure it.

Until the late 19th century, many scientists subscribed to the humoral theory of disease, which states that imbalances in blood, phlegm, and two types of bile caused all matter of illness. Others believed cancer, like tuberculosis, was contagious. And as late as the 1920s, some physicians subscribed to the notion that physical trauma caused tumors. This last theory persisted despite all evidence; scientists methodically injured lab animals aplenty and yet no new cancers grew.

Treatments were similarly brutish. For patients with breast cancer, the best that could be offered was total removal of the breasts. And that was better than most courses of treatment. While the mastectomies were painful and often proved unhelpful, at least some action could be taken. For people with cancer embedded deeper in their body, there was really only pain management and prayer.

But Ruth’s first year of life marked a turning point in the nascent field of cancer research. The death of Karl Thiersch, a German surgeon who correctly proposed that cancers grow through the spread of malignant cells, prompted other scientists to pick up his mantle and confirm the validity of his research. And German physics professor Wilhelm Roentgen’s discovery of the X-ray changed the world in more ways than one. It was clear that this wavelength would be crucial for medical imaging (for the first time, you could see inside people without wielding a knife), but it would be only a few months before scientists realized X-rays had therapeutic value, too.

In 1896, one enterprising French physician initiated the first attempt to use X-ray as therapy. He trained an X-ray on a patient’s stomach tumor for 15 to 30 minutes twice a day for more than a month. According to his report, the mass shrank and the patient reported relief. Though the subject later died of their disease, the short-term successes encouraged doctors all over the world to try this therapy for themselves. The experimental treatment worked by training a beam of radiation on a patient and damaging the DNA of any cell caught in the crossfire, preventing them from replicating further.

Over the next 10 years, X-ray therapy would be tested as a potential cure for a plethora of ailments, from Hodgkin’s lymphoma to non-cancerous skin issues like acne. Unfortunately, these early beams were indiscriminate; they often destroyed as many good cells as cancerous ones. As late as the 1950s, radiation machines still seemed to do as much harm as good. “They burned a lot of patients with the radiation,” Brawley says. What’s more, “the radiation was not really able to penetrate into, say, a head-neck tumor.”

Another avenue of radiation therapy was also developing around this time. In 1898, Marie Curie discovered radium, the radioactive substance that causes her laboratory notebooks to glow to this day. By the 1910s, as Ruth entered the major league, medical usage of radioactive substances surged. Researchers had started to differentiate the numerous ways in which radium could be injected into a patient’s body. Unlike X-ray therapy, which had to be beamed in from the outside, researchers could experiment with radium inhalation, therapeutic baths in the substance, radium salts inserted directly into the diseased area, and other methods of attack.

Finding a way to deploy the cancer-fighting agent responsibly was still decades away. Like Curie, who died of aplastic anemia as a result of her radium and polonium exposure, many early researchers—and the patients they worked on—were sickened by their would-be cure. “Radiation was a very primitive type of thing in the 20s and 30s,” Brawley says. “They literally used the same machines they used to do chest X-rays, they just turned them on longer.”

For much of the 20th century, cancer was still considered generally incurable; most cancer patients, a lost cause. “Even in the early 1970s, people couldn’t say ‘cancer,'” Brawley says. “It was considered a bad word.” Patients were typically not told the truth about their diagnoses. Instead, they were provided excuses and euphemisms. Though it may seem strange or even unethical today, families and physicians feared that if patients knew the truth, they’d lose hope.

As World War II came to a close, a new day was dawning in medicine. And good thing, too, because Babe Ruth had just lost his voice.

A hoarse voice can mean many things, most of which aren’t life-threatening. As a lifelong smoker and the literal posterboy for White Owl cigars and Raleigh cigarettes, it was plausible that Babe Ruth just couldn’t smoke the way he used to, and that the problem would go away on its own if he cut back.

But between September and November of 1946, things only got worse. Ruth’s runaway voice was accompanied by severe eye pain and weakness in his record-breaking shoulders. At a doctor’s appointment in Manhattan’s now-defunct French Hospital, doctors found exactly what they feared: A tumor protruding from the base of Ruth’s skull.

Dr. Nadim Bikhazi, an ear, nose, and throat doctor, is the author of a headline-making 1999 article for the journal Laryngoscope titled “‘Babe’ Ruth’s illness and its impact on medical history.” In his paper, Bikhazi used the remaining scraps of Ruth’s original medical reports to piece together the progression of the legend’s disease. Though it appears Ruth was never told he had cancer—when Ruth arrived at Memorial Sloan-Kettering for treatment, he reportedly said, “Doc, this is Memorial. Memorial is a cancer hospital. Why are you bringing me here?”—he was swiftly subjected to the painful cancer therapies of the day.

He received X-ray therapy to his head, failed surgery to remove the mass, and injections of female hormones, as some incorrectly theorized his cancer may have been caused by chemical imbalances of some kind. (Hormones do a play a role in some cancers, including those of the breast, ovary, and uterus, but were likely irrelevant to Ruth’s head-neck disease.) “In total,” Bikhazi wrote, “he had spent [three] months in the hospital, had lost approximately 80 [pounds], and remained in great pain.” Over the course of the next two years, Ruth would also receive other largely unhelpful interventions including rest, relaxation, and radiated gold seeds, which were implanted into his neck. “They were clearly reaching for a lot of things,” Bikhazi says.

In the summer of 1947, however, Ruth was offered a trial therapy of an entirely new class of cancer treatment. He was, Bikhazi says, “in the right city at the right time.”

“Chemotherapy came to us because of an accident in World War II,” says Brawley of the American Cancer Society. In 1944, German bombers attacked the Allied forces at a port in Bari, where Italy’s boot meets its heel. The air raid itself killed troops and civilians and damaged military supplies. But it was what the Americans were hiding in one of the wrecked cargo ships that made the event historic: The U.S. SS John Harvey contained more than 120,000 pounds of mustard gas. As the ship sunk into the sea, it released its secret stash, poisoning some 628 people. Within the month, at least 83 were dead.

It was a tragic event—and a shameful one, as the Geneva Convention had outlawed chemical weapons almost 20 years before. Given its inherent illegality, the United States and British governments worked quickly to cover the crisis up, suppressing Bari’s secrets for decades. But the data could not be denied. Based on tissue samples stealthily collected from the bodies of autopsied victims, scientists saw for the first time the therapeutic potential of this chemical concoction.

“One of the effects of people exposed to mustard gas,” Brawley says, “[is that] their white blood cell counts come down.” Researchers hypothesized that mustard gas might be used to treat cancers like leukemia, which results in abnormally high concentrations of white blood cells. Doctors also noted that in many victims, the somatic cells, which normally branch off around the clock to restore aging or dying cells, ceased to divide. Given that cancer is the result of cell division gone wild, this result indicated another potentially positive effect of the chemicals.

After the war, scientists sought to put this knowledge to work in the clinic. Confident now that chemicals could combat cancer, Boston pediatrician Sidney Farber, who would come to be known as the father of modern chemotherapy, began conducting his own experiments on children with leukemia. He saw that folic acid encouraged the proliferation of disease in his patients. From this observation, Farber decided to administer doses of the opposite chemical, folate antagonists, to children under his care. To his delight, every single patient in his small study went into remission. Though none were permanently cured, the principle was established: Antifolates could be an important avenue for cancer-fighting drug development.

“They actually had some therapeutic responses,” Brawley says of Farber’s experiments. “No cures, but therapeutic responses. That led other folks to use some of the folate antagonists; in fact, one of the early folate antagonists was the one that was given to Ruth.”

The drug that Ruth took was called teropterin. Richard Lewisohn, a researcher at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City, extracted the antifolates from brewer’s yeast. The compound seemed to work in a few mice, but it had never been tried in humans. Against Lewisohn’s will, the nascent drug was nonetheless made available for Ruth’s use. “It went from mice to Babe Ruth,” Bikhazi says with a sense of amazement, even after all these years. “There was no intermediary.”

Miraculously, the drug worked. At least for a short time. Ruth started daily injections on June 29, 1947. In short order, Bikhazi reports, he gained back some of the weight he’d lost, reported less pain, and was finally able to swallow solid food. He continued chemotherapy for about six weeks and various radiation treatments for another year, as doctors cast about in search of a permanent cure. They never found one, and Ruth ultimately died of cancer on August 16, 1948, at the age of 53. But in the process of that trial and error treatment, Bikhazi reports, Ruth became perhaps the first patient to receive sequential radiation and chemotherapy. Now called “chemo-beamo,” this two-pronged approach is standard treatment for many cancers today.

Bikhazi says the coordinated attack extended Ruth’s lifespan significantly beyond the prognosis of the day. Perhaps most importantly for the Americans who so admired Ruth, the drug allowed him to live long enough to say goodbye to Yankee Stadium on June 13, 1948, just two months before his death. On that last visit to “the House that Ruth Built,” he retired his No. 3 jersey and permanently sealed his No. 3 locker. Later, while leaning on his bat for support, Ruth received a standing ovation from the crowd.

For half a century, doctors believed that Ruth had cancer in his larynx, which grows from the voice box in the throat. The hoarse speech, as well as Ruth’s prolific consumption of cigarettes and alcohol, supported this theory. But by evaluating Ruth’s private autopsy reports, Bikhazi showed that Ruth actually had nasopharyngeal cancer, a rare illness that starts behind the nose. More than 70 years after his death, the distinction might seem minor, but the takeaway is staggering: Ruth, through sheer dumb luck, got almost exactly the right treatment. Laryngeal cancer typically requires radiation and surgery (including total removal of the voicebox), but nasopharyngeal cancer is still tackled with chemo-beamo today. “If Ruth had presented today with advanced-stage nasopharyngeal cancer as he had in 1946,” Bikhazi wrote, “he would have had a favorable chance of long-term survival.”

Bikhazi, who put the pieces of Babe’s illness together in spite of damaged and even intentionally destroyed records, sees the story as an inherently uplifting one. At the very least, it’s a reminder of how far cancer treatments have come. But that doesn’t mean the tale is entirely rosy. “One of the problems in medicine is that there has always been this concept that people who are famous get treated special,” Brawley says. “It’s not a surprise to my mind that they threw thing after thing at him because he was Babe Ruth.” While Ruth got the time he needed to say goodbye, no one else did, as experimental drugs like teropterin weren’t made available to the masses and chemotherapy wasn’t widely available until the 1950s.

More unnerving, perhaps, is the evidence that suggests Ruth was largely in the dark about his own illness. While it cannot be confirmed—his family says he didn’t know, but contemporaneous reports of his death clearly describe the cancer that killed him—Ruth’s potential ignorance of his own disease calls into question the ethics of his doctor’s decisions. Medical principles and the rules around clinical trials have evolved dramatically since Ruth’s time, and today no one would be allowed to undergo experimental treatment without being fully briefed on the risks they were taking on.

Still, Bikhazi says, Ruth’s contributions to medical history are bigger than any criticism. Thanks to patients like Ruth and scientists like Farber and Lewisohn, new chemotherapy drugs are more potent and more targeted than ever. The same is true of radiation. Instead of exposing an entire region of a patient’s body to a giant X-ray machine, hundreds of razor-thin beams can be trained onto a tumor to bypass most of the healthy issue as they attack the cancerous cells. “A shotgun approach is the old way of doing it,” Brawley says of Ruth’s era. “A sniper is the new way.”

Perhaps most significantly, the publicity Ruth’s disease would eventually receive helped to eat away at the stigma cancer patients felt for centuries. Efforts in subsequent decades by other prominent cancer survivors, like First Lady Betty Ford, ushered in a world in which patients are informed and consulted about their disease and its treatment and, crucially, treated with dignity throughout the process.

After his death, Babe Ruth lay in state at Yankee Stadium, where fans lined up to pay their respects. Photographers on the scene captured tender moments as boys, young and old, cried over the Babe. The treatments at the time weren’t capable of curing their hero, but the medical innovations Ruth shepherded along have gone on to cure countless others. One likes to assume Ruth would be selflessly proud of his contributions. After all, his most famous quote is equally applicable to baseball as it is to the fight against cancer: “Never let the fear of striking out get in your way.”