Nine years ago, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) made history when its Hayabusa probe successfully brought samples of the asteroid Itokawa back to Earth. It was the first time we had ever gone to an asteroid, collects samples off the surface, and brought them back in pristine condition for study.

Now, according to findings recently published in the journal Science Advances, those samples have made history once again: they contain water.

“No one really expected to find even traces of water in the Itokawa grains,” says Maitrayee Bose, a cosmochemist at Arizona State University. It’s well-known that Itokawa (or rather, the parent body it descended from) had been torched to up to 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit, and perhaps higher when impacted by other rocks strewing around through space. There wasn’t much hope any water would be still preserved after such extreme conditions. “Before we embarked on this work, our back of the envelope calculations showed that it is indeed possible for the Itokawa grains to retain the original water in the right proportion from when the asteroid formed,” Bose says. “This is the first time someone has ever measured water in this asteroid.”

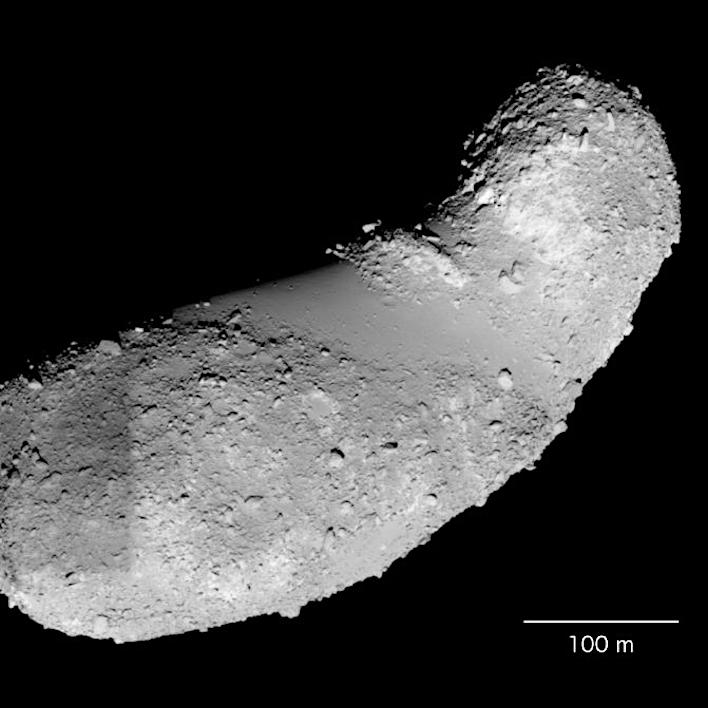

Itokawa is a 1,800-foot-long, 1,000-foot-wide rock orbiting the sun every 18 months, about 1.3 times farther from the sun than Earth is. It’s the remnant of a larger asteroid that was probably about 12 miles wide before a series of catastrophic impacts shattered it into several large fragments—two of which eventually merged into its present-day shape about 8 million years ago. It’s one of the most common types of asteroids in the solar system, so finding traces of water in spite of all its harsh experiences in the vacuum of space has some very tantalizing implications.

Bose’s research is specifically aimed at studying the internal chemistry of small bodies in the solar system to understand how they acquire and sustain the building blocks for life. He’s especially interested in understanding whether asteroids and other small rocks are able to deliver water and organics to different worlds that would otherwise remain barren. “We find ourselves on this ‘pale blue dot,’ a planet full of water, rich in organics and supportive of life,” says Bose. “We know of no other such planet. My aim is to find out how.”

Bose wrote a proposal that successfully convinced the JAXA to make five of the 1,500 Itokawa sample grains—each about half as thick as a strand of hair—available for study. The team found that two of the five grains possess the mineral pyroxene. On Earth, pyroxenes contain water as a part of their crystalline structures, and so Bose suspected the asteroidal pyroxenes should also contain traces of water as well.

To find the water, Bose turned to his university’s NanoSIMS instrument: an ion mass spectrometer with the rare ability to measure very tiny mineral grains with extraordinary sensitivity. The pyroxenes turned out to be surprisingly rich in water—about 0.1 percent. This sounds low, and Bose emphasizes Itokawa is “bone dry” compared to what humans are used to here on Earth. But it’s still much wetter than expected, and you’ve got to remember that’s a pretty significant amount of water for minerals you can’t even see with the naked eye. The results are enough to make the researchers speculate that dry asteroids like Itokawa could harbor much more water than previously thought.

The team’s findings also suggest that, if the chemistry is ideal, impacts from these asteroids might be responsible for as much as half of the water that makes up Earth’s oceans. This is critical, since many theorize much of Earth’s water come to the planet through repeated asteroid bombardments during more chaotic days within the solar system.

“The source of water on Earth and other planets like Mars is hotly debated in the planetary science community,” says Bose. “The most popular scenario is that water on Earth was delivered by water-rich asteroids from the outer solar system during different periods of planetary formation. Small asteroid bodies in the inner solar system could be a source of water for Earth and other planets. You can think of these small bodies… as being the fundamental building blocks of planets, bringing water and other materials, like organics, to the planets.”

The success of this latest study primes Bose and his lab to follow up with some more heavy-hitting discoveries. Analyses of another mineral called olivine suggest there are other approaches for finding even more hidden deposits of water entrenched within asteroids like Itokawa. He and his team are also interested in studying samples that will be acquired from asteroid Bennu (through NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission, which aims to return in 2023) and asteroid Ryugu (through JAXA’s Hayabusa-2 mission, which aims to return in 2020). These latest findings are likely only the prelude to a slew of new research involving asteroids and water.