It doesn’t look much like a heart, but it works—a little bit—like one. Researchers have created a microchip heart that has a rare genetic disease. Using the chip, the researchers were able to learn some basics about the disease, called Barth syndrome, that scientists didn’t know before.

These results are a step forward for Barth syndrome research, of course. The syndrome, usually found in boys, causes enlarged, weakened hearts; muscle weakness; and immune system trouble. It has no cure. The research also happens to show off a fascinating application for organs-on-a-chip, a technology that engineers developed in recent years to study human biology in an entirely new way.

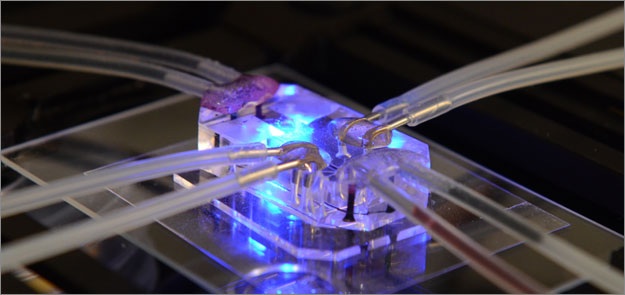

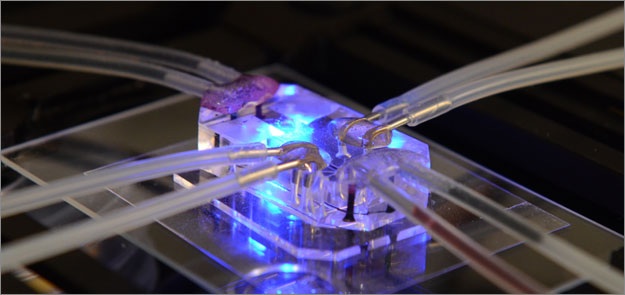

To make organs-on-a-chip, engineers gather cells from people and spread them inside little plastic squares similar in size to computer microchips. The organs-on-a-chip often have minuscule sensors and tubing so that scientists are able to pump chemicals into them and measure different results. For example, scientists could pump medicine into an organ-on-a-chip and see how cells react. The chips are supposed to be an alternative to doing tests in lab animals. They have their advantages and disadvantages, compared to lab animals. One thing’s for sure: They are much cooler than lab rats.

When the heart cells beat strongly enough, the whole chip bent.

To make Barth-syndrome chips, researchers from the U.S. and Europe took skin biopsies from two people with Barth syndrome. The researchers transformed the skin cells into stem cells, and from there into heart cells that could beat on their own. Even after all those transformations, the cells still had the same genes they originally did—including the one faulty gene that causes Barth syndrome. That gene is important to making mitochondria, specialized structures that appear in every cell.

The researchers put the Barth-syndrome heart cells into their chips, which were made of soft plastic. When the heart tissue beat strongly enough, the whole chip bent. The researchers measured the bend of the chip to calculate how strongly the heart cells worked.

From the chip experiments and others, the Barth syndrome researchers learned that the Barth-syndrome gene, which appears on the X chromosome, caused heart cells to beat more weakly. You can see typical heart cells on a chip, compared to the barely-beating the Barth-syndrome heart cells, below. Both sets of cells were made from skin cells, turned into stem cells, turned into heart cells:

Megan McCain and Kevin Kit Parker/Wyss Institute

The Barth-syndrome gene also made the heart cells produce an excess of chemicals called reactive oxygen species. On the other hand, clearing out the excess reactive oxygen species helped the heart cells beat more normally. “Now, whether that can be achieved in an animal model or a patient is a different story, but if that could be done, it would suggest a new therapeutic angle,” William Pu, the research’s lead scientist and a cardiologist at Boston Children’s Hospital, said in a statement.

Pu and his colleagues published their work on Monday, in the journal Nature Medicine.