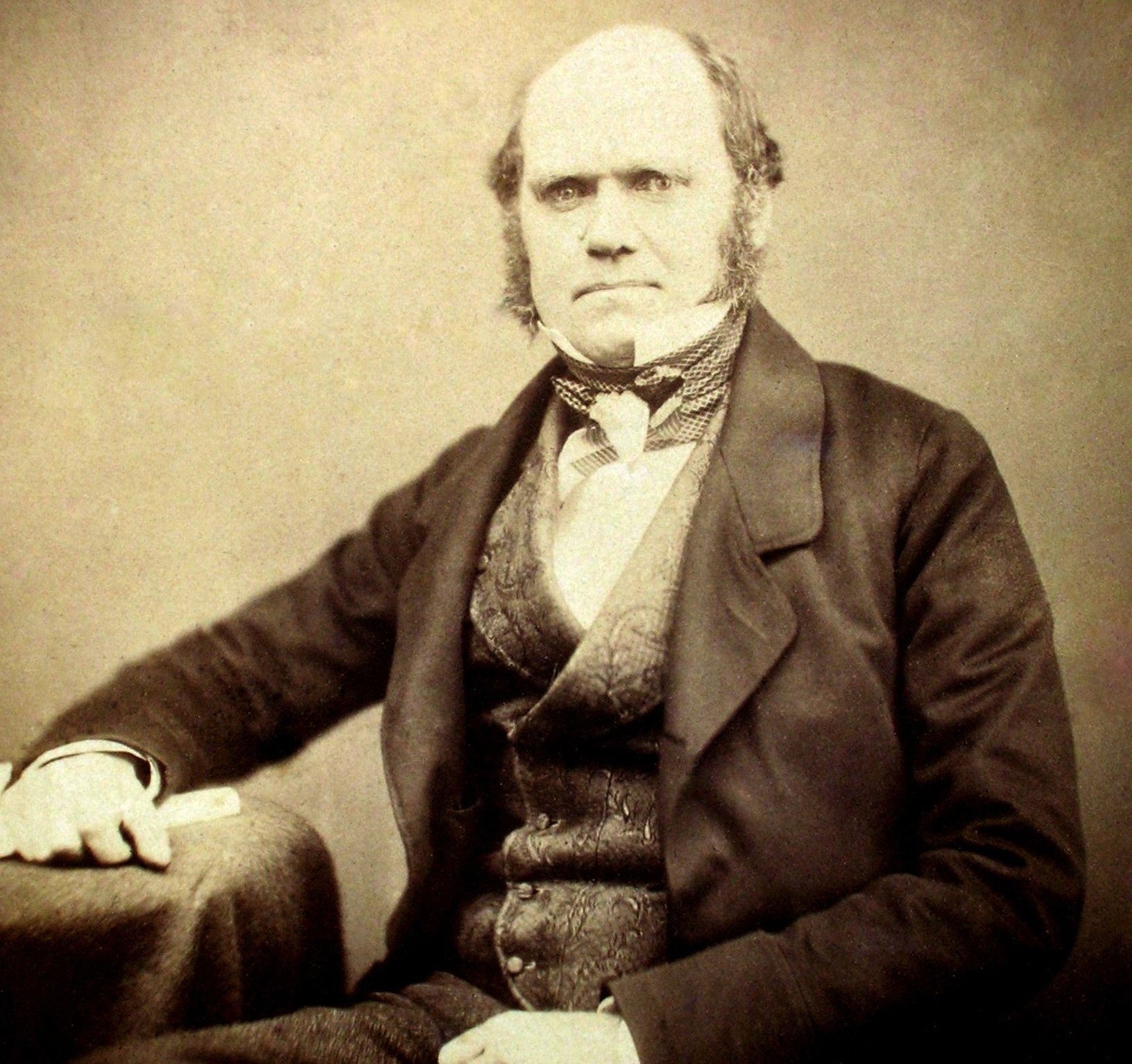

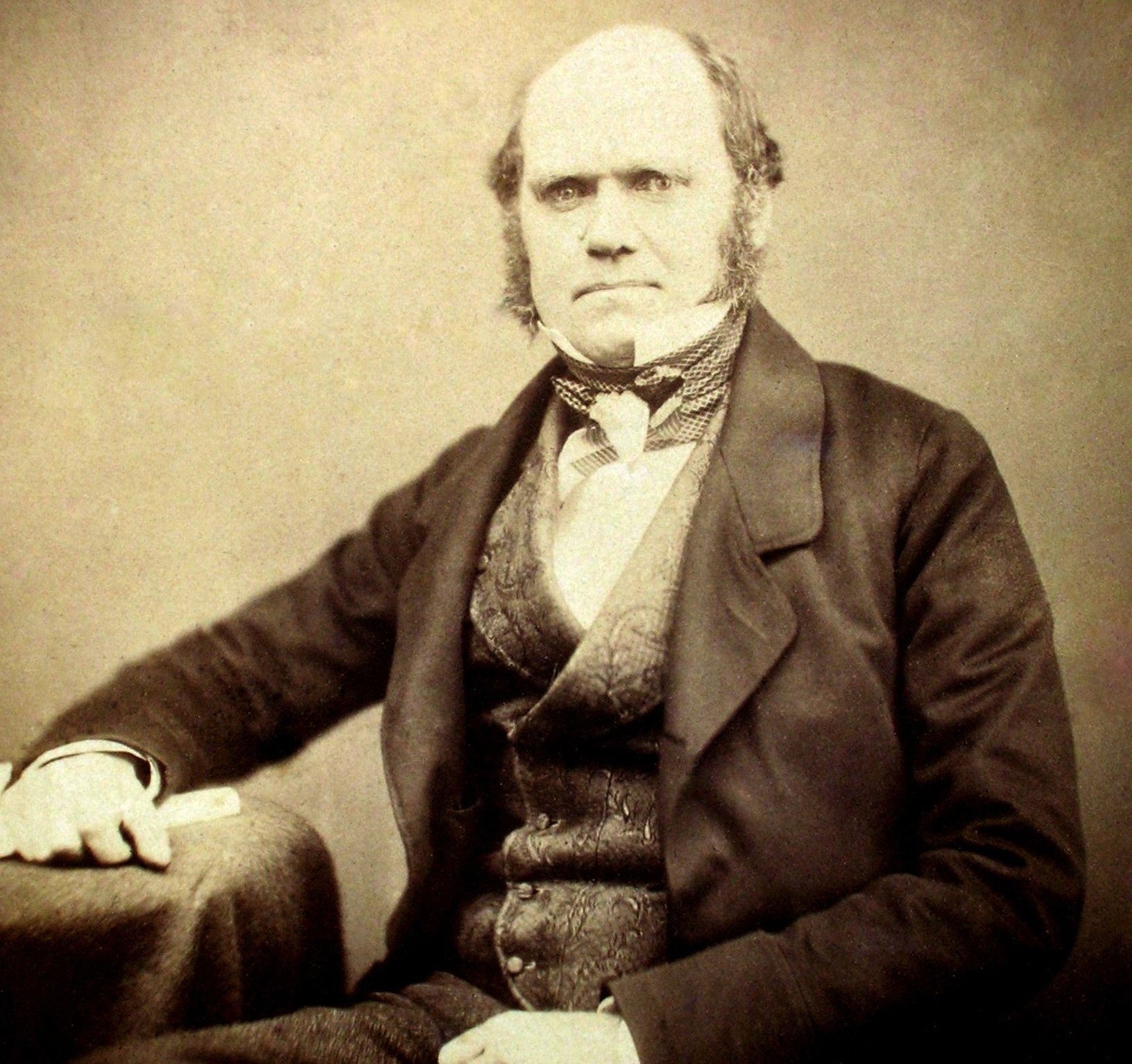

These letters originally appeared in the March 1903 issue of Popular Science. The “Hitherto Unpublished Letters of Charles Darwin” were compiled and edited by Darwin’s son, Francis Darwin, and the British botanist Albert Charles Seward. Today would have been Darwin’s 205th birthday.

To A. R. WALLACE.

DOWN, April 6th, 1859.

I this morning received your pleasant and friendly note of November 30th. The first part of my MS.* is in Murray’s hands to see if he likes to publish it. There is no preface, but a short introduction, which must be read by every one who reads my book. The second paragraph in the introduction I have had copied verbatim from my foul copy, and you will, I hope, think that I have fairly noticed your paper in the Linn. Journal. You must remember that I am now publishing only an abstract, and I give no references. I shall, of course, allude to your paper on distribution; and I have added that I know from correspondence that your explanation of your law is the same as that which I offer.

You are right, that I came to the conclusion that selection was the principle of change from the study of domesticated productions; and then, reading Malthus, I saw at once how to apply this principle. Geographical distribution and geological relations of extinct to recent inhabitants of South America first led me to the subject: especially the case of the Galapagos Islands.

I hope to go to press in the early part of next month. It will be a small volume of about five hundred pages or so. I will of course send you a copy. I forget whether I told you that Hooker, who is our best British botanist and perhaps the best in the world, is a full convert, and is now going immediately to publish his confession of faith; and I expect daily to see proof-sheets. Huxley is changed, and believes in mutation of species: whether a convert to us, I do not quite know. We shall live to see all the younger men converts. My neighbour and an excellent naturalist, J. Lubbock, is an enthusiastic convert. I see that you are doing great work in the Archipelago; and most heartily do I sympathise with you. For God’s sake take care of your health. There have been few such noble labourers in the cause of Natural Science as you are.

P. S. You cannot tell how I admire your spirit, in the manner in which you have taken all that was done about publishing all our papers. I had actually written a letter to you, stating that I would not publish anything before you had published. I had not sent that letter to the post when I received one from Lyell and Hooker, urging me to send some MS. to them, and allow them to act as they thought fair and honestly to both of us; and I did so.

*Darwin is referring to “On the Origin of Species.”

To J. D. HOOKER.

DOWN, Nov. 20th [1862].

Your last letter has interested me to an extraordinary degree, and your truly parsonic advice, ‘some other wise and discreet person,’ etc., etc., amused us not a little. I will put a concrete case to show what I think A. Gray believes about crossing and what I believe. If 1,000 pigeons were bred together in a cage for 10,000 years their number not being allowed to increase by chance killing, then from mutual intercrossing no varieties would arise; but, if each pigeon were a self-fertilising hermaphrodite, a multitude of varieties would arise. This, I believe, is the common effect of crossing, viz., the obliteration of incipient varieties. I do not deny that when two marked varieties have been produced, their crossing will produce a third or more intermediate varieties. Possibly, or probably, with domestic varieties, with a strong tendency to vary, the act of crossing tends to give rise to new characters; and thus a third or more races, not strictly intermediate, may be produced. But there is heavy evidence against new characters arising from crossing wild forms; only intermediate races are then produced. Now, do you agree thus far? if not, it is no use arguing; we must come to swearing, and I am convinced I can swear harder than you, .-. I am right. Q.E.D.

If the number of 1,000 pigeons were prevented increasing not by chance killing, but by, say, all the shorter-beaked birds being killed, then the whole body would come to have longer beaks. Do you agree?

Thirdly, if 1,000 pigeons were kept in a hot country, and another 1,000 in a cold country, and fed on different food, and confined in different-size aviary, and kept constant in number by chance killing, then I should expect as rather probable that after 10,000 years the two bodies would differ slightly in size, colour, and perhaps other trifling characters; this I should call the direct action of physical conditions. By this action I wish to imply that the innate vital forces are somehow led to act rather differently in the two cases, just as heat will allow or cause two elements to combine, which otherwise would not have combined. I should be especially obliged if you would tell me what you think on this head.

Now, do you agree thus far? if not, it is no use arguing; we must come to swearing, and I am convinced I can swear harder than you.

But the part of your letter which fairly pitched me head over heels with astonishment, is that where you state that every single difference which we see might have occurred without any selection. I do and have always fully agreed; but you have got right round the subject, and viewed it from an entirely opposite and new side, and when you took me there I was astounded. When I say I agree, I must make the proviso, that under your view, as now, each form long remains adapted to certain fixed conditions, and that the conditions of life are in the long run changeable; and second, which is more important, that each individual form is a self-fertilising hermaphrodite, so that each hair-breadth variation is not lost by intercrossing. Your manner of putting the case would be even more striking than it is if the mind could grapple with such numbers—it is grappling with eternity—think of each of a thousand seeds bringing forth its plant, and then each a thousand. A globe stretching to the furthest fixed star would very soon be covered. I cannot even grapple with the idea, even with races of dogs, cattle, pigeons, or fowls; and here all admit and see the accurate strictness of your illustration.

Such men as you and Lyell thinking that I make too much of a Deus of Natural Selection is a conclusive argument against me. Yet I hardly know how I could have put in, in all parts of my book, stronger sentences. The title, as you once pointed out, might have been better. No one ever objects to agriculturists using the strongest language about their selection, yet every breeder knows that he does not produce the modification which he selects. My enormous difficulty for years was to understand adaptation, and this made me, I cannot but think, rightly, insist so much on Natural Selection. God forgive me for writing at such length; but you cannot tell how much your letter has interested me, and how important it is for me with my present book in hand to try and get clear ideas. Do think a bit about what is meant by direct action of physical conditions. I do not mean whether they act; my facts will throw some light on this. I am collecting all cases of bud-variations, in contradistinction to seed-variations (do you like this term, for what some gardeners call ‘sports’?); these eliminate all effects of crossing. Pray remember how much I value your opinion as the clearest and most original I ever get.

I see plainly that Welwitschia will be a case of Barnacles.

I have another plant to beg, but I write on separate paper as more convenient for you to keep. I meant to have said before, as an excuse for asking for so much from Kew, that I have now lost two seasons, by accursed nurserymen not having right plants, and sending me the wrong instead of saying that they did not possess.

To ASA GRAY.

DOWN, Nov. 29th [1859].

This shall be such an extraordinary note as you have never received from me, for it shall not contain one single question or request. I thank you for your impression on my views. Every criticism from a good man is of value to me. What you hint at generally is very, very true: that my work will be grievously hypothetical, and large parts by no means worthy of being called induction, my commonest error being probably induction from too few facts. I had not thought of your objection of my using the term ‘natural selection’ as an agent. I use it much as a geologist does the word denudation—for an agent, expressing the result of several combined actions.

I will take care to explain, not merely by inference, what I mean by the term; for I must use it, otherwise I should incessantly have to expand it into some such (here miserably expressed) formula as the following: “The tendency to the preservation (owing to the severe struggle for life to which all organic beings at some time or generation are exposed) of any, the slightest, variation in any part, which is of the slightest use or favourable to the life of the individual which has thus varied; together with the tendency to its inheritance.” Any variation, which was of no use whatever to the individual, would not be preserved by this process of ‘natural selection.’ But I will not weary you by going on, as I do not suppose I could make my meaning clearer without large expansion. I will only add one other sentence: several varieties of sheep have been turned out together on the Cumberland mountains, and one particular breed is found to succeed so much better than all the others that it fairly starves the others to death. I should here say that natural selection picks out this breed, and would tend to improve it, or aboriginally to have formed it. . . .

You speak of species not having any material base to rest on, but is this any greater hardship than deciding what deserves to be called a variety, and be designated by a Greek letter? When I was at systematic work I know I longed to have no other difficulty (great enough) than deciding whether the form was distinct enough to deserve a name, and not to be haunted with undefined and unanswerable questions whether it was a true species. What a jump it is from a well- marked variety, produced by natural cause, to a species produced by the separate act of the hand of God! But I am running on foolishly. By the way, I met the other day Phillips, the palaeontologist, and he asked me, ‘How do you define a species?’ I answered, ‘I can not.’ Whereupon he said, ‘At last I have found out the only true definition—any form which has ever had a specific name! . . .’

To ASA GRAY.

DOWN, July 23rd [1862].

I received several days ago two large packets, but have as yet read only your letter; for we have been in fearful distress, and I could attend to nothing. Our poor boy had the rare case of second rash and sore throat . . .; and, as if this was not enough, a most serious attack of erysipelas, with typhoid symptoms. I despaired of his life; but this evening he has eaten one mouthful, and I think has passed the crisis. He has lived on port wine every three-quarters of an hour, day and night. This evening, to our astonishment, he asked whether his stamps were safe, and I told him of one sent by you, and that he should see it to-morrow. He answered, ‘I should awfully like to see it now’; so with difficulty he opened his eyelids and glanced at it, and, with a sigh of satisfaction, said, ‘All right.’ Children are one’s greatest happiness, but often and often a still greater misery. A man of science ought to have none—perhaps not a wife; for then there would be nothing in this wide world worth caring for, and a man might (whether he could is another question) work away like a Trojan. I hope in a few days to get my brains in order, and then I will pick out all your orchid letters, and return them in hopes of your making use of them. . . .

Of all the carpenters for knocking the right nail on the head, you are the very best; no one else has perceived that my chief interest in my orchid book has been that it was a ‘flank movement’ on the enemy. I live in such solitude that I hear nothing, and have no idea to what you allude about Bentham and the orchids and species. But I must enquire.

By the way, one of my chief enemies (the sole one who has annoyed me), namely Owen, I hear has been lecturing on birds; and admits that all have descended from one, and advances as his own idea that the oceanic wingless birds have lost their wings by gradual disuse. He never alludes to me, or only with bitter sneers, and coupled with Buffon and the Vestiges.

Well, it has been an amusement to me this first evening, scribbling as egotistically as usual about myself and my doings; so you must forgive me, as I know well your kind heart will do. I have managed to skim the newspaper, but had not heart to read all the bloody details. Good God! what will the end be? Perhaps we are too despondent here; but I must think you are too hopeful on your side of the water. I never believed the ‘canards’ of the army of the Potomac having capitulated. My good dear wife and self are come to wish for peace at any price. Good night, my good friend. I will scribble on no more.

One more word. I should like to hear what you think about what I say in the last chapter of the orchid book on the meaning and cause of the endless diversity of means for the same general purpose. It bears on design, that endless question. Good night, good night!

Read the rest of the letters in the March 1903 issue of _Popular Science magazine._