More than 98 percent of all scientific articles published today are in English, but that hasn’t always been the case. “There used to be one language of science in Europe, and it was Latin,” says Michael Gordin, a historian of science at Princeton University who is writing a book about the selection of scientific languages. But researchers began to move away from Latin in the 17th century. Galileo, Newton, and others started writing papers in their native tongues in part to make their work more accessible and in part as a reaction to the Protestant Reformation and the declining influence of the Catholic Church.

Once Latin was unseated as its lingua franca, scientific discourse splintered into local languages. Researchers worried that the loss of a common tongue would slow scientific progress, so by the middle of the 19th century, they had settled on three primary languages.“If you were a professional scientist,” Gordin says, “you were expected to read French, English, and German.”

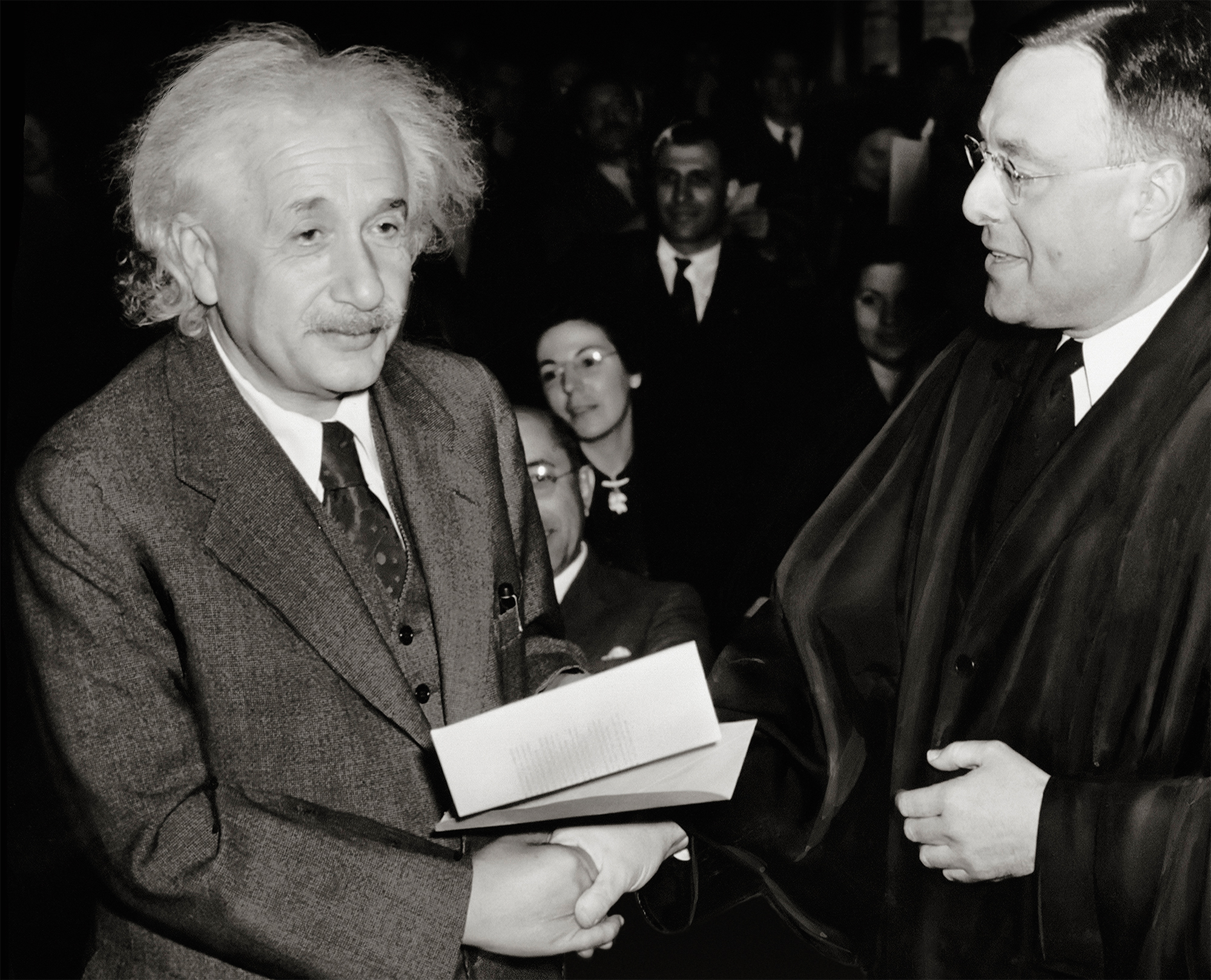

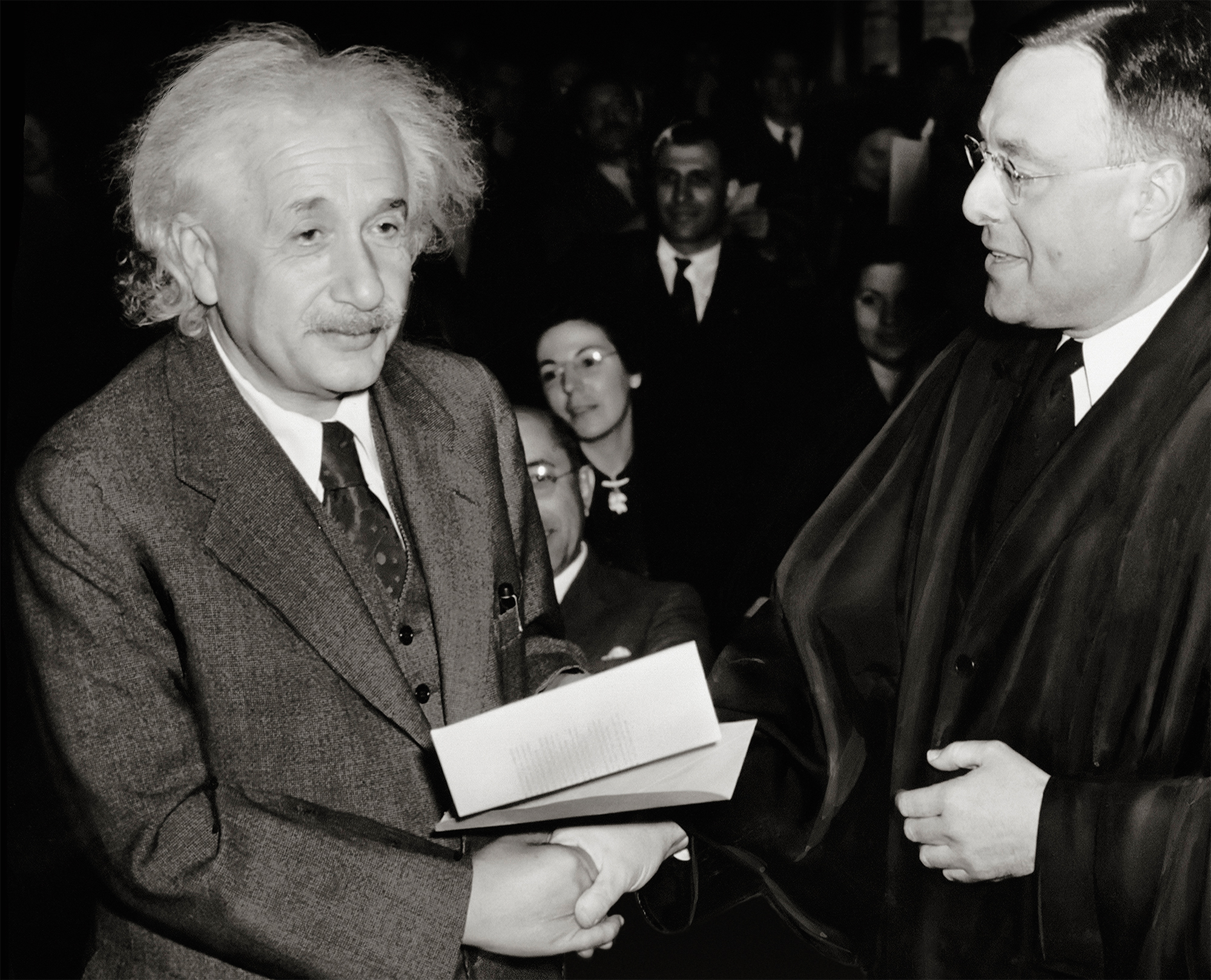

German was not to hold its prominent position for long. After World War I, researchers from the U.S., England, France, and Belgium formed major scientific organizations, such as the International Astronomical Union. Unwilling to embrace their former foes, they left German scientists out. Germany suffered another setback in 1933, when the government dismissed one fifth of the nation’s physics faculty and one eighth of its biology professors for cultural and political reasons (Jews and socialists were banned). Many left the country for the U.S. and England, where they started publishing in English.

Though the trend from that point on was toward English as the universal language of science, the shift took decades. One roadblock was the Cold War. During the 1950s and ’60s, most scientific literature was published in either English or Russian. “Then in the 1970s, everything turns,” Gordin says. As the Soviet Union fell into decline, the use of Russian declined too. By the mid-1990s, about 96 percent of the world’s scientific articles were written in English, a trend that has only grown since. These days, he says, “publishing in English is almost not a choice.”

Have a burning science question you’d like to see answered in our FYI section? Email it to fyi@popsci.com.

_This article originally appeared in the November 2013 issue of _Popular Science.