THE NATURAL WORLD is not always a calm place. Every day, animals from the ocean floor to the highest treetops struggle to live, breed, and eat. Their existential endeavors make many of our modern stressors seem placid by comparison. But we still seek out signs of serenity in the wild—and if we press the camera shutter at precisely the right moment, we might just find them.

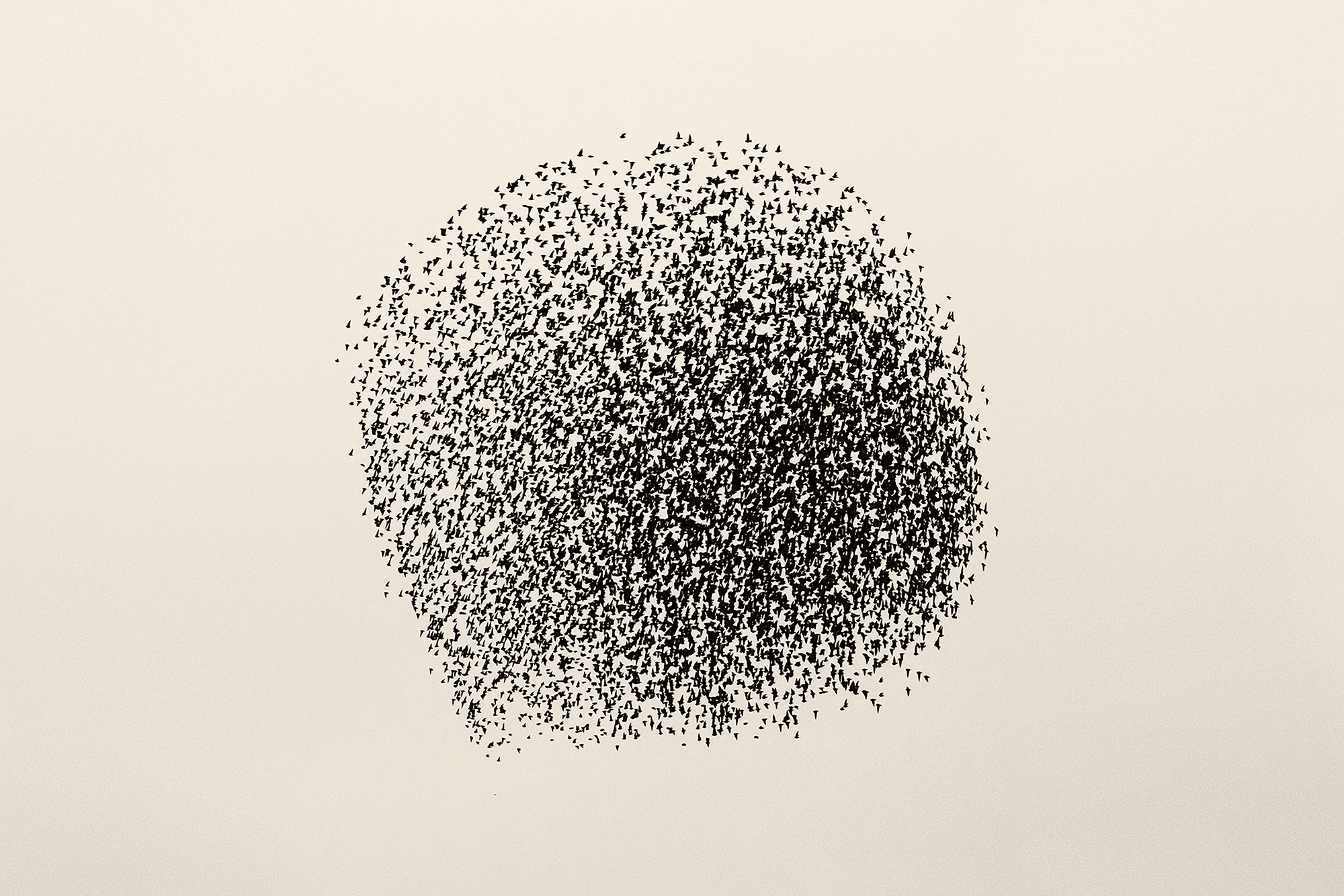

These images capture flocking birds and schooling fish suspended in smooth, synchronized swirls—twin phenomena of the sky and sea. But while they seem to have complex choreography from behind a lens, avian and aquatic dances follow just one simple rule: If your neighbor makes a move, you follow suit. In both cases, this rote locomotion results in a comforting cluster better able to protect the animals from predation. It also has the potential to produce infinite shapes in the water and air, providing us onlookers with endlessly satisfying displays.

Lots of bird species form flocks, but Sturnus vulgaris—the common starling, native to Eurasia but found on every continent save Antarctica—indulges in unusually frequent and lengthy get-togethers known as murmurations.

Fish like these sardines in the Philippines use all their senses to feel out the distance between themselves and their compatriots, which allows them to maintain consistent and precise gaps.

Starlings use their keen peripheral vision to track neighbors’ movements. Research suggests they form murmurations primarily as a means of protection from predators they encounter on their journey down to roost.

These Caranx sexfasciatus in Indonesia are beginning to form a circular school. This common shape minimizes the fraction of the group left exposed to the outer ocean—and the hungry threats that lurk there.

While individual sardines measure just 6 to 12 inches long, groups of them can collectively stretch out for miles. Aircraft can often spot their wriggling schools from the sky.

Starlings tend to murmurate a bit longer when it’s cold, suggesting they find warmth in numbers. But they flock the longest when an aggressor is actively circling.

This story originally ran in the Spring 2021 Calm issue of PopSci. Read more PopSci+ stories.