We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

One of Google’s stated goals is to index all of the world’s information, the ever-changing mass of combined knowledge and snarky commentary that lives on the Internet. Today this index is getting some context, with billions of attributes and connections linking millions of individual nouns — Things, in Google’s parlance. This type of context-informed dataset is frequently known as the semantic web, but Google is avoiding that term and calling it Knowledge Graph.

Human conversation is built on context, explained Jack Menzel, product management director of search at Google. But for a computer, it doesn’t exist. Ask a person about “Kings” and the response will probably be another question, to put your query in context. Are you talking about the L.A. Kings? Or playing cards? Or a TV show? Google’s new search algorithm seeks to disambiguate your results, much like a person would in a conversation, Menzel said.

“Understanding is part of being a human. For computers, it would be like if we suddenly pick a language that neither of us can speak. It’s just a collection of sounds,” he said. “What search engines have lacked so far, until today, was the notion that those words refer to a thing. If we maintain a representation of a thing, we can use that to better understand both what you are asking for and what the web itself is talking about.”

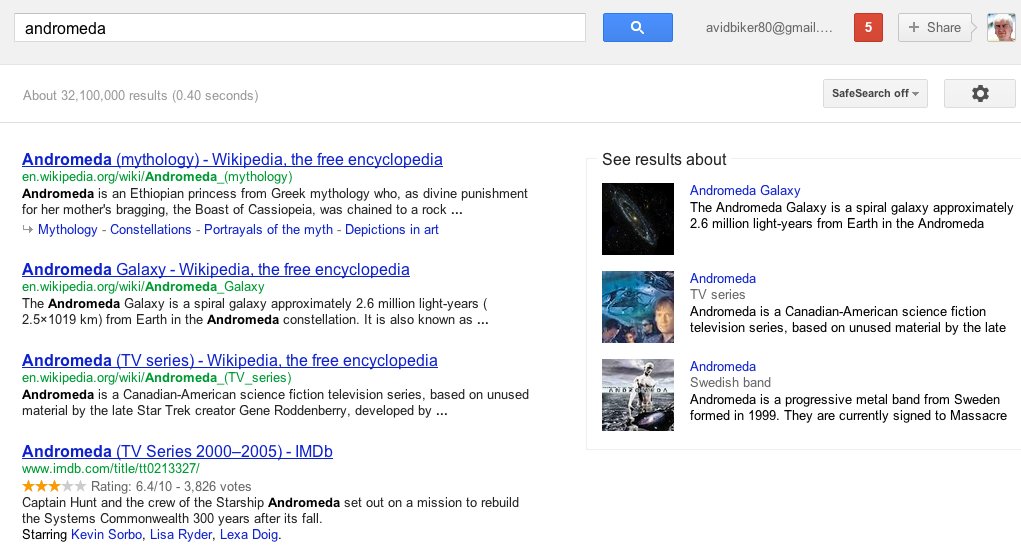

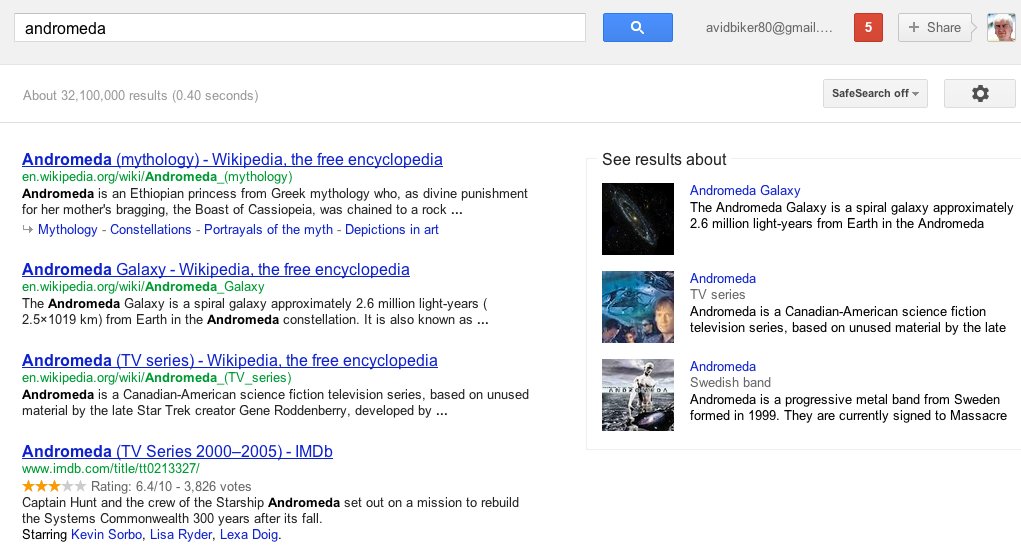

If you’re logged into Google, you may be seeing this new function already — it started rolling out May 16 and will be complete for all logged-in English language users by the 18th. Type in a search term, and instead of listing what you might interested in, the search will provide you a set of options. Menzel uses “Andromeda” as another example. You could choose between the galaxy, the Greek myth, the Swedish metal band, and so on.

To do this, Google set about indexing universal definitions, using every public database from Wikipedia to the CIA World Factbook to Google’s own products. The result is a new set of 500 million people, places and things, with 3.5 billion connections among them. Along with allowing you to narrow your context, search results now contain little connections and suggestions to augment an initial search term.

People search results come with biographical information, for instance; places results come with data about the place; and so on. Search for Frank Lloyd Wright, and you’ll see a Wikipedia-based summary of him, a biographical sketch, and a Google-curated list of houses he designed, which will take you to further information if you click.

Definitions of things are inherently contextual — whether your first definition of Kings is a hockey team, a basketball team, a TV show or a gang depends on who you are and where you are. Google will also make some determinations based on your search profile and especially your location, Menzel said. He used an example of place near Google’s Mountain View, Calif. offices — when he searches “Great Bear,” Google brings up a northern California recreation area and a coffee shop in Santa Cruz. In your location, it will probably bring up something else. But personalization is still incomplete, he said.

The ultimate goal is a smarter search that thinks like a person would, taking your individuality and context into account. It’s not just about knowing that a thing is a thing, Menzel said — “it’s what’s important about that thing, what’s relatable about that thing. and the connections about that thing. How can we take this understanding of the world, and make it so we can improve your information?”