We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

Schizophrenia can present itself with any number of symptoms, from disorganized thinking or motor behavior, to hallucinations or delusions. Together these manifestations often leave a patient unable to function normally and with very few effective treatment options. And though researchers had not been able to figure out the underlying cause of the disease, they’ve learned a lot in the past few years—genetic mutations probably play a role, as does the immune system and the microbiome. Now scientists have identified a genetic variant in schizophrenic patients that links many of these previous observations, according to a study published today in Nature. If the researchers have in fact discovered the underlying biological cause for schizophrenia as they claim, it could lead to better treatments for the condition.

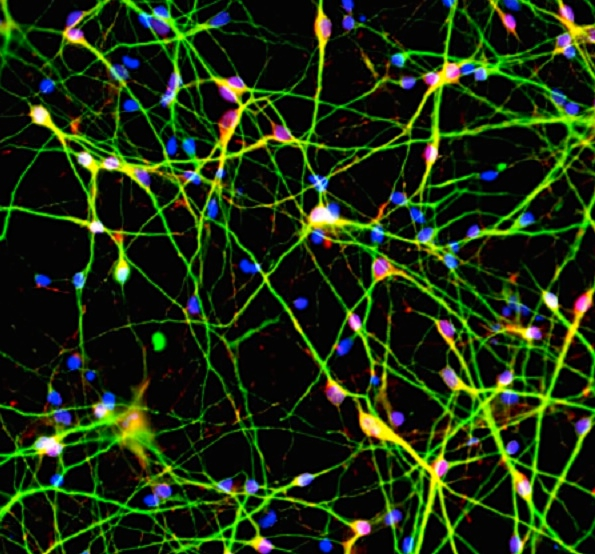

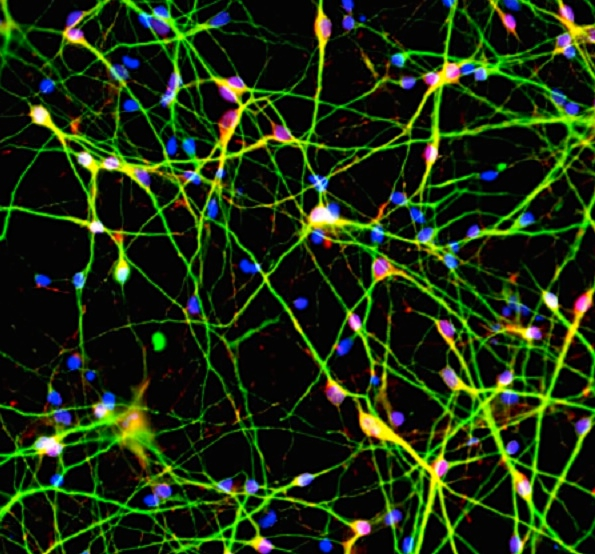

Over the past five years, the researchers have collected genetic data from 65,000 people in 30 countries. They knew that mutations in certain genes were linked to schizophrenia, but the researchers wanted to use their huge dataset to find the strongest correlation possible. And they found one—people with highly expressed variations of a gene called complement component 4 (C4) were much more likely to develop schizophrenia. They confirmed the connection between C4 genes and protein production by analyzing 700 samples of human brains.

Scientists already knew that the C4 gene generates a protein that the body uses to mark pathogens so that the immune system destroys them. But, importantly, it’s also used during synaptic pruning, a period in adolescence in which the brain eliminates excess connections in order to strengthen the pathways it uses most often. Through experiments in animal models, the researchers found that greater C4 expression leads to more synaptic pruning.

These C4 variants could lead to excessive synaptic pruning during adolescence, the researchers believe, which could make a patient more likely to develop schizophrenia. That might explain why schizophrenia symptoms start in the teens or early 20s, and why adults with schizophrenia have thinner cerebral cortices that contain fewer synapses. C4 also likely affects the immune system and the components of the microbiome in schizophrenic patients, though the exact relationship between C4 expression and immune variations is still unknown.

Understanding the biological mechanism means that researchers could develop more effective treatments for schizophrenia, as the ones currently in use are largely designed to manage symptoms but not address the disease directly. If scientists could decrease the synaptic pruning during a patient’s adolescence, they might be able to reduce the severity of schizophrenia, or maybe prevent the disease altogether.

“This study marks a crucial turning point in the fight against mental illness,” Bruce Cuthbert, the acting director of the National Institute of Mental Health and who was not involved in the research, said in a press release. “This study changes the game. Thanks to this genetic breakthrough we can finally see the potential for clinical tests, early detection, new treatments, and even prevention.”