Identifying animals in photos is trickier than you might think

Images that supposedly showed the extinct thylacine were actually of a pademelon. But how could you even confuse the two?

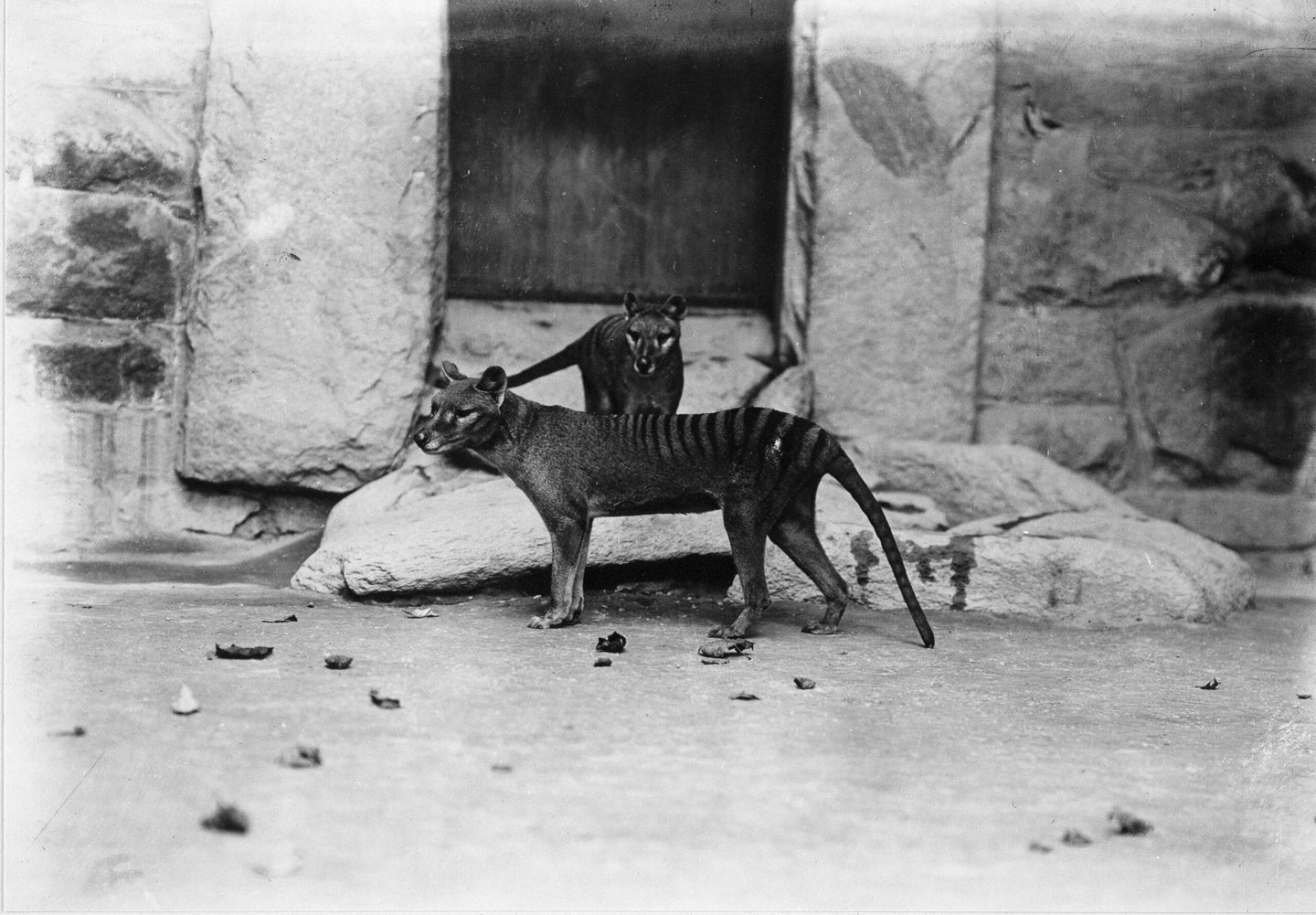

After a week of fanfare, an Australian man released photos of what he believes to be a Tasmanian tiger, also known as a thylacine, a six-foot long marsupial carnivore that white settlers hunted to extinction in the early 1900s. The photographer, Neil Waters, is the president of Tasmania’s Thylacine Awareness Group, which searches for evidence of the creature.

To be clear, Tasmania’s go-to authority on tiger identification, a curator of vertebrate zoology named Nick Mooney, does not believe that the photos show thylacine. “Based on the physical characteristics shown in the photos … the animals are mostly likely Tasmanian pademelons,” a sort of round-bottomed wallaby, according to a statement from the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, where Mooney works. (Other zoologists have agreed.)

But the photos are surprisingly ambiguous given how distinct the two animals are. One image looks like a wallaby hopping away from the camera. Another has shows a cat-like animal, with short, pointed ears. But the third? It’s harder to recognize, and there’s a hint of the stiff tail and stripes that distinguished the thylacine.

That’s the image Waters hangs his assertion on. He believes that it’s a baby, trotting away from the camera. “It’s got the shaggy hair I’ve seen on the juveniles in the Adelaide Museum,” he says. “It has got rather shiny, smooth hocks.” This, he says, would have to be a very strange-looking kitten.

So far, the expert consensus is firmly that these are not thylacines. But it raises a question: how could there be contention over a photo taken in broad daylight? And more to the point, is it really reasonable to think that an animal like a thylacine could live under the noses of humans all this time? As it turns out, people are asking the same question about animals in the United States. And it’s harder to be sure than you might think.

Grizzly bears in the Colorado Rockies?

David Petersen, the author of Ghost Grizzlies, says he’s seen something like the furor over the tiger before. He spent years interviewing people who’d claimed to have seen grizzly bears in the Colorado Rockies, where they had supposedly been extinct since 1979.

“It was just a constant flood every summer of people reporting grizzly bears,” he says. It was obvious to him that those were cases of mistaken identity, and said more about people than bears. “I evolved this theory that we kill off the real monsters, the animals that threaten us, and then in our imaginations we are driven to recreate them.”

It’s easy for a casual observer to mix up a grizzly and a black bear, which still live in Colorado, Petersen says, because western black bears are often brown, and grow much larger than people expect. The telltale signs are the grizzly’s humped back and flat face, and the black bear’s long, upright ears, but they can be subtle differences to the untrained eye.

A definitive judgment, he says, would involve both a photo in a readily identifiable place, and some poop or fur for genetic testing.

But even visual evidence can be tricky. Petersen says that he liked to show audiences a photo that had supposedly been taken in southern Colorado. “I would challenge people with this photo—is this a grizzly bear, or is it a black bear? And people were about 50-50 split on it, including so-called experts.” (He later decided that the photo didn’t come from Colorado and stopped using it.)

He doesn’t believe that grizzlies survived in Colorado, although it’s plausible that a few may travel down from Wyoming. And he’s only become firmer in that belief over time. “When I was doing my research in the early and mid 90s,” he says, “there were no trail cameras. Now there are millions of those things out there. Someone would have gotten it on camera by now.”

But, he says, whether or not an animal—even a huge one, like a grizzly—can be found is a very different question from whether people want to find it, and that’s led to ambiguities before. In the ’50s, the Colorado government declared the bear extinct, in spite of credible sightings from trappers. “At the same time, they had hired a guy to go up there and prowl around, secretly, to see if he could find more evidence.”

Over the following decades, he says, different state governments were more or less warm to the possibility of grizzlies based on political ties to ranching. “There’s all kinds of subtle political and psychological stuff going on in that world.”

In the end, Petersen defers to a “grizzly guru” who he interviewed for his book. “I don’t think there are any in Colorado, but it would be arrogant of me to proclaim that there aren’t, because we can’t know that.”

Ivory-billed woodpeckers in Arkansas?

And not so long ago, biologists believed that they’d rediscovered a large, loud, lost animal in the United States.

The ivory-billed woodpecker, a supersized cousin of the pileated woodpecker, lived in the swamps and pine forests of the Southeast until habitat loss drove it under in the mid 1900s. The last universally accepted sighting was in 1944 in a stand of old-growth forest in northeast Louisiana, just before the stand was was logged. But plausible sightings have continued ever since. There have been feathers, (age-unknown), (too-blurry-to-be-definitive) videos, and recordings of their distinctive (but not-distinctive-enough) call.

In 2005, some of those accounts, based on surveys conducted in the swampy bottomlands of Arkansas, were published in the journal Science, leading to a flurry of interest.

The researchers described the discovery in awe: “It’s like a funeral shroud has been pulled back, giving us a glimpse of a living bird, rising Lazarus-like from the grave,” one told the Cornell Chronicle in 2005. Another told New Orleans radio station WWNO in 2017 that the bird looks “almost like a mythical creature.”

The catch is that those findings are disputed by other ornithologists, and there haven’t been any sightings by other teams for more than a decade. All the same, tens of thousands of acres have been protected on the bird’s behalf.

Gray wolves in the Washington Cascades?

Just an hour and a half from downtown Seattle, biologists are asking similar questions about the range of gray wolves, which were extirpated in the 1930s, but have slowly rebuilt their numbers by moving in from Canada.

For the moment, most of those wolf packs are concentrated in the remote northeastern corner of the state, where they often come into conflict with ranchers. Prime wolf habitat in the protected areas around Mount Rainier and Olympic National Park, far to the west, so far remains empty. In between the two is I-90, a major barrier to animal movement.

“We’re expecting wolves to repopulate the southern Washington Cascades,” says David Moskowitz, a conservation biologist and photojournalist, who spearheads a volunteer effort to gather evidence of wolves south of the freeway with a nonprofit called Conservation Northwest.

There have been credible sightings of wolves in that area, he says, but definitive evidence is hard to come by. “Just because you get a photo of a wolf-like creature on your camera doesn’t mean you have wolves back in that area,” he says. Ruling out a coyote or a wolf-dog can be impossible from a photograph, and so the exact range of wolves remains unknown..

But there are major differences between wolf dispersal and a thylacine, Moskowitz cautions. “It’s hard to detect a single wolf, but if there’s a breeding population, you’re going to have localized activity, lots of coming and going.”

Eventually, he says, “it becomes increasingly hard for the creature to go undetected.” Asked what he thinks the likelihood of a pack going undiscovered in the region he surveys, he says, “I think it’s probably safe to say there’s not a breeding population of wolves south of I-90. Could a pair of wolves have had a litter of pups at some point in the last 10 years? Sure. Has it been a long-term, stable thing? That’s a lot harder to imagine.”

And for thylacines, living and breeding for decades undetected? “That’s hard to fathom.”

But, like Petersen, Moskowitz says that the question itself is a product of cultural forces. Out on the Olympic peninsula, which is covered in heavy forest and sharp mountains, there’s been conjecture for years that wolves are still around.

That came to a boil in the 1990s, Moskowitz remembers, when the state was discussing reintroducing wolves to the area. “That led to conspiracy theories, [people saying], the wolves are already here.” And if the wolves were there, it stood to reason that there was no need to reintroduce them.

And that motivated reason can muddy the process of gathering evidence. In Tasmania, where the killing of the thylacine went hand-in-hand with a state-sponsored genocide of indigenous Australians, he suspects, “If you have folks from that culture that extirpated that species and those people, there’s this idea of redemption.”